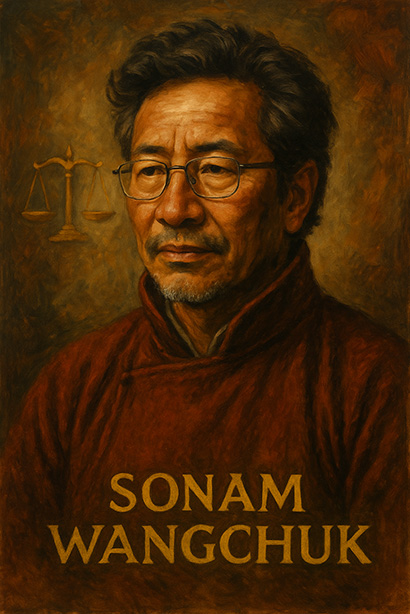

The detention of Ladakh-based climate activist Sonam Wangchuk under the National Security Act, 1980 (NSA) has ignited intense legal and public debate across India. The case has brought into sharp focus the delicate balance between state security imperatives and constitutional guarantees of personal liberty, especially in a democratic setup committed to the rule of law.

While the authorities informed the Supreme Court of India that Wangchuk himself has not made a formal representation challenging his detention, his wife, brother, and legal counsel have been active participants in the judicial proceedings, raising serious constitutional, procedural, and human rights concerns.

Background of the Case

Sonam Wangchuk, globally recognized for his environmental innovations and educational initiatives in Ladakh, was detained on September 26, 2025, under Section 3(2) of the National Security Act, 1980, by the District Magistrate of Leh.

This provision empowers the executive authority to order preventive detention if it is satisfied that such action is necessary to prevent a person from acting in a manner prejudicial to the defense of India, the security of the State, public order, or the maintenance of essential supplies and services.

Wangchuk’s wife, Dr. Gitanjali J. Angmo, subsequently filed a habeas corpus petition before the Supreme Court, alleging that the detention order was illegal and arbitrary, as the grounds of detention were not initially furnished, violating Article 22(5) of the Indian Constitution.

This Article mandates that a person detained under preventive detention laws must be informed of the reasons for detention and be given an opportunity to make a representation against the order “as soon as may be.” This lapse, if established, strikes at the very core of the constitutional safeguards designed to prevent misuse of preventive detention powers.

Legal Developments in the Supreme Court

On October 6, 2025, the Supreme Court issued notices to the Union Government and the Union Territory of Ladakh, directing them to respond to the habeas corpus plea.

The Leh administration, in its affidavit, defended the detention as lawful and necessary, stating that the District Magistrate “was satisfied and continues to be satisfied” regarding the necessity of the detention, invoking the subjective satisfaction clause under the NSA.

During the subsequent hearing on October 15, the Solicitor General, Tushar Mehta, informed the Court that the grounds of detention had now been provided to Wangchuk’s wife, thereby enabling her to amend her petition to challenge the substantive validity of those grounds.

The Court permitted such an amendment and adjourned the matter to October 29, 2025, for further hearing.

Procedural and Constitutional Issues

1. Representation and Access to Counsel

While the authorities have claimed that Wangchuk himself has not filed any representation, this raises questions regarding his effective access to legal assistance.

- Under Article 22(1), every detainee has a right to consult and be defended by a legal practitioner of their choice.

- If practical obstacles prevent the detainee from exercising this right, the legitimacy of the detention becomes questionable.

The Court allowing Wangchuk to exchange written notes with his wife suggests a limited but significant acknowledgment of communication rights under humanitarian and constitutional principles.

2. Delay in Furnishing Grounds of Detention

The initial failure to provide the grounds of detention constitutes a grave procedural irregularity.

| Provision | Requirement | Legal Consequence of Violation |

|---|---|---|

| Section 8(1) NSA | Grounds must be communicated within 5 days (extendable to 10 in exceptional cases) | Detention vulnerable to invalidation |

| Article 22(5) Constitution | Detainee must be informed and given an opportunity to represent | Violation strikes at constitutional safeguard |

In Icchu Devi Choraria v. Union of India (1980) 4 SCC 531, the Supreme Court held that failure to promptly communicate the grounds of detention and denial of effective opportunity to make a representation violates Article 22(5) and vitiates the entire detention.

3. Subjective Satisfaction and Judicial Review

Preventive detention under the NSA operates primarily on the “subjective satisfaction” of the detaining authority. However, courts retain the power of judicial review to assess whether such satisfaction was based on relevant material or was mala fide or arbitrary.

In A.K. Roy v. Union of India (1982) 1 SCC 271, the Supreme Court held that although preventive detention laws are constitutionally valid, they must be exercised strictly within the confines of procedural safeguards.

Therefore, in Wangchuk’s case, the Supreme Court is expected to scrutinize whether the detention was proportionate, necessary, and founded on cogent material—especially since his activism pertains to environmental and social causes, not violent or subversive acts.

4. Article 21 and the Doctrine of Proportionality

In recent years, the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty) has evolved to include the principle of proportionality as a standard for testing preventive detention orders.

In Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2020) 3 SCC 637, the Court emphasized that restrictions on fundamental rights must be necessary, proportionate, and least intrusive.

Applying this test, Wangchuk’s detention raises serious concerns about whether preventive detention—a tool meant for grave threats to national security—was a proportionate response to peaceful environmental activism.

Broader Constitutional and Democratic Implications

The detention of Sonam Wangchuk illustrates the perennial conflict between civil liberties and national security in India’s constitutional framework.

- Preventive detention laws like the NSA were designed as exceptional mechanisms.

- Their recurrent use against dissenters, journalists, and activists has been widely criticized as contrary to democratic principles.

- This case tests the limits of state power and the robustness of judicial oversight.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of strict scrutiny, it could reaffirm the doctrine that personal liberty is the rule and preventive detention the exception.

Potential Precedents and Impacts

- Clarifying the timeliness and sufficiency of detention grounds under Article 22(5).

- Defining the standard of judicial review for subjective satisfaction under preventive detention laws.

- Reinforcing protection of civil liberties in cases involving peaceful activism.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s handling of the Sonam Wangchuk case represents a crucial test for India’s constitutional democracy. It will determine whether preventive detention can be used as a blunt instrument against dissenting voices or must remain a measure of last resort, tightly circumscribed by procedural fairness and judicial oversight.

At its core, this case reaffirms the timeless constitutional principle that “liberty is not a gift of the State, but a fundamental right guaranteed against it.”

The outcome will not only shape Wangchuk’s fate but also define the contours of civil liberties, judicial accountability, and executive restraint in contemporary India.