Free and fair elections are the foundation of a democracy. In India, the system is designed to make sure elections happen on time and without interruptions. A key part of this system is a simple but powerful rule: you cannot legally challenge an election while it is happening. You have to wait until the entire process is finished.

This important rule was established by the Supreme Court in a famous case, N.P. Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer, Namakkal Constituency (AIR 1952 SC 64)., and it is still followed today.

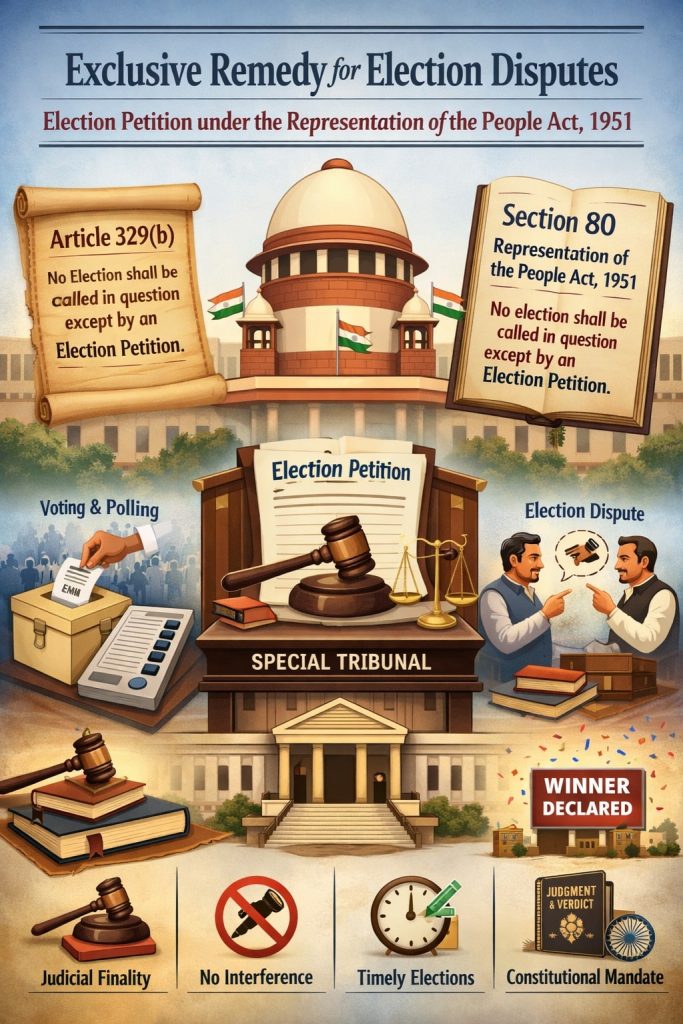

The Law’s Clear Rule

The law, specifically the Representation of the People Act, 1951, has a section (Section 80) that states this very clearly. It says that the only way to question the result of an election is by filing a special complaint called an “election petition” after the election is complete.

Any problem—like a candidate’s nomination being wrongly rejected, claims of cheating, or other mistakes—must wait. This petition is then heard by a High Court, which acts as a special court for these disputes.

The Constitution’s Support

This rule is also supported by the Constitution of India – Article 329(b). The Constitution’s writers wanted to prevent courts from interfering during an election. They believed this was necessary to avoid delays and protect the election process from being disrupted.

The Famous Case that Set the Precedent

In the 1952 Ponnuswami case, a man’s application to be a candidate was rejected. He immediately went to court to challenge this decision before the election had even taken place.

The Supreme Court said no. The Court explained three main points:

- An “election” is the entire process, from the announcement of the election to the final declaration of the winner.

- You cannot file a legal complaint about any part of this process until it is completely finished.

- The only legal tool you can use is an election petition, and you can only use it after the voting is over.

The judges warned that if people could go to court over every issue during an election, it would cause chaos, create endless delays, and ultimately harm democracy.

Why This Rule is So Important

The Supreme Court gave several simple reasons for this rule:

- To Finish on Time: Allowing lawsuits in the middle of an election would paralyze the system and prevent it from being completed on schedule.

- To Get a Clear Result: Elections need to end with a definite winner, not with the result tied up in courts for months or years.

- To Use the Right Experts: High Courts are specially designated to handle these specific election-related disputes, ensuring they are dealt with properly.

- To Protect the Public: The smooth functioning of the entire democratic system is more important than any single person’s grievance during the election.

Exceptions and Limits

Under Article 329(b) of the Indian Constitution, the general principle is that no election to Parliament or a State Legislature can be challenged during the electoral process; disputes must await the filing of an election petition only after the entire process—from notification to result declaration—is complete, as affirmed in N.P. Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer (1952), which defined “election” as a comprehensive procedural continuum shielding it from interim judicial intervention.

However, this prohibition is not absolute and allows narrow exceptions: the constitutional validity of electoral laws may be contested (Hari Vishnu Kamath v. Syed Ahmad Ishaque, 1955), disqualification issues under Articles 191 and 193 that are independent of the electoral process are reviewable (K. Venkatachalam v. A. Swamickan, 1999), and actions that obstruct or undermine free and fair elections—not support them—can be scrutinized (Mohinder Singh Gill v. Chief Election Commissioner, 1978).

Additionally, courts retain limited power to step in under extraordinary circumstances where arbitrary executive conduct threatens electoral fairness, though such intervention is sparingly exercised to prevent delays and preserve the integrity and timeliness of elections.

Still Relevant Today

This principle is still the law of the land. Many later court decisions have confirmed it. The Election Commission of India also relies on this rule to stop any legal interference while an election is actively going on, ensuring the process runs smoothly for everyone.

This rule has been repeatedly upheld, including in recent years when the Election Commission invoked Article 329(b) to resist mid-election legal challenges—such as in the 2019 and 2024 Lok Sabha elections, notably when it successfully cited the provision before the Supreme Court in May 2024 during the hearing of an interim application by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) in a pending 2019 petition, seeking immediate publication of booth-wise voter turnout data and scanned copies of Form 17C records after each phase of polling; the Court (Justices Dipankar Datta and Satish Chandra Sharma) adjourned the matter post-election, refusing interim relief on the ground that judicial interference was barred under Article 329(b) during the ongoing electoral process, describing it as a “hands-off” approach to prevent disruption.

Conclusion

The landmark Ponnuswami judgment solidified a crucial principle for Indian democracy by ensuring elections run smoothly and conclude on time, without judicial interruptions during the process under Article 329(b) of the Constitution and Section 80 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. This approach, aimed at preventing disorder, delays, and uncertainty, emphasizes the electoral system’s efficiency, timely results, and national priorities over individual disputes during voting. By directing all challenges to be resolved post-election through specialized High Courts, it reinforces the fairness and integrity of elections, safeguarding democracy’s core values—a framework that remains critically upheld in modern times.