White Coats, Grey Zones: The Judicial Strain Between Healing Intent and Illegality

The article underscores the classic legal dilemma between wrongful harm and privileged action under statutory license.Introduction:

Injury, as traditionally conceived in law, is an actionable wrong arising from the unlawful invasion of a legally protected interest. But what happens when harm results not from an unlawful act, but from a procedure performed under statutory license—by a medical professional acting with purported “beneficial intent”?

Section 26 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita introduces precisely this conundrum: it accords legitimacy to acts done in “good faith” for a person’s benefit, potentially shielding the actor from criminal liability.

Relevant Provisions from BNS:

- Section 2(14) – Injury: “Injury” means any harm whatever illegally caused to any person, in body, mind, reputation or property.

- Section 2(15) – Illegal and Legally Bound to Do: The word “illegal” is applicable to everything which is an offence or which is prohibited by law, or which furnishes ground for a civil action; and a person is said to be “legally bound to do” whatever it is illegal in him to omit.

Legal Query:

Will you please analyse the above two provisions in the context of medical negligence alleged to have been committed by a duly registered and licensed medical practitioner?

Under the common law doctrine of ‘duty of care’, a licensed medical practitioner is duty-bound to provide treatment when approached by a patient.

Can the act of such a doctor be considered illegal?

Can the harm, intentional or unintentional, caused by a ‘legal’ act of the physician be considered injury for liability?

AI: Let’s break down the analysis of these provisions and their implications for a licensed doctor accused of medical negligence.

-

Definitions and Their Implications

BNS 2(14) – “Injury”: This provision defines “injury” broadly as any harm—whether to the body, mind, reputation, or property—that is illegally caused. For harm to qualify as “injury,” its cause must involve an element of illegality.

BNS 2(15) – “Illegal” and “Legally Bound to Do”: This defines “illegal” as any act or omission that violates the law. A person is legally bound to act when there’s a duty imposed by law. Therefore, failure to act where required by law may be deemed illegal.

-

The Duty of Care and Its Legal Consequences

Under the common law doctrine of duty of care, a licensed doctor is legally obligated to provide treatment when approached by a patient. This means:

- Duty to Act: A registered doctor must provide care, especially in urgent situations.

- Omission as a Violation: Failing to treat a patient when treatment is indicated can be seen as an “illegal” omission under BNS 2(15).

If harm results from such neglect, it may qualify as “injury” under BNS 2(14), since it stems from an illegal omission or a gross deviation from accepted standards.

-

When Is the Doctor’s Act Considered "Illegal"?

Legal Acts vs. Illegal Acts in Medical Practice:

- Legal, Standard Practice: A properly performed treatment using accepted methods remains “legal,” even if complications arise. The resulting harm is considered an accepted risk and not an “injury” under BNS 2(14).

- Deviation from Duty (Negligence): If a doctor fails to act when required, or acts incompetently, and harm results, then the act or omission becomes “illegal” under BNS 2(15). The foreseeability and direct connection to the breach make it compensable as an “injury.”

Thus, a doctor’s act becomes “illegal” only if it deviates from the legally required standard of care.

-

Injury from a "Legal" Act: When Does It Become Liable?

Under BNS 2(14), “injury” must be illegally caused. This creates two scenarios for a physician:

- Lawful Acts with Known Risks: If a treatment is legally and carefully performed, resulting complications—even severe ones—are inherent risks. No liability arises as the act isn’t “illegally caused.”

- Negligent Acts or Omissions: If a doctor fails in their duty or performs an erroneous procedure, the resulting harm is from an “illegal” act, and qualifies as “injury” under BNS 2(14), regardless of intent.

Therefore, liability depends not merely on harm but on whether the harm was caused by a breach of legal duty.

-

Synthesis and Broader Considerations

Q: Can a doctor’s act be considered illegal?

A licensed doctor’s act isn’t inherently illegal just because they treat a patient. It becomes illegal if the doctor:- Fails to treat when legally obligated (illegal omission), or

- Performs a procedure that significantly deviates from accepted practice, breaching the duty of care.

Q: Can harm caused by a “legal” act be considered injury for liability?

If the doctor follows the standard of care, any harm—even if unintended—does not attract liability under BNS 2(14). But if the legal act is performed negligently and causes harm, it may qualify as “injury.”These distinctions highlight the balance in medico-legal jurisprudence: holding doctors accountable for negligent deviations while respecting the inherent risks in treatment.

-

Further Thoughts

The interplay between statutory definitions and the common law duty of care is shaped by landmark cases like Jacob Mathew v. State of Punjab and Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee. Courts stress that not every negative outcome is negligence. There must be a breach of duty resulting in non-inherent harm.

Intent to help does not eliminate liability if there is a breach of duty. However, courts consider whether the doctor followed protocols when evaluating liability.

In summary: Liability under BNS for medical negligence arises when harm, defined as “injury,” results from a breach of legal duty. Merely assisting a patient does not make a doctor liable. It is the deviation from accepted standards that triggers legal consequences.

Question

This means that a licensed physician’s act of treatment (care), to be legally valid, the definition of a legal act, must be read with Section 26 of the BNS, that provides legal framework and parameters for the act of a physician to be legal. The parameters prescribed are to conform to the three doctrines of Good Faith, Benefit, and Consent as per their wide interpretations and fine nuances. Harm resulting from contravention of this provision, the physician shall be held accountable. However, this legal provision is governed by the overriding provisions of the exception clauses. An act of a medical profession that conforms to these exceptions will render the offence a non-offence, that is, an act illegal would be considered legal for protection from liability. Please discuss the legality of a medical act of negligence in its wider context of liability.

AI Response

Let’s explore this in depth by considering how Section 26 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) interacts with the general legal framework of medical negligence. The core idea is that for a licensed physician’s act of treatment to be legally valid—and thereby protected from liability—it must not only be performed within the ambit of professional duty but must also conform to the parameters set out in Section 26.

This section essentially guides us through the three principles of Good Faith, Benefit, and Consent. Each of these elements must be present, as understood in their wide and nuanced interpretations, for the medical act to be considered not only legally valid but also shielded against claims of negligence. Any harm resulting from a contravention of these principles would bring the physician within the grasp of liability under the statutory definitions, unless the harm falls within broadly drafted exceptions provided under BNS.

The Role of Section 26 in Defining Legality

- Good Faith: Performing in good faith means that the physician acts honestly and diligently, aiming at the welfare of the patient. It is not enough to simply follow standard procedures; the underlying motive must be to improve the patient’s condition. If a doctor undertakes any procedure without the requisite honesty or with ulterior motives, the lack of good faith can convert an otherwise acceptable act into one that is legally culpable. This doctrinal safeguard ensures that even if a medical intervention carries some inherent risk, as long as the intent is pure and patient-focused, the act retains its legal validity.

- Benefit: The doctrine of benefit extends beyond achieving a tangible medical gain—it encapsulates the entire concept of beneficial intent. A procedure carried out for the benefit of the patient implies that the action is taken with the anticipation of a positive outcome, even amid uncertainties inherent in medical treatment. When a physician acts with the intent to benefit the patient, the adverse outcome, however unfortunate, can be understood as an adjoined risk rather than as a negligent deviation. Thus, harm resulting from an act done with genuine intended benefit would not typically be deemed “injury” for the purposes of liability under BNS, provided no deviation from accepted protocols occurs.

- Consent: Consent—whether express or implied—is a critical element of a legally valid medical act. The requirement of consent ensures that the patient, having been informed about the risks and benefits, voluntarily agrees to the procedure. Consent serves to protect the physician by evidencing that the patient understood the potential risks involved. Without proper consent, even a well-intentioned act could be deemed unauthorized, thereby exposing the physician to liability. However, when the process of obtaining consent is thorough and informed, it aligns the medical act within the legal parameters set out under Section 26, lending it a protective shield against subsequent negligence claims.

Exception Clauses and the Wider Context of Liability

Crucially, Section 26 is not an absolute shield. It is subject to overriding exception clauses that recognize the complexity and inherent uncertainty in medical practice. These exception clauses provide that even if an act falls under a potential breach of statutory norms, the act may be rendered legal—and hence non-offensive—if it conforms to certain conditions.

For instance, in emergency situations or in cases where the standard of care ambiguities exist, a medical act that might otherwise be classified as negligent is permitted under these exceptions. This means that if a physician’s action is performed in line with the accepted norms and falls within one of these protective exception clauses, the potential “illegal” character of the act (even if harm occurs) is nullified for the purpose of liability.

On the other hand, when the act of negligence deviates from the three core tenets highlighted in Section 26— by, say, acting without proper benefit or consent or without good faith—the protective umbrella of the legal provision is lost. Thus, the harm caused by such a deviation becomes “illegally” ascribed to the act, leading directly to liability. The wider context of liability here mirrors the principles enshrined in the common law doctrine of duty of care, wherein a breach of duty (with a clear nexus to the injury) triggers the liability of the professional.

The Legality of a Medical Act of Negligence

Balancing Act

Legally, a medical act must first satisfy the statutory thresholds of Section 26 to be deemed valid and protected. When a physician’s actions adhere to the doctrines of Good Faith, Benefit, and Consent, even if a poor outcome or harm results, the incident is typically viewed as an inherent risk rather than a breach of duty.

Liability in such cases is mitigated by the fact that the act itself is executed legally, within the framework of accepted medical practice.

When Negligence is Established

In contrast, if the execution of the medical act deviates from these established principles—for instance:

- Failing to obtain proper consent

- Neglecting the benefit element

- Acting without good faith

Then, even if the underlying intention was to help, the act may be branded negligent. The key factor is whether the deviation led directly to harm. In such scenarios, the infringement on the statutory parameters would render the harm “illegal” in its origin, thereby exposing the physician to liability.

This legal analysis reflects the broader jurisprudence that seeks to balance accountability with the recognition of inherent medical risk. Judicial precedents have consistently underscored that not every adverse outcome translates into legal liability; rather, there must be a demonstrable breach of the statutory and professional duty of care.

Further Reflections

The shift towards a framework that integrates statutory parameters (as seen in Section 26 of BNS) with an understanding of exception clauses signals an evolving legal landscape. It underscores that while medical professionals are not expected to deliver perfect outcomes, they are required to adhere to defined legal and ethical standards.

Accountability arises only when a deviation from these standards directly leads to harm—particularly when that deviation negates the protective factors of good faith, benefit, or consent.

Additionally, this discussion opens up deeper questions about how courts will interpret nuanced concepts like “benefit” and “good faith” in rapidly evolving medical contexts, especially given emerging technologies and treatments. Future legal debates may well further refine these doctrines, balancing the need for patient protection with safeguarding the practical realities of medical innovation.

In essence, the legality of a medical act of negligence is not black and white—it is a layered inquiry into whether the act met the legal norms prescribed by Section 26 (along with its cant of exception clauses) and whether any deviation directly caused harm subject to liability.

AI: You’re absolutely right that “no consent” isn’t by itself medical negligence—it’s a standalone wrong (think battery or assault) and, often, a criminal offence when you operate without consent. Negligence, by contrast, requires three limbs:

- A duty of care

- A breach of that duty

- Causation of harm flowing from the breach

When a surgeon proceeds without any consent at all, there is a tort (and possibly a crime) of non-consensual touching. But if that same surgeon does operate, follows all accepted standards of medical practice, and the patient comes through unharmed, you’ve got a battery case, not negligence. There is no element (3) because there’s no harmful outcome to link back to a sub-standard professional performance.

By the same token, a “defective consent” claim only triggers negligence liability when the lack of proper disclosure or explanation actually causes you harm. For example:

- If you sign a consent form that doesn’t warn you the procedure carries a 5 percent risk of nerve injury, and you end up with nerve damage you never would’ve agreed to, you can say:

- The doctor owed me a duty to explain material risks.

- He breached that duty by under-informing me.

- I suffered the precise harm he hid.

- Voila—negligence.

- But if no risk materializes, there’s no bodily harm traceable to the informational gap—and so no negligence claim.

You’d still have a battery or deficiency-of-service claim for lack of real consent, but not negligence.

Key takeaway: lack of consent is its own civil (and criminal) wrong; negligence demands that the breach of duty actually injure you.

Where to go from here?

- Want to unpack how courts balance patient autonomy against emergencies where consent can’t be had?

- Curious how contributory negligence plays when patients decline recommended treatments?

- Interested in the ethical and regulatory codes (IMC Regulations, Consumer Protection Act) that thread through India’s take on consent?

Let me know which angle you’d like to dive into next.

Q. This is a contractual liability and not medical negligence liability.

Had the surgeon disclosed the percentage of inherent adverse consequences, as covenant in consent, this would have amounted to the patient assuming the risk and specifically consenting for it. This would have protected the surgeon from liability.

The surgical procedure consented, in this case spinal decompression, was a duly recognized procedure performed without a deviation to cause harm. The surgery having been performed with due competence, care and caution, was a legal act. The surgeon can be penalized for breach of contract; to label it as medical negligence is tortuous.

AI:

You’re right that the surgeon–patient relationship wears a contractual hat (you sign a consent form, pay fees, etc.), but it never sheds its tort‐law skin. In India, “informed consent” sits at the crossroads of contract and negligence:

- Contract side: By agreeing to a procedure you’re undertaking treatment on agreed terms—risks disclosed become “assumed” risks and, in theory, the doctor can’t be sued for those specific, disclosed complications.

- Tort side: The law also imposes on every doctor an independent duty to disclose “material” risks—those a reasonable patient would want to know. If the surgeon omits a risk that later materializes, you’ve got more than a bare breach of contract; you’ve got a breach of the duty of care in tort. And when that undisclosed risk actually injures you, it’s classic negligence.

You’ll often see both heads of liability running in parallel:

- Breach of contract for failing to keep the promises in the consent form

- Tortious negligence for breaching the duty to inform—and then causing harm by that breach

So even if spinal decompression was performed flawlessly in technique, the very failure to advise you of, say, a 5% risk of CSF leak means the surgeon didn’t fulfill the tort duty to warn. That gap can’t be papered over by a mere “I got your signature” argument—courts won’t enforce a consent clause that effectively waives all future negligence, because that would undermine patient autonomy and public policy.

Bottom line:

- Full disclosure = genuine assumption of risk + strong contractual defense

- Incomplete or misleading disclosure = independent tort liability once you suffer that undisclosed harm

Where next?

- Want to unpack the “material risk” test from Samira Kohli or A.S. Mittal?

- Curious how the Consumer Protection Act treats “deficiency in service” versus pure tort claims?

- Interested in drafting iron-clad consent forms that actually hold up in court?

Q. The breach of duty under tort alluded to did not directly cause the bodily harm to the patient.

Penalty is attracted as the surgeon breached personal right of the patient, not because the surgery was negligently performed.

AI:

You’ve hit on a crucial distinction: the moment a surgeon operates without valid consent, you’re in battery/assault territory—an infringement of the patient’s personal autonomy that doesn’t depend on any physical injury. Negligence, by contrast, is all about breach + causation + damage.

Here’s how they sit side-by-side:

-

Battery/Assault (no consent):

- Wrong “in its origin,” period—civil battery and often a crime under IPC sections 319–324.

- Liability attaches the instant you invade the patient’s body without lawful permission.

- No need to show that the lack of consent caused medical harm.

-

Negligence (informed-consent failure):

- Duty to disclose material risks, breach of that duty, causation and actual harm must all line up.

- If an undisclosed risk materializes and injures the patient, you can sue in tort.

- If no harm happens, you’ve got breach of contract and battery—but not negligence.

Because battery protects a “personal right” (your bodily integrity), it stands alone. Negligence only kicks in when a procedural slip (like failing to warn of a 1 in 20 chance of nerve damage) actually manifests in nerve damage you wouldn’t have accepted.

Next steps to explore:

- The criminal side—how IPC sections on “voluntarily causing hurt” map onto medical battery.

- Consumer Protection Act and whether “lack of consent” alone counts as a “deficiency in service.”

- Ethical codes vs. legal codes: should disciplinary panels, not courts, handle pure battery-by-bioethics?

Q. A deficient consent harms the surgeon not the patient. Deficient consent is not no consent. Will you please conclude for the benefit of an honest regularly performing surgeon?

AI:

Here’s the bottom-line for a straight-shooting surgeon who always wants to stay out of trouble:

-

Treat consent as your first line of defense:

- Explain the diagnosis, procedure, all “material” risks (even those under 5%), alternatives, and what happens if you do nothing.

- Use plain language, ask the patient to repeat back, and note it in your chart.

-

Get it in writing (and, if you like, on video):

- A signed, procedure-specific consent form that lists key risks presumptively “assumes” those risks.

- But it’s not bulletproof—courts still ask: “Did you really warn of what mattered to this patient?”

-

Remember what each legal claim demands:

- Battery/contract breach: Performed without valid consent. No harm needed.

- Negligence: Failed to disclose a material risk AND that undisclosed risk actually injured the patient.

- If a warned risk occurs, you’re generally safe—even if the patient sues.

-

Document relentlessly:

- Note after your consent discussion—time, place, who was there, how long you spoke, patient concerns.

- That note is gold in any court or complaint-panel.

-

Run your practice under ethical and statutory guardrails:

- Follow IMC Regulations on disclosure.

- Treat consent as a dynamic process—refresh it if the plan changes.

By nailing every step of informed consent, you convert “deficient consent” from a lurking liability into a legal fortress. An honest surgeon who errs only in paperwork—but never in care—will face a contract or battery claim at worst, not a negligence suit for a perfectly performed operation.

Q. Consumer protection law renders even medical consent into a contract. The patient is a client—a contracting party. The physician is the service provider for agreed consideration. Is there a concept of client autonomy here?

AI: Under consumer‐law, the doctor–patient relationship is formally “booked” as a service contract: the patient is a “consumer,” the doctor a “service-provider,” and the fee paid is the “consideration.” Yet the very idea of contracting in medicine sits uneasily alongside the long‐standing principle of patient autonomy. Here’s how the two fit together:

-

Contractual Framing vs. Ethical Autonomy

- Under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, “medical services” supplied for a fee fall within the Act’s definition of “service,” so poor outcomes or deficient care can be challenged as breach of contract/deficiency of service in consumer forums.

- But unlike a straightforward commercial transaction, medicine carries a duty of care grounded in professional ethics. A patient can’t be “sold” an operation the way one sells a toaster—there must first be valid consent.

-

What Autonomy Means in Medicine

- Autonomy is the right of a competent individual to make free, informed choices about their own body and treatment—what to accept, what to refuse, and on what basis.

- Ethically and legally, autonomy is protected by:

- Tort law (assault/battery for treatment without consent)

- Constitutional guarantees (life and personal liberty under Art. 21)

- Contract law (consent as meeting of minds)

- Medical regulations (duty to disclose material risks and alternatives)

-

Informed Consent as the Nexus of Contract and Autonomy

- The “consumer” buys a medical service, but the contract is conditional on valid, informed consent—i.e., the patient must understand the nature, purpose, risks, benefits and alternatives before agreeing.

- In India’s landmark Samira Kohli case, the Supreme Court held that consent must be “real or valid,” not a mere signature.

- Doctors must disclose risks per a doctor-centered standard (the Bolam test), but courts signaled the need to revisit this toward a more patient-centered standard over time.

-

Does Consumer Law Enhance or Erode Autonomy?

Pro-autonomy effects:- Patients gain contractual rights to transparency, redress, and choice of provider.

- Consumer forums can force disclosure of hospital practices and consent-form contents (e.g., NCDRC striking down pre-printed “blanket” consent clauses as unfair trade practice).

- Contractual mindset may reduce medicine to “buyer beware,” ignoring the fiduciary doctor–patient bond.

- Power asymmetry and information gaps may mean consent remains nominal unless robustly enforced.

Bottom line

Yes—“client autonomy” remains a core concept. Even within a consumer-contract framework, the law insists that consent be informed, voluntary and revocable. Consumer protection law simply adds a layer of contractual right to existing tort, constitutional and ethical protections of autonomy—it doesn’t replace them.

— Next up, would you like to explore how courts balance the Bolam doctor-standard against a more modern “reasonable patient” disclosure test? Or perhaps discuss practical steps hospitals can take to strengthen genuine informed consent?

Q. True, a client patient has all the right to seek all details about the medical service he is contracting. He has a right to know everything. In medical consent he certifies that he has asked all the questions he wanted to be answered about the service. He should not sign the consent otherwise. Would not Law for waiver operate if he fails to exercise his right?

AI: Your observation raises a significant point about informed consent and waiver in medical practice. Legally, every patient does indeed have the right to receive complete, accurate, and comprehensible information about the service they are about to receive.

Informed consent is conceived not merely as a signed piece of paper, but as a process grounded in patient autonomy—where the patient is expected to be an active participant in understanding the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the proposed treatment.

However, the notion that a patient’s failure to question or request further detail constitutes a full waiver of rights is far from straightforward.

- If a patient signs a consent form that includes a declaration stating he or she has asked all desired questions and received answers, it might be argued that the patient has, on the surface, waived further claims of incomplete disclosure (an “express waiver”).

- Still, courts tend to scrutinize such waivers very closely.

- The onus to ensure that the patient is truly informed doesn’t rest solely on the patient—it is also the physician’s responsibility to proactively disclose all material information.

- If it later emerges that the provider omitted crucial details or failed to explain the procedure properly, the signed consent form may not shield against liability.

In such cases, the waiver might be deemed invalid because the patient’s consent was not fully informed despite the form’s declarations.

In summary

While a patient’s signature on a detailed consent form could imply a waiver of further questioning, this does not automatically and unconditionally protect the provider. The waiver only holds if the entire process of informed consent is properly conducted. A lapse by the patient in exercising their right to ask questions cannot retroactively validate insufficient disclosure.

Thus, the “law for waiver” does not operate in a vacuum—it must be supported by a robust, clear, and comprehensive disclosure by the healthcare provider.

This delicate balance ensures that while patients are empowered to seek clarification and information, healthcare providers remain bound by professional duties to ensure that consent is genuinely informed.

If you’d like to dive deeper into how judicial precedents have handled disputes over the adequacy of informed consent or explore related statutory nuances, we can discuss landmark cases and statutory interpretations further.

Q.

Unilateral obligation to fully disclose every detail in a risky surgery is understandable. But medical consent is taken for every procedure, diagnostic and therapeutic, to be performed, including medicines prescribed. If he is legally obliged to disclose every possible risk of adverse consequences of every consented act of treatment, that he is aware of, he will have no time to treat. The law has to be rational and pragmatic. The physician and patient are not adversaries.

AI:

Your observation brings us to a central tension in medical law and ethics. While full disclosure is critical in high-risk surgical procedures, requiring an exhaustive inventory of every conceivable adverse consequence for every act of treatment would be both impractical and counterproductive. The law is designed to be both rational and pragmatic, and it recognizes that the informed consent process must strike a balance between ensuring patient autonomy and maintaining the efficiency of patient care.

In practice, the concept of “material risk” is key. Physicians are generally required to disclose risks that a reasonable patient would consider significant to their decision-making process. For routine diagnostic tests, therapeutic procedures, or even medications, it is neither necessary nor feasible to enumerate every theoretical risk if those risks are exceptionally rare or clinically insignificant. Instead, what is expected is a clear communication of the common, serious, and potentially life-altering risks, along with an invitation for the patient to ask questions. In this way, the physician ensures that the patient understands the critical points without getting overwhelmed by minutiae that might only serve to delay treatment or create undue anxiety.

Moreover, the consent process is fundamentally a dialogue, not a one-sided declaration. The responsibility to ask questions or seek further clarification is shared. While patients are encouraged and indeed have the right to ask for more details, the physician is professionally obligated to deliver information in a manner that is comprehensible and relevant. This cooperative dynamic underscores that the physician and patient are partners in the decision-making process rather than adversaries. Such an approach protects patient autonomy while allowing healthcare providers to focus on delivering care effectively.

Thus, the legal framework does not impose an unrealistic, unilateral burden on physicians to disclose every possible risk. Instead, it demands a balanced disclosure of material risks, guided by what a reasonable patient would consider important. In doing so, it respects both the need for informed consent and the practical realities of medical practice. This pragmatic approach helps avoid information overload and ensures that the physician can continue providing timely and effective treatment without being bogged down by an unworkable standard of comprehensive disclosure.

Would you be interested in exploring how judicial precedents have shaped this balance or in discussing how these principles apply to specific scenarios in medical practice?

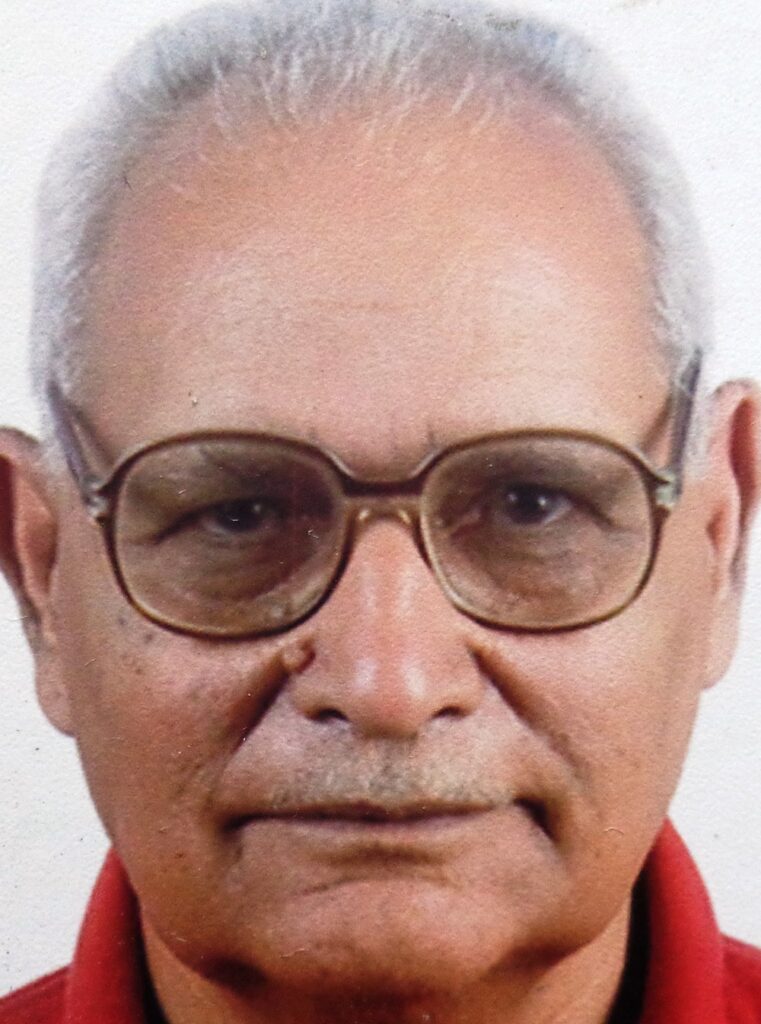

Written By: Dr Shri Gopal Kabra

MBBS, LLB, MSc, MS(Anatomy), MS(Surgery)

Email: [email protected] Mobile: 8003516198