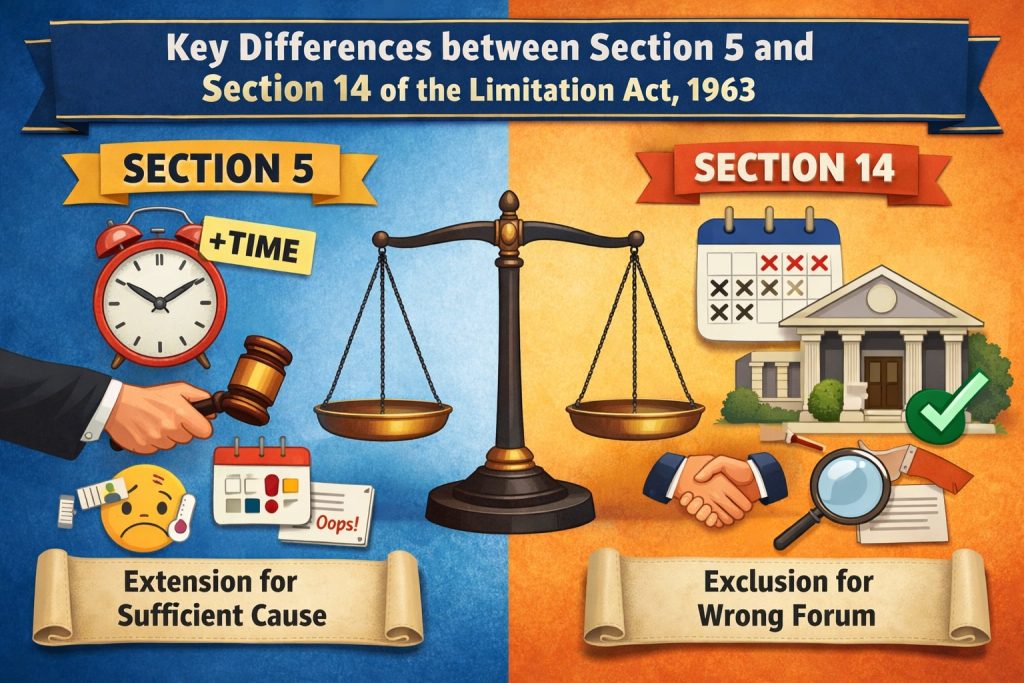

The key differences between Section 5 and Section 14 of the Limitation Act, 1963, stem from their distinct objectives, scope, and manner of application. Section 5 empowers courts to condone delay upon showing “sufficient cause,” thereby operating as a discretionary relief primarily applicable to appeals and certain applications.

In contrast, Section 14 provides for the exclusion of time spent in bona fide prosecution of proceedings before a court lacking jurisdiction, functioning as a substantive right rather than a matter of discretion. While Section 5 focuses on justifying delay, Section 14 addresses the equitable exclusion of time lost due to procedural defects, reflecting their differing legal purposes and practical operation.

|

Aspect |

Section 5 – Limitation Act, 1963 |

Section 14 – Limitation Act, 1963 |

|

1. Purpose |

Helps a person who files an appeal or application late by allowing the court to forgive the delay. |

Helps a person by ignoring the time lost in a case filed honestly in the wrong court. |

|

2. Nature |

The court has full freedom to accept or reject the reason for delay. |

The court must give benefit once legal conditions are fulfilled. |

|

3. Proceedings covered |

Applies only to appeals and certain applications. This means the court can forgive delay if an appeal or application is filed late, but it cannot be used for filing a suit late. |

Applies to suits and applications. If a person honestly files a case or application in the wrong court, the time spent there can be ignored when filing the case again in the correct court. |

|

4. Application to suits |

Cannot be used to file a suit after limitation. |

Can be used when filing a fresh suit after earlier failure. |

|

5. Reason required |

Person must clearly explain why the delay happened and justify it. |

No need to explain delay; only honesty and careful action matter. |

|

6. Good faith |

Honesty is not compulsory but helps the case. |

Honesty is compulsory and strictly checked. |

|

7. Due diligence |

Law does not strictly require careful and continuous effort. |

Person must act carefully and without unnecessary delay. |

|

8. Cause allowed |

Many reasons like illness, mistake, poverty, or accident are accepted. |

Only reasons like lack of jurisdiction or similar legal defect are accepted. |

|

9. Type of relief |

Extra time is added beyond the limitation period. |

Time wasted earlier is subtracted from limitation calculation. |

|

10. Court’s power |

Court decides based on facts and fairness. |

Court has little discretion once conditions are satisfied. |

|

11. Criminal cases |

Can apply to some criminal appeals if law allows. |

Does not apply to criminal matters. |

|

12. Negligence |

Minor carelessness may still be forgiven. |

No benefit if there was carelessness or inactivity. |

|

13. Same party / relief |

No requirement of same parties or same relief. |

For Section 14, this is explicitly required under sub-section (2) for applications (“against the same party for the same relief”). For suits (sub-section (1)), it’s framed as the proceeding being “against the defendant” and relating to the “same matter in issue” (not identical phrasing, but implies similar alignment). |

|

14. Same issue |

No requirement that issues must be the same. |

Earlier and later cases must involve the same issue. This directly applies to suits under Section 14(1) (“same matter in issue”). For applications under Section 14(2), it’s “same relief” rather than “issue.” |

|

15. Misjoinder |

Misjoinder is not treated as a valid ground. |

Misjoinder is clearly treated as a valid legal reason. |

|

16. Tribunals |

Section 5 is often expressly excluded in special statutes (e.g., under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, or Consumer Protection Act, 2019), |

Section 14’s principles (not the section itself) are applied analogously by courts/tribunals for equity, even if not statutorily incorporated (e.g., in M.P. Steel Corpn. v. CCE, (2015) 7 SCC 58). |

|

17. Effect on limitation |

Limitation period is extended. |

Limitation period is recalculated after removing wasted time. |

|

18. Standard used |

The court follows a broad and flexible approach. It mainly looks at fairness and justice and checks whether the reason for delay is reasonable. Different situations like illness, mistake, or hardship can be accepted, depending on the facts of the case. |

The test is stricter and more objective. The court carefully checks whether the earlier case was filed honestly (good faith), pursued with proper care (due diligence), and failed only because of a legal mistake, such as lack of jurisdiction. If any of these conditions are missing, the benefit is not given. |

|

19. Special laws |

Many special laws (such as laws creating special tribunals or authorities) clearly say that delay cannot be condoned. In such cases, even if there is a good reason, the court or tribunal cannot use Section 5 to extend the limitation period. |

In contrast, the principle of Section 14 is often applied even when Section 5 is barred. Courts try to ensure fairness by excluding the time spent in a case that was honestly filed in the wrong forum, so that a person is not punished for a genuine legal mistake under a special law. |

|

20. Court approach |

Courts are indeed liberal for both, but for Section 5, the explanation must often cover the entire period of delay (including day-to-day in prolonged delays, per Balwant Singh v. Jagdish Singh, (2010) 8 SCC 685). |

For Section 14, no such granular explanation is needed if conditions are met. |

|

21. Comparative Breadth |

Section 5 is broader as compared to Section 14. |

Section 14 is narrower as compared to Section 5. |

|

22. Scope of Application |

Not limited to courts of original jurisdiction but also to appellate court. |

Limited to courts of original jurisdiction. |

|

23. Extension v. Exclusion of Time |

Extension of prescribed period. It deals with extension. |

Exclusion of time of proceeding. It deals with exclusions. |

|

24. Discretionary v. Mandatory |

Extension of period is discretionary. |

Exclusion of time is mandatory. |

|

25. Flexibility of Good Faith and Due Diligence |

Good faith and due diligence are not applicable more rigidly. |

Good faith and due diligence are applicable more rigidly. |

In the landmark case of Ramlal, Motilal and Chhotelal v. Rewa Coalfields Ltd. (AIR 1962 SC 361), the Supreme Court of India highlighted a crucial distinction between Section 5 and Section 14 of the Limitation Act (then the 1908 Act, now the 1963 Act) while interpreting the scope of condonation of delay under Section 5.

The Court emphasized that, unlike Section 14 (where bona fides and due diligence play a central role in excluding time spent in a wrong forum), Section 5 does not confer an automatic right to condonation even when sufficient cause is established. The Supreme Court observed:

“It is, however, necessary to emphasize that even after sufficient cause has been shown, a party is not entitled to the condonation of delay in question as a matter of right. The proof of a sufficient cause is a condition precedent for the exercise of the discretionary jurisdiction vested in the court by Section 5. If sufficient cause is not proved nothing further has to be done; the application for condoning delay has to be dismissed on that ground alone.”

This passage underscores the discretionary nature of relief under Section 5: proving “sufficient cause” is mandatory (a precondition), but even upon proof, the court retains wide discretion to grant or refuse condonation based on facts, justice, and equity. In contrast, Section 14 operates more mandatorily—if the strict conditions (good faith, due diligence, jurisdictional defect or like cause) are met, exclusion of time is a substantive right, not discretionary.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Section 5 and Section 14 of the Limitation Act, 1963 address delay in different ways. Section 5 helps when a person files an appeal late due to reasons like illness or a genuine mistake—for example, if an appeal is filed ten days late because the lawyer was hospitalised, the court may condone the delay after hearing the explanation. Section 14, however, helps when time is wasted due to an honest legal mistake, such as filing a suit in a court that has no jurisdiction; in such a case, the time spent in the wrong court is excluded when the suit is filed again in the correct court. Thus, while Section 5 forgives delay based on sufficient cause, Section 14 ensures that a bona fide litigant is not punished for choosing the wrong forum, and both provisions aim to advance justice rather than defeat it on technical grounds.