Cowardice asks the question, ‘is it safe?’; expediency asks the question, ‘is it politic?’; vanity asks the question, ‘is it popular?’; but conscience asks the question, ‘is it right?’; and there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular, but because conscience tells one it is right.

– Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968)

Baptist minister and leader of the American civil rights movement

Q. Legality of a medical act per Sec 2(14) and 2(15) of BNS is challengeable under provisions of Sec 26 BNS, and the medical ethics. Then why not the legality of a surgeon’s act of terminating the life of a viable fetus in the advanced stage of pregnancy?

It may be medically legal for terminating the pregnancy when its continuation threatens the life of the mother, but not otherwise. MTP up to 24 weeks pregnancy may be legal under MTP Act but certainly not ethical for a physician, except when it threatens the life of the mother. Besides, how is his act of invading the body of a live child with intention to kill, in conformity with BNS 26 which stipulates that a medical act to be legally valid should have been done in good faith, with his consent and for his benefit?

AI: Under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), every bodily injury is “illegal” if it’s an act one is not “legally bound to do” (Sec 2(14)), and only acts done in “good faith” (i.e. with due care and attention) are protected (Sec 2(15)). Section 26 then carves out a narrow exception:

Three things must coincide for Sec 26-protection:

- The beneficiary of the act gives informed consent.

- The actor has no intent to kill.

- The act is done in good faith for the beneficiary’s own benefit.

A late-stage abortion of a viable fetus in the absence of maternal risk fails all three:

- The fetus is not a legal “person” capable of consent (and no doctrine of implied fetal consent exists).

- The procedure intends to kill the fetus rather than to heal it.

- While the mother consents to protect her own health or autonomy, that consent doesn’t equate to the fetus’s consent under Sec 26.

Moreover, the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 (MTP Act) is a special statute that expressly immunizes registered medical practitioners from criminal liability under the IPC (or any other law, including BNS) so long as they follow its conditions (Sec 3). The MTP Act permits abortion:

- Up to 20 weeks on specified grounds (maternal life/health risk, rape, fetal anomaly, contraceptive failure in minors or married women)

- Up to 24 weeks for select categories, always subject to medical–opinion safeguards.

Beyond those limits, termination is strictly unlawful, and a physician performing it could face prosecution for homicide or negligence under BNS (e.g., Sec 106) or the IPC.

Ethically, the physician’s primary duties—beneficence, non-maleficence and respect for autonomy—justify abortion only when it averts a greater harm (e.g., maternal death or serious morbidity). Performing a non-therapeutic, late-term abortion of a viable fetus, outside the narrow MTP grounds, contradicts both the ethical principle of doing no greater harm and the legal scheme of BNS Sec 26.

In short:

- BNS Sec 26 cannot shield a procedure whose primary aim is fetal death and where the direct “beneficiary” (the fetus) cannot consent.

- MTP Act immunity only applies within its gestational and medical bounds.

- Ethically, terminating a viable fetus absent maternal risk breaches core medical-ethical principles.

— You might also be interested in how different jurisdictions define fetal “personhood,” recent jurisprudence on viability and maternal autonomy, or the interplay between disability-rights law and fetal anomaly grounds under the MTP Act.

Q. Is it not legal for a physician to refuse to do a non-therapeutic abortion? Can he be compelled to do it?

AI: Under Indian law a physician’s duty to perform abortion is strictly limited—and no one can be forced to do a non-therapeutic termination against her will. In fact:

- The MTP Act is a permissive statute, not a command. It says when and by whom an abortion may be done; it does not impose a duty on every registered medical practitioner to provide the service.

- A doctor who honestly believes a request falls outside the Act’s conditions (e.g., exceeds gestational limits, lacks requisite medical opinion or consent) must refuse—it would be a criminal offence for her to do so.

- Even when a case technically falls within the MTP Act, there is no provision that compels a conscientious or clinical refusalist to proceed. Unlike some jurisdictions (where “conscience clauses” are written in), Indian law is silent on conscience, but it never overrides a physician’s professional autonomy.

- In practice, a practitioner who declines must still ensure the patient can access a willing colleague or centre.

- There is likewise no power—statutory or judicial—to coerce a doctor into performing a non-therapeutic abortion. Courts will not “order” a physician to kill a fetus any more than they could command surgery without consent.

If the jurisdiction believes too few providers are available, the policy remedy is to widen training and accreditation—not to tie doctors to operating tables.

In short, non-therapeutic abortion lies entirely in the physician’s clinical and moral discretion, constrained only by the MTP Act’s eligibility criteria. Neither statute nor court can force a practitioner to violate her professional judgment.

Q. As regards therapeutic abortion…

That is when the continuation of pregnancy is medically found to have become a threat to the life of the mother, the mother has an absolute right to demand termination of pregnancy, and her right casts a legal obligation on the gynecologist to do it. Dehors of threat to her life, a mother may have a right to non-therapeutic abortion under the MTP Act, but her right in this case does not cast any corresponding duty on the gynecologist to do it. The act of gynecologist would not be legal under the BNS 26. A physician has ethical duty and right to refuse to kill the child to terminate the pregnancy. Please elaborate the legal position.

Legal Framework for Abortion in India

Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971

The MTP Act provides two broad categories under which abortion is permitted:

- Therapeutic abortion: When continuation of pregnancy poses a risk to a woman’s life or could cause grave injury to her physical or mental health.

- Non-therapeutic abortion: On grounds such as rape, contraceptive failure, change in marital status (e.g., widowhood or divorce), or substantial fetal abnormalities.

The Act originally allowed termination up to 20 weeks of gestation:

- Up to 12 weeks on the opinion of one Registered Medical Practitioner (RMP).

- Between 12 and 20 weeks on the opinion of two RMPs.

The 2021 Amendment extended the upper limit to 24 weeks for specified “vulnerable” categories (rape survivors, minors, differently-abled women, etc.) and permits termination beyond 24 weeks if a Medical Board certifies substantial fetal abnormalities.

Physician’s Legal Duty vs. Discretion

Therapeutic abortion: A pregnant woman has an absolute right to demand termination when her life is at stake. In such cases:

- The MTP Act imposes a legal obligation on a qualified gynecologist or RMP to perform the procedure.

- Doctors acting in accordance with the Act are expressly exempted from prosecution for what would otherwise be an offence under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) Section 88 (formerly IPC Section 312).

Non-therapeutic abortion:

- The woman retains a statutory right to seek termination under the MTP Act.

- This right does not translate into a legal duty on the physician to perform it.

- A gynecologist may lawfully refuse, and such refusal cannot be equated with violating the woman’s rights or professional misconduct under the Act.

Criminal Liability Under Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Section 26

Section 26 of the BNS protects only those acts that are:

- Not intended to cause death.

- Done in good faith for the benefit of the person who consents (expressly or impliedly).

- Where the doer neither intends nor knows they are likely to cause death.

Illustration: “A surgeon, knowing an operation may cause death but not intending it, and acting in good faith for the patient’s benefit with consent, commits no offence.”

In contrast, a non-therapeutic abortion outside the MTP Act’s prescribed grounds would:

- Lack the “good faith” justification recognized by Section 26.

- Expose the physician to prosecution for causing miscarriage (up to seven years’ imprisonment) under BNS provisions replacing IPC Sections 312–316.

Ethical Rights and Professional Conscience

Medical ethics and professional codes acknowledge:

- A physician’s primary duty to preserve life and relieve suffering.

- A qualified doctor’s right to conscientious objection when a requested intervention (e.g., elective abortion) conflicts with deeply held moral or religious beliefs.

However, ethical guidelines typically require objecting physicians to:

- Inform the patient promptly of their refusal.

- Refer the patient to another qualified provider without undue delay.

Summary of Legal Position

- Therapeutic Abortion:

- Absolute right of the woman if her life is at risk.

- Physician has a corresponding duty to perform; protected from criminal liability.

- Non-Therapeutic Abortion:

- Woman retains a right to seek termination under the MTP Act.

- Physician has no enforceable duty; may refuse on legal or ethical grounds.

- Criminal Safeguards:

- BNS Section 26 shields only bona fide, consented acts for a person’s benefit, not elective abortions outside statutory grounds.

- Ethical Refusal:

- Physicians can invoke conscientious objection but must ensure patient access by suitable referral.

This dual structure balances a woman’s reproductive rights with a physician’s legal protections and ethical autonomy.

Abortion Beyond 24 Weeks: Navigating the Gynecologist’s Legal Duties

When pregnancy exceeds the 24-week ceiling under the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, only a High Court or Supreme Court order can lawfully authorize termination. These judicial orders operate under Articles 226 and 142 of the Constitution to “fill gaps” in the statute and shield a woman—and her treating doctor—from prosecution under Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) Section 88 (which mirrors IPC Section 312).

- Judicial Orders as Legal Foundation

- Under the MTP Act, no termination is permitted beyond 24 weeks except for fetal abnormalities certified by a State-level Medical Board (Rule 3B).

- Courts have used their extraordinary powers to permit late-term abortions on constitutional grounds (right to life and dignity under Article 21).

- A valid High Court/Supreme Court order transforms the procedure into one “immediately necessary,” thereby invoking BNS Section 88’s “consent + good faith” exemption.

- Exemption from Criminal Liability (BNS 88) BNS Section 88 provides that an act done in good faith for the benefit of the consenting person is not an offence, even if it causes death. Under a court order:

- The doctor’s “good faith” is established by the judicial sanction.

- The woman’s consent meets the statutory requirement.

- The act is thus immunized from charges under Sections 312–316 (formerly IPC) for causing miscarriage.

- Fetus vs. Live-Born Child: Personhood and Homicide Risk

- Indian criminal law treats a fetus (pre-birth) differently from a born child. Until live birth, there is no “person” entitled to the right to life.

- If, during a late-term termination, the child is accidentally born alive and then killed, that act constitutes homicide (BNS Sections 300–302).

- The gynecologist must therefore ensure that no live child emerges from the procedure—or, if one does, that the child is afforded immediate medical care.

- Safeguarding Against Live Birth: Feticide Protocols To eliminate the risk of a live birth—and consequent homicide exposure—practitioners routinely:

- Administer intra-fetal feticide (e.g., KCl or digoxin injection) under ultrasound guidance to induce fetal asystole.

- Confirm fetal demise ultrasonographically before commencing evacuation.

- Document both steps meticulously in the medical record.

- Ethical and Professional Duties

- Verify the court order explicitly covers the patient’s specific gestational age and circumstances.

- Obtain informed consent from the woman (and guardian if minor/mentally ill), as per MTP Act Form C.

- If, contrary to plan, a live child is born, provide emergency neonatal care and arrange for transfer/adoption—killing or abandoning a live infant is impermissible.

- Respect conscientious objection rules: objecting doctors must refer promptly to a willing provider.

Key Takeaway

By combining a valid High Court/Supreme Court order, strict adherence to BNS Section 88 criteria, and a two-step feticide-plus-evacuation protocol, gynecologists can lawfully terminate pregnancies beyond 24 weeks while avoiding the gravest criminal risks—even those arising from an unintended live birth.

Why Supreme Court’s “Carry-to-Term” Directions Remain Case-Specific, Not a General Rule

1. Courts vs. Legislature: Limits of Judicial Rule-Making

The Supreme Court’s power under Articles 32/226 is to offer extraordinary, fact-specific relief—never to legislate wholesale policy. When it ordered a rape survivor to carry her pregnancy to term and directed the State to bear costs and ensure child care, it did so by balancing her unique delays and neglect, not by rewriting medical law for every refusal.

2. Every MTP Objection Has Different Stakes

Key factors vary wildly:

- Gestational age (early vs. late stage)

- Medical necessity (risk to life, fetal anomalies)

- Mental-health impact

- Systemic delays or negligence

In the Bihar survivor’s case, protracted judicial and bureaucratic holdups pushed her past the 24-week limit. The Court’s remedy—state-funded child care and compensation—was tailored to those exceptional facts, not a template for all abortion refusals.

3. Balancing Doctors’ Conscience with Women’s Autonomy

Under global medical-ethics norms (and echoed by India’s Medical Council guidelines), physicians may conscientiously object but must immediately refer patients to willing providers. Converting one Supreme Court order into a blanket “rule” would invert that balance—undermining women’s constitutionally protected privacy and bodily autonomy under Article 21, and risking forced continuance in situations where termination is legally permitted.

4. Practical and Policy Constraints

Mandating state-sponsored care for every MTP refusal would:

- Strain public health budgets

- Create complex child-welfare logistics

- Deter hospitals from offering MTP services

A more sustainable route is strengthening the MTP Act’s referral framework—ensuring every woman denied locally is swiftly linked to an authorized centre.

5. A Legislative Path Forward

Rather than rely on exceptional Supreme Court dicta, Parliament could amend the MTP Act or Rules to:

- Codify doctors’ referral obligations with strict time-frames

- Institute monitoring of every conscientious-objection notice

- Create a dedicated fund or scheme for children born when abortions are denied through no fault of the mother

Such an approach embeds predictability, preserves women’s rights, respects medical conscience, and relieves courts from crafting bespoke relief in each case.

Q. It is not a case of ‘forced continuance in situations where termination is legally permitted’ but a case where it is not legally permitted per MTP Act or IPC 312.

Why the Supreme Court’s “Carry-to-Term” Order Stays an Exceptional Remedy

- Statutory Frame: Beyond 24 Weeks, MTP Is Illegal The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act caps legal terminations at 24 weeks (with narrow judicial extensions only for fetal anomalies). Once a pregnancy crosses that threshold, any abortion—even with the woman’s consent—runs afoul of both the MTP Act and Section 312 of the IPC. In the Bihar case, the gynecologist’s refusal wasn’t conscience-based but simply compliance with the statute’s absolute cutoff.

- Extraordinary Jurisdiction Under Article 32 The Supreme Court’s power under Article 32 isn’t legislative. It can craft bespoke relief when fundamental rights (here, life, liberty, dignity) collide with administrative breakdowns—especially where repeated judicial and bureaucratic delays pushed the woman past 24 weeks. That constellation of failure and urgency justified a unique “carry-to-term plus state support” remedy, not a general rule for every doctor’s refusal.

- Why One-Size-Fits-All Would Backfire

- Resource strain: Mandating state-funded care for every refused case would overwhelm public health and child-welfare systems.

- Disincentive effect: Hospitals might shrink MTP services to avoid potential downstream obligations.

- Judicial overreach: Turning this bespoke relief into routine protocol would substitute legislative policymaking with case law.

- Preserving Balance: Women’s Rights vs. Medical Conscience Doctors already have a limited right to conscientiously object—but the law requires immediate referral to another provider. If carrying to term plus state care became the default whenever a doctor declines, that would effectively penalize women denied legally permissible abortions (in other contexts) and erode the referral imperative.

- Making It a Predictable Safeguard—Legislative Pathways To move from exception to a reliable safety net without judicial micromanagement, Parliament could:

- Amend the MTP Act to codify swift referral deadlines (e.g., 24–48 hours).

- Establish a central “MTP Facilitation Fund” covering travel, treatment, and—where refusal pushes a woman beyond 24 weeks—childcare until adoption or guardianship.

- Mandate real-time tracking of refusal notices and automatic escalation to district health authorities.

When Law Ends, Ethics Begins: The Gynaecologist’s Right to Decline.

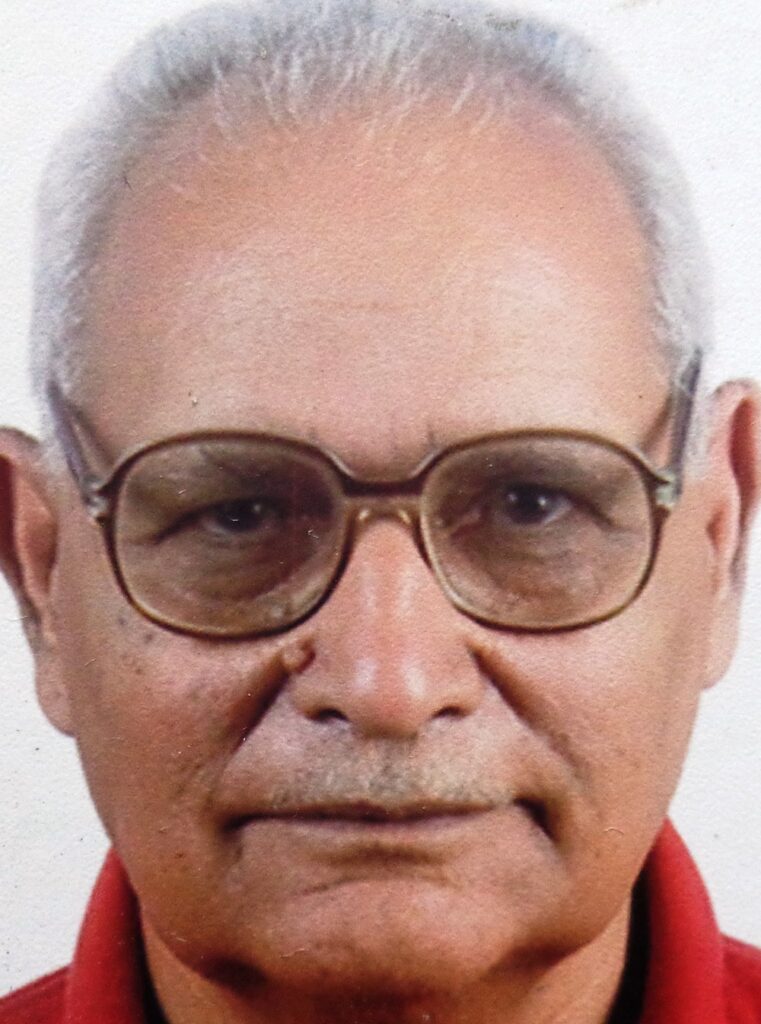

Written By: Dr. Shri Gopal Kabra, MBBS, LLB, MSc, MS(Anatomy), MS(Surgery)

Email: [email protected]