Introduction

Helicopter travel is now a vital part of VVIP movement around the world. In countries with large distances, difficult terrain, insurgency-affected areas, poor road networks, or heavy city traffic, helicopters offer speed, flexibility, and access that no other transport can match. For VVIPs such as heads of government, senior ministers, military leaders, and foreign dignitaries, helicopters are often the most practical—and sometimes the only—way to travel.

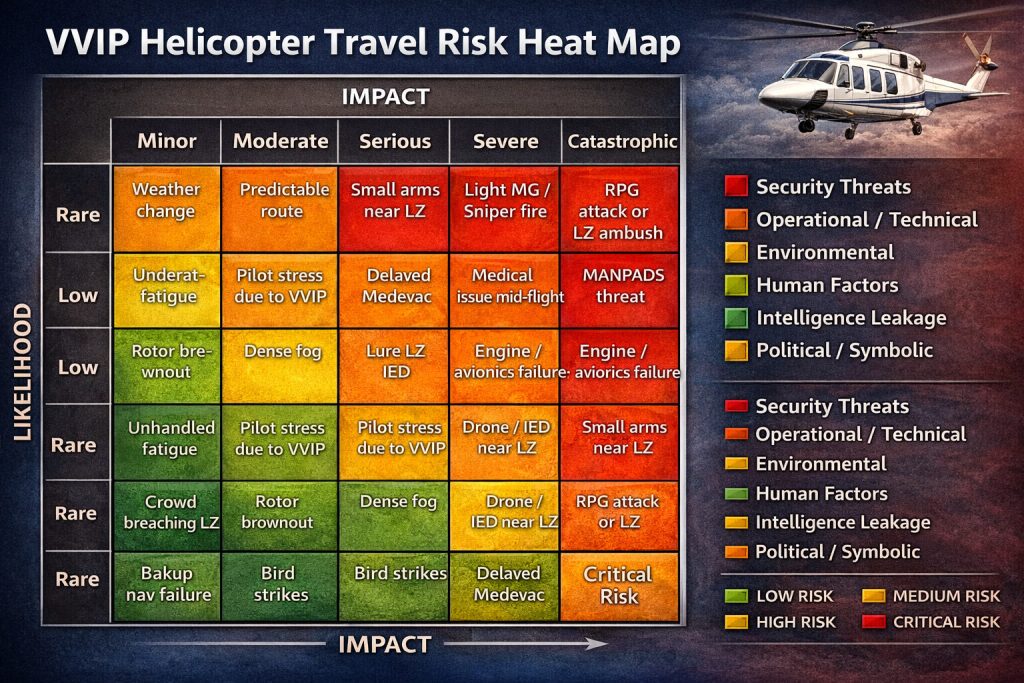

While helicopters reduce risks linked to road travel, such as ambushes, traffic jams, and landmine attacks, they create a different set of challenges. These include aviation risks, security threats, weather conditions, mechanical limits, human error, and wider strategic consequences. Unlike airplanes, helicopters fly low, use limited and often predictable routes, and depend heavily on weather, terrain, and technical reliability. Because of this, VVIP helicopter travel is a balance between operational need and higher risk.

Strategic Importance and Inherent Vulnerability of Helicopter Travel

Helicopters are valuable because they can land in small spaces, avoid dangerous or crowded roads, reach remote areas, and save a lot of time. These advantages are especially important during elections, disaster relief, counterinsurgency operations, and busy political schedules.

However, the same strengths also create risks. Flying at low altitude makes helicopters vulnerable to gunfire from the ground, difficult terrain, and easy visual tracking. Compared to airplanes, helicopters are slower, have fewer defensive manoeuvres, and are less able to survive modern attacks. Helicopter operations also depend on perfect coordination between pilots, ground security forces, intelligence agencies, and air traffic control. For a VVIP, a helicopter is not just a means of transport—it is a high-value, highly visible, and symbolically important target.

Security and Threat-Based Risks

One of the greatest risks to VVIP helicopter travel comes from ground-based attacks. Flying at low altitude makes helicopters vulnerable to gunfire, sniper shots, light machine guns, and, in high-risk areas, rocket-propelled grenades. Take-off, landing, and hovering are especially dangerous, as helicopters have minimal time or space to react. Even a single hit to critical components—such as the tail rotor, fuel line, hydraulic system, or avionics bay—can cause catastrophic failure.

A more severe threat is posed by portable missile systems (MANPADS). Though rare, these heat-seeking missiles are often deadly due to short attack distances and the limited time available to deploy countermeasures. Intelligence indicating the presence of MANPADS may render helicopter travel too risky.

Drone threats are an emerging concern. Drones can observe, track, or even carry explosives to attack helicopters, particularly near helipads and landing zones, where helicopters are slow and low. Drone swarms are especially dangerous and difficult for traditional security systems to counter.

Fortunately, advances in countermeasures—including electronic warfare systems, interception nets, and advanced DIRCM technologies—enhance protection against both missile and drone threats.

Finally, predictability remains a major vulnerability. Helicopters often follow fixed routes and schedules due to terrain, airspace rules, and fuel limitations, making it easier for attackers to plan ambushes or exploit leaked information.

Operational and Technical Risks

Helicopters are complex machines that face constant vibration, heavy stress on parts, and very little margin for error. If there is an engine failure, tail rotor problem, transmission fault, or hydraulic failure, the situation can become critical very quickly. Unlike airplanes, helicopters cannot glide safely for long, so pilots have very limited options during a major failure.

Even though modern helicopters have safety backups, there are real limits. A single-engine helicopter has no alternative if the engine stops. Autorotation can save lives, but it demands very high pilot skill, instant decisions, and suitable ground to land on—conditions that are often not available in cities or forest areas. For a VVIP, even a crash-free emergency landing can create a serious security problem on the ground.

Landing zones are among the most dangerous parts of helicopter operations. VVIP flights often use temporary or improvised landing sites that may not be fully checked or secured. Dangers include unseen wires, trees, poles, crowd intrusion, hidden explosives, and dust or debris that reduces visibility during landing. This is the point where flight risks and ground security risks come together, making it especially dangerous.

Environmental and Weather-Related Risks

Helicopters are exceptionally sensitive to weather conditions. Fog, low visibility, heavy rain, strong winds, turbulence, dust storms, or snowfall can rapidly degrade flight safety. Sudden weather deterioration may force emergency landings, disrupt navigation, or cause spatial disorientation. Globally, weather-related factors account for a significant proportion of helicopter accidents.

Terrain further compounds these hazards. Operations over mountains, dense forests, river valleys, and urban high-rise clusters introduce risks such as wind shear, updrafts and downdrafts, reduced radar coverage, and a lack of suitable emergency landing sites. High-altitude environments additionally reduce aircraft performance due to lower air density, affecting lift and engine efficiency.

Bird strikes and wildlife hazards are another underappreciated risk. Low-altitude flight near wetlands, forests, or agricultural zones increases the likelihood of bird strikes, which can damage windscreens, rotors, or engines and force sudden evasive manoeuvres.

Real-world VVIP helicopter incidents, such as the 2021 Mi-17 crash that claimed India’s CDS Bipin Rawat or the 2009 crash involving YSR Reddy, illustrate that such accidents typically arise from a combination of factors — adverse weather, human error, and maintenance or operational pressures. These cases underscore how conceptual risk frameworks align with reality, highlighting the critical need to account for both environmental and human factors in VVIP air transport safety.

Human Factors and Crew-Related Risks

Human factors remain one of the most critical and unpredictable risk variables. VVIP helicopter missions impose immense cognitive load on pilots and crew, combining tight schedules, threat awareness, complex coordination, and intense psychological pressure. Fatigue, stress, and prolonged duty hours can erode situational awareness, slow reaction times, and impair judgment.

Communication failures—whether between pilots and air traffic control, aircrew and ground security, or multiple helicopters operating in formation—can result in near-misses, incorrect landings, or airspace violations. In high-threat environments, clarity and discipline in communication are vital.

The presence of a VVIP can also introduce “authority gradient risk,” where pilots may feel implicit pressure to continue missions despite unsafe conditions or hesitate to report technical concerns. History has shown that such dynamics have contributed to otherwise avoidable aviation accidents.

Intelligence, Information, and Cyber Risks

VVIP helicopter operations are highly sensitive to intelligence compromise. Leaks regarding flight timing, routes, or landing zones—whether through human sources, unsecured communications, or social media—can allow adversaries to prepare attacks. In the digital age, real-time tracking and inadvertent disclosures pose serious operational risks.

Electronic interference adds another layer of vulnerability. Helicopters rely heavily on GPS, radio communication, and electronic navigation systems. GPS spoofing, jamming, or radio interference can degrade situational awareness, mislead navigation, or disrupt coordination, particularly in hostile or technologically contested environments.

Medical, Emergency, and Post-Incident Risks

Helicopters offer limited space and medical capability. A sudden in-flight medical emergency involving a VVIP may necessitate an unscheduled landing in an insecure or unsuitable area. In the event of a forced landing or crash, securing the VVIP becomes an immediate priority, often under conditions of confusion, injury, and emerging secondary threats. Delays in medical evacuation or reinforcement can rapidly escalate the situation.

Symbolic, Political, and Psychological Risks

Any incident involving a VVIP helicopter carries disproportionate symbolic and political consequences. Even non-fatal incidents attract intense media scrutiny, trigger political controversy, and may undermine public confidence in state institutions. For adversaries, such incidents offer immense propaganda value, allowing them to project strength or embarrass the state without necessarily inflicting physical harm.

Risk Mitigation: Balancing Necessity and Safety

Despite the risks, helicopters are still essential for VVIP travel. The goal is not to remove all risk, but to manage it carefully and professionally. This requires intelligence-based threat assessments, reliable twin-engine and well-maintained helicopters, highly trained pilots, proper crew rest, and secure, controlled landing areas. Routes and schedules should be kept unpredictable, with strong coordination between air and ground teams and strict rules on weather-related no-go decisions. Most importantly, the system must support pilots in aborting missions without fear or pressure, because safety must always come first.

Helicopter safety has generally improved, with professional operations showing lower fatality rates. VVIP flights are even safer, thanks to highly trained crews and rigorous maintenance, yet they remain riskier than fixed-wing flights due to low-altitude operations. Elite protocols mitigate risk, but inherent helicopter vulnerabilities persist in VVIP transport.

Helicopters Should Always Be Twin-Engine

A twin-engine helicopter provides a critical safety margin. If one engine fails, the other can keep the aircraft airborne long enough to land safely. This is especially important during take-off, landing, or flight over cities, forests, water bodies, or hostile areas—where emergency options are limited.

Single-engine helicopters offer no engine backup and depend entirely on autorotation, which is risky and depends on suitable terrain. For VVIP movement, this level of risk is unacceptable. Therefore, as a standard security and aviation safety requirement, only twin-engine helicopters should be used for VVIP travel, without exception.

In reality, some governments or militaries sometimes operate single-engine helicopters in lower-risk situations, often for reasons of cost or logistical convenience.

Helicopter Return Due to Weather: A Critical Security Consideration

Helicopters may sometimes turn back after take-off without reaching their destination because of fog, poor visibility, or sudden bad weather. In such situations, the aircraft can return to the helipad much earlier than expected. Therefore, security personnel deployed for VVIP duty at the helipad must always keep this possibility in mind. They should not disperse or relax security arrangements on the assumption that the VVIP will return only after a fixed time. Full security cover must remain in place until the helicopter has safely reached its destination and official clearance is given.

Presence of Armed Security Personnel in VVIP Helicopters

Armed security personnel should remain onboard the VVIP helicopter at all times. Their presence is essential to provide immediate protection during flight, landing, take-off, and in the event of an emergency or forced landing. If the helicopter has to land unexpectedly due to weather, technical issues, or security threats, onboard armed personnel can instantly secure the area, protect the VVIP, and respond to any hostile situation until ground support arrives. This onboard security layer is a critical component of comprehensive VVIP protection and must never be treated as optional.

Further, their presence allows an immediate armed response. If miscreants open fire on the VVIP helicopter during low-level flight, take-off, or landing, onboard security personnel can return fire to suppress the threat, create a protective window for escape or emergency landing, and deter continued attack. This capability significantly enhances survivability during the most vulnerable phases of helicopter operations.

Conclusion

Helicopter travel for VVIPs has clear advantages—it is fast, flexible, and useful in critical situations. At the same time, it carries serious risks because it is highly visible and vulnerable. These risks include security threats, technical failures, weather conditions, human error, intelligence leaks, and even political fallout.

The real danger is not the helicopter itself, but complacency and overconfidence. Safety depends on strict discipline, realistic planning, and a strong safety culture. Calling off a flight when conditions are unsafe is not a failure—it is a sign of professional judgment. In VVIP security, a helicopter is a strategic asset in motion, and its risks must be clearly understood, respected, and carefully managed at all times.