Introduction

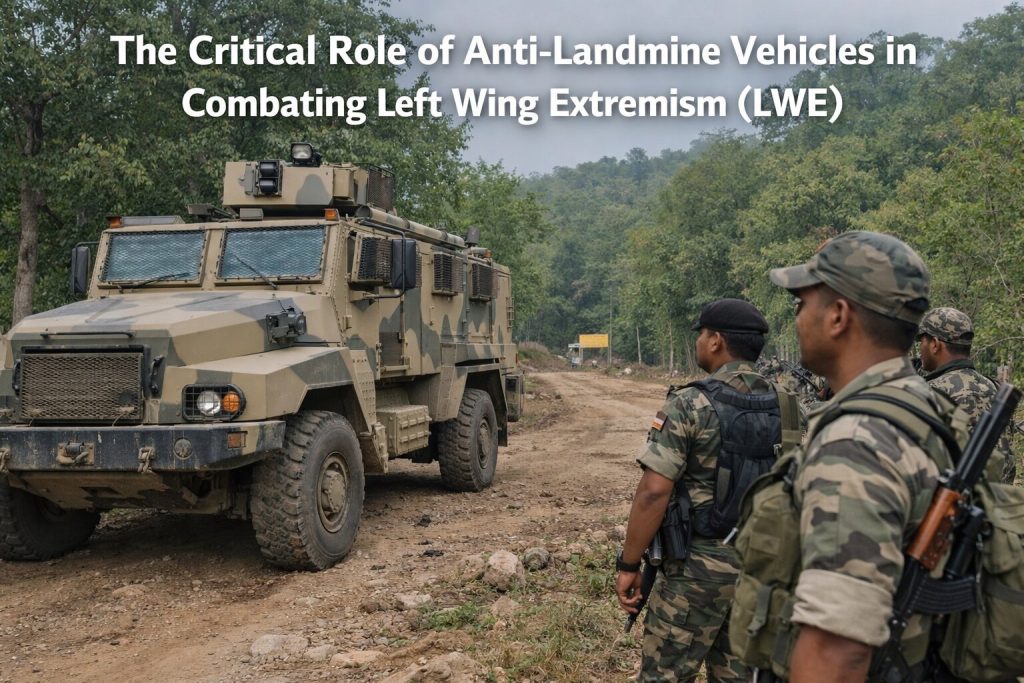

Left Wing Extremism (LWE), often referred to as the Naxalite–Maoist insurgency in India, has posed one of the most enduring internal security challenges for the nation. Rooted in socio-economic grievances and armed struggle, LWE’s operational dynamics have evolved into asymmetric warfare, relying heavily on guerrilla tactics such as improvised explosive devices (IEDs), landmines, ambushes, and hit-and-run attacks. In this theatre, anti-landmine vehicles — also known as Mine-Protected Vehicles (MPVs) or Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles — have emerged as essential tools for enhancing the survivability of security forces and maintaining operational momentum.

This article explores why anti-landmine vehicles are important in the LWE fight, their operational impact, design principles, challenges, limitations, and how they fit into broader counter-insurgency doctrine.

Left Wing Extremism: A Persistent Insurgency

What is Left Wing Extremism?

Left Wing Extremism in India refers to the armed struggle led by groups espousing Maoist ideology. These organisations operate primarily in forested and rural districts spread across several states — including Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar, and Andhra Pradesh/Telangana — where they have sought to undermine state authority through violence, subversion, and mass mobilisation.

The insurgents have developed sophisticated tactics that aim to exploit the strengths of the terrain and strategic vulnerabilities of conventional forces. IEDs and landmines have become among their most potent tools, enabling small groups of cadres to inflict maximum damage with minimal personnel losses.(India Blooms)

The Threat of Landmines and IEDs in LWE

- The Nature of the Explosive Threat

One of the defining features of LWE’s operational strategy has been the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), landmines, and other explosive traps. Rather than confronting security forces directly, insurgents often:

- Plant IEDs and pressure-activated devices along patrol routes.

- Conceal explosive charges deep underground or under dense foliage.

- Trigger explosions remotely or through victim-operated mechanisms.

These devices are typically built from locally available materials — fertilisers, gelatine sticks, emulsions, slurries, and homemade explosive mixtures — which allow cadres to construct powerful charges capable of severe destruction.(India Blooms)

The lethality of these devices was brought into sharp focus in incidents such as the 2018 Sukma attack, where a mine-protected vehicle was destroyed by an IED, resulting in nine fatalities among security personnel.(Wikipedia)

- Operational Impact of Explosive Devices

The strategic use of these explosives has profound implications:

- Slows down troop movement and patrols because every road and trail becomes suspect.

- Inflicts casualties and demoralises forces.

- Diverts resources to detection and clearance tasks.

- Disrupts civil-military operations by making travel unsafe.

Indeed, explosive devices often serve as the initial shock element in Maoist ambushes, softening convoys or patrols before further attack, thereby maximising insurgent effectiveness and minimising their own risk.(Eurasia Review)

Anti-Landmine Vehicles: An Overview

What Are Anti-Landmine Vehicles?

Anti-landmine vehicles — typically referred to as Mine-Protected Vehicles (MPVs) or MRAPs (Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected) — are specially designed to protect occupants from explosive blasts originating from landmines or IEDs. Key design features often include:

- V-shaped hulls that help deflect blast forces away from occupants.

- Armoured bodywork that protects against small arms fire and fragmentation.

- Reinforced floors and suspension systems to absorb blast impact.

- Blast-resistant seating and energy-absorbing cabin designs.

These vehicles are intended to navigate hostile terrain while offering maximum survivability for personnel inside.

The Strategic Importance of Anti-Landmine Vehicles

Enhancing Personnel Survivability

The primary objective of anti-landmine vehicles is to save lives. Traditional vehicles — wheeled transports, jeeps, or soft-skin trucks — offer little protection against blast effects. MPVs reduce:

- Immediate blast injuries by diverting explosive force.

- Secondary injuries from vehicle rollover or fragmentation.

- Lethality from small arms fire during follow-on ambushes.

Even when an MPV is damaged or disabled, the likelihood of occupants surviving is significantly higher than in unprotected vehicles. This has critical implications for morale and operational continuity among security personnel.

Operational Freedom and Mobility

Security forces in LWE-affected zones must sustain mobility to conduct area domination operations, cordon-and-search missions, long-range patrols, and rapid response tasks. Anti-landmine vehicles:

- Enable safer convoy movement along suspect routes.

- Facilitate troop ingress and casualty extraction under threat.

- Provide mobile command and control platforms in volatile terrain.

Without such vehicles, forces may be forced to move on foot or rely on less protective transport, slowing operations and increasing exposure to risk.

Psychological and Deterrence Value

Possessing vehicles that can withstand explosive attacks offers a psychological edge:

- For security forces: confidence that they have better tools to mitigate risk.

- For adversaries: a signal that their cheap explosive tactics may not guarantee success.

Even where insurgents escalate explosive weight to defeat armour, the knowledge that forces deploy armoured assets influences tactical decisions and resource allocation for all sides.

Enabling Civilian Protection and Reconstruction

Beyond combat operations, MPVs are important in:

- Escorting development convoys and infrastructure work teams.

- Facilitating relief and humanitarian missions.

- Protecting officials and civilians in volatile regions.

In areas where insurgent explosive threats target both security and civilian traffic, MPVs can provide safe mobility corridors that support governance and development efforts.

Examples of Anti-Landmine Vehicles in the Indian Context

- Mahindra Mine Protected Vehicle (MPV-I)

Developed jointly by Mahindra & Mahindra and BAE Systems, the Mahindra MPV-I was designed for counter-insurgency missions, featuring a V-hull and armour capable of withstanding significant blast effects. It held the capacity for 18 personnel and offered protection against small arms fire and landmine threats.(Wikipedia)

However, the vehicle could only withstand limited explosive weights, leading to its restricted operational role. It was primarily used for troop movement or casualty evacuation rather than routine patrolling after insurgents countered its protection levels.(Wikipedia)

- Ordnance Factory Board’s Aditya MPV

The Aditya MPV, based on the Casspir Mk II design, has been another key vehicle used by the Indian Army and Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) for troop transport with blast protection. Enhanced versions sought to improve blast resistance and integrate remote weapon stations.(Wikipedia)

- Other Armoured Vehicles

India also employs light armoured carriers — such as the Tata Light Armoured Troop Carrier (LATC) — which provide ballistic and some blast protection, though not always at the same level as dedicated MRAPs. These vehicles are used for troop transport and internal security tasks in dangerous zones.(Wikipedia)

Debates and Limitations

Are MPVs Always Effective?

There has been considerable debate within the security establishment about the utility of anti-landmine vehicles in the LWE context:

- Blast Limitations: Many MPVs are designed to withstand blasts equivalent to conventional military mines (e.g., up to 14 kg of TNT). However, Maoists often construct IEDs with higher explosive weights that can exceed these thresholds.(claws.co.in)

- Operational Surprises: In several instances, even armoured vehicles have been destroyed by powerful IEDs, leading to fatalities among personnel.(Wikipedia)

The result is a paradox: while MPVs offer improved survivability, they cannot guarantee safety against all weapon configurations. Some commanders have therefore chosen to limit their use on foot patrols, emphasising terrain familiarity and traditional infantry tactics in dense jungle. (Millennium Post)

Cost, Maintenance, and Logistics

Anti-landmine vehicles are expensive to procure and maintain. Budget constraints and logistical complexities — from spare parts to trained drivers — affect deployment rates and operational reach. The Indian security forces historically faced shortfalls between the number of sanctioned MPVs and actual deployments in the field.(India Today)

Terrain Challenges

LWE areas often include rugged forests, narrow trails, and uneven terrain that challenge heavy armoured vehicles. In such environments:

- Foot patrols may be more flexible and less detectable.

- Heavy MPVs could be restricted to main roads, limiting flexibility.

This necessitates a combined approach — merging the mobility of foot patrols with the protective advantages of vehicles.

Integrating Anti-Landmine Vehicles into Counter-Insurgency Doctrine

Combined Arms and Multi-Layered Approach

A robust counter-insurgency strategy does not rely solely on MPVs. It integrates:

- Infantry patrols and jungle warfare units (e.g., specialised forces like the Greyhounds).

- Intelligence-led operations.

- IED detection and clearance equipment.

- Air surveillance and rapid response teams.

In this model, MPVs become one component in a larger toolkit that supports safe movement, area control, and quick reaction.

Detection Technologies

Because anti-landmine vehicles alone cannot eliminate the threat of explosives, investments in detection technologies — remote sensing, ground-penetrating radar, robotic scouts — are critical complements. Detection allows forces to identify IEDs before they trigger blasts.

Looking Ahead: Future of Anti-Landmine Vehicles in LWE Fight

- Improved Blast Resistance and Modular Designs

Future designs may incorporate enhanced blast resistance, lighter materials, and modular armour kits that adapt to threat levels. This would improve survivability without excessive weight penalties.

- Autonomous and Remote Platforms

Unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) equipped with detection sensors could precede convoys, identifying and neutralising threats without risking personnel. Although still in development phases globally, such platforms could transform how insurgent explosive threats are countered.

- Better Battlefield Data and Training

Enhanced data collection — from IED incidents to blast effects — can help refine vehicle design and tactical use. Training crews on explosive threat patterns and counter-IED tactics will remain essential.

Limitations of Anti-Landmine Vehicles in Countering Left-Wing Extremism

Anti-landmine vehicles (ALMVs) were introduced to enhance the survivability of security forces against landmines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), a preferred weapon of Left-Wing Extremist (LWE) groups. However, their protection is inherently limited by design thresholds. Most ALMVs are engineered to withstand only a specified explosive weight, whereas LWE cadres frequently employ high-yield, deep-buried, or shaped IEDs that exceed these limits. When such devices are detonated, even armoured vehicles can suffer catastrophic damage, leading to fatalities. This limitation creates a constant cycle of adaptation, where insurgents escalate explosive power to neutralise armoured advantages. Consequently, ALMVs reduce risk but cannot guarantee safety, making them a partial solution rather than a fail-safe counter to the explosive threat.

Another major constraint lies in terrain and mobility. LWE-affected regions are characterised by dense forests, narrow dirt tracks, steep gradients, and poor infrastructure. Heavy anti-landmine vehicles struggle to manoeuvre in such environments and are largely confined to predictable road networks. This restriction increases operational predictability, allowing insurgents to pre-survey routes and establish ambush sites. Moreover, the size and noise of these vehicles reduce stealth and surprise, which are critical elements in counter-insurgency operations. Over-reliance on ALMVs can also lead to a decline in foot patrols and jungle warfare skills, creating a false sense of security and tactical complacency among troops. Thus, while offering protection, ALMVs may inadvertently narrow operational flexibility.

Finally, anti-landmine vehicles face economic, logistical, and doctrinal limitations. They are expensive to procure, maintain, and repair, requiring specialised training, spare parts, and infrastructure that many state police forces lack. Even when deployed, ALMVs do not detect explosives on their own and depend heavily on intelligence inputs, route sanitisation, and counter-IED measures. A vehicle immobilised after a blast can expose troops to secondary ambushes and complicate rescue or recovery operations. More importantly, ALMVs cannot address the root causes of LWE, such as governance deficits, lack of development, and local alienation. Therefore, their role must remain supportive within a broader counter-insurgency strategy that prioritises intelligence-led operations, foot-based mobility, and socio-economic interventions alongside limited and judicious use of armour.

Conclusion

The war against Left Wing Extremism represents a protracted battle between state security forces and insurgents who exploit asymmetric tactics — including IEDs and landmines. In this environment, anti-landmine vehicles serve as an indispensable asset, offering enhanced survivability, operational freedom, and psychological confidence for security forces navigating deadly territories.

While not a standalone solution — and despite limitations when facing high-yield IEDs — MPVs continue to play a vital role in reducing casualties, maintaining mobility, and supporting development and governance initiatives in LWE-affected regions. As technologies evolve and doctrines adapt, anti-landmine vehicles will remain a cornerstone of India’s internal security apparatus in combating one of its most resilient insurgencies.