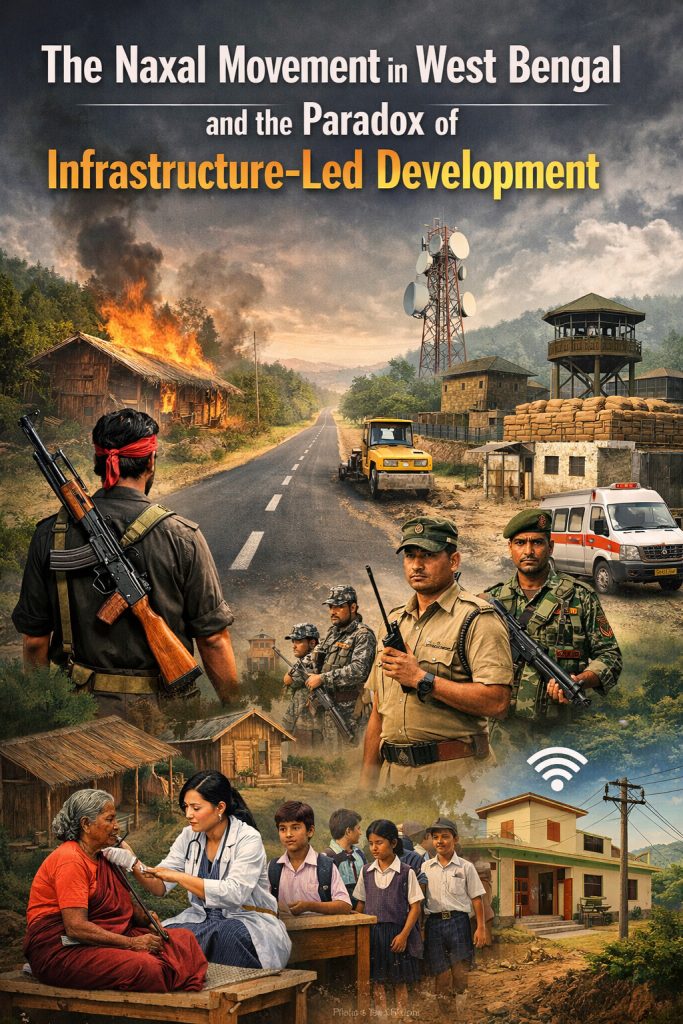

The Naxal movement in West Bengal, originating in the 1967 Naxalbari uprising and witnessing a major resurgence during the late 2000s—particularly through the Lalgarh agitation and Maoist activities in the Junglemahal region—posed a significant internal security challenge to the state. Districts such as Paschim Medinipur (including present-day Jhargram), Bankura, Purulia, and parts of Birbhum were severely affected. Rooted in land alienation, tribal marginalisation, exploitation of natural resources, unemployment, poor infrastructural facilities, illiteracy, extreme poverty, and enduring governance deficits, the insurgency compelled both the state and central governments to adopt an integrated security–development strategy.

Paradoxically, the persistence of the movement accelerated infrastructure development in these historically neglected, forested, and remote tribal regions. What began as security-driven intervention gradually evolved into broader civilian benefits, transforming isolation into connectivity and opportunity.

Strengthening Rural Connectivity through All-Weather Roads

One of the most tangible outcomes of the counter-insurgency response was the rapid construction of all-weather pacca roads in previously inaccessible areas. Under schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY), districts classified as Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) affected received priority funding and relaxed norms, including connectivity for habitations with smaller populations in critical blocks.

These roads served dual objectives. From a security perspective, they replaced vulnerable kuccha tracks that were susceptible to landmine and IED attacks, enabling safer and faster movement of security forces and logistics. Simultaneously, they connected remote villages to markets, schools, healthcare facilities, and administrative centres, reducing isolation and stimulating economic activity. Post-2011, as state responses intensified, PMGSY implementation in Junglemahal was fast-tracked, with West Bengal benefiting substantially from the national push to enhance connectivity in LWE regions.

Security Infrastructure and Permanent State Presence

Sustained counter-insurgency operations required the establishment of permanent security infrastructure. Significant investments were therefore made in fortified police stations, barracks, and camps for state police and Central Armed Police Forces. Police outposts were established in interior areas, gradually dismantling insurgent control over so-called “liberated zones.” Administrative buildings, often co-located with security facilities, also functioned as points of welfare delivery.

This enhanced and continuous state presence altered local power dynamics, reduced insurgent influence, and enabled sustained community engagement and governance in regions previously beyond effective administrative reach.

Expansion of Electricity, Internet, and Mobile Connectivity

Modern security operations depend heavily on reliable power supply and digital coordination. Consequently, electricity infrastructure was expanded to support camps, offices, surveillance systems, and civilian needs. Parallel investments were made in mobile towers and internet connectivity, even in dense forest and tribal belts, including central projects that specifically targeted LWE-affected areas in West Bengal and later upgraded networks to 4G.

These initiatives produced substantial civilian spillovers. Digital governance and real-time monitoring of development projects became possible; villagers gained access to online education, banking, telemedicine, and communication services; and remote regions were integrated into the broader state and national digital ecosystem.

Improvement in Medical Infrastructure and Emergency Response

The deployment of security forces necessitated improved medical preparedness, leading to the upgradation of Primary Health Centres and rural hospitals, strengthening of medicine supply chains, and deployment of ambulances and emergency evacuation facilities. The increased presence of trained medical personnel in underserved areas gradually benefited the wider rural and tribal population, contributing to improved healthcare access in the Junglemahal region.

Enhanced Monitoring and Execution of Development Projects

In Naxal-affected blocks, development works came under heightened administrative and security oversight. Roads, irrigation projects, housing schemes, MGNREGA, and other welfare initiatives were closely monitored, reducing opportunities for corruption and fund diversion. Strict timelines and continuous supervision resulted in faster project completion and improved delivery to intended beneficiaries. Security-linked governance thus helped translate public expenditure into tangible outcomes.

Socio-Economic Spillover Effects

The cumulative impact of these interventions produced measurable socio-economic gains. Improved mobility enhanced agricultural marketing, livelihoods, and non-farm employment opportunities. Better infrastructure contributed to higher school attendance, increased healthcare utilisation, and greater participation of women in economic and social activities. Reduced fear and insecurity enabled deeper community engagement with local governance and democratic processes.

Over time, development itself emerged as a powerful counter-insurgency tool, addressing some of the structural grievances that had sustained the movement and contributing to the sharp decline of Naxal influence in West Bengal since the early 2010s.

Employment as a De-radicalisation Strategy

A crucial complementary measure involved targeted employment generation. Large numbers of local youth were recruited as home guards, junior constables, and in other government services by the state government. This approach provided stable livelihoods in regions marked by chronic unemployment, reduced the appeal of insurgent ideology by offering dignity and economic security, and leveraged local knowledge to strengthen policing and intelligence. By transforming potential recruits into stakeholders of the state, employment functioned as an effective tool of de-radicalisation, social integration, and trust-building.

Critical Perspective: Development Driven by Security

Despite substantial gains, the development trajectory had limitations. Initial interventions were largely security-centric, prioritising operational needs over purely people-centric priorities. Certain local aspirations—such as deeper land reforms or greater tribal autonomy over resources—were subordinated to immediate counter-insurgency objectives. Infrastructure alone proved insufficient to build lasting trust; sustained political dialogue, social justice measures, and participatory governance remained essential.

Conclusion

The Naxal movement in West Bengal illustrates a striking paradox: an insurgency fuelled by underdevelopment ultimately triggered accelerated, security-linked infrastructure transformation in the remote Junglemahal region. All-weather roads, electricity, mobile and internet connectivity, upgraded healthcare facilities, strengthened state presence, and rigorous monitoring of development projects have collectively bridged longstanding developmental gaps.

As Naxal activity in West Bengal has been largely suppressed—with only sporadic remnants remaining and the national footprint shrinking significantly by the mid-2020s—the experience offers an important policy lesson. Integrated security-development strategies can convert conflict zones into corridors of growth and inclusion. The enduring challenge lies in sustaining these gains in a post-conflict environment, ensuring that development remains inclusive, participatory, and responsive to local aspirations so that the grievances that once fuelled insurgency do not resurface.