Introduction: The Legal Context of Jurisdictional Boundaries and Parallel Proceedings

The Indian legal system operates on a well-established hierarchy of courts and tribunals, each with defined jurisdictional boundaries. This hierarchical structure is designed to ensure orderly administration of justice, prevent conflicting decisions, and maintain the rule of law. However, one of the persistent challenges faced by the government and its various authorities is the issue of parallel proceedings—where the same dispute is simultaneously pursued before multiple forums. This practice not only burdens the judicial system but also creates confusion, delays justice, and potentially leads to contradictory orders.

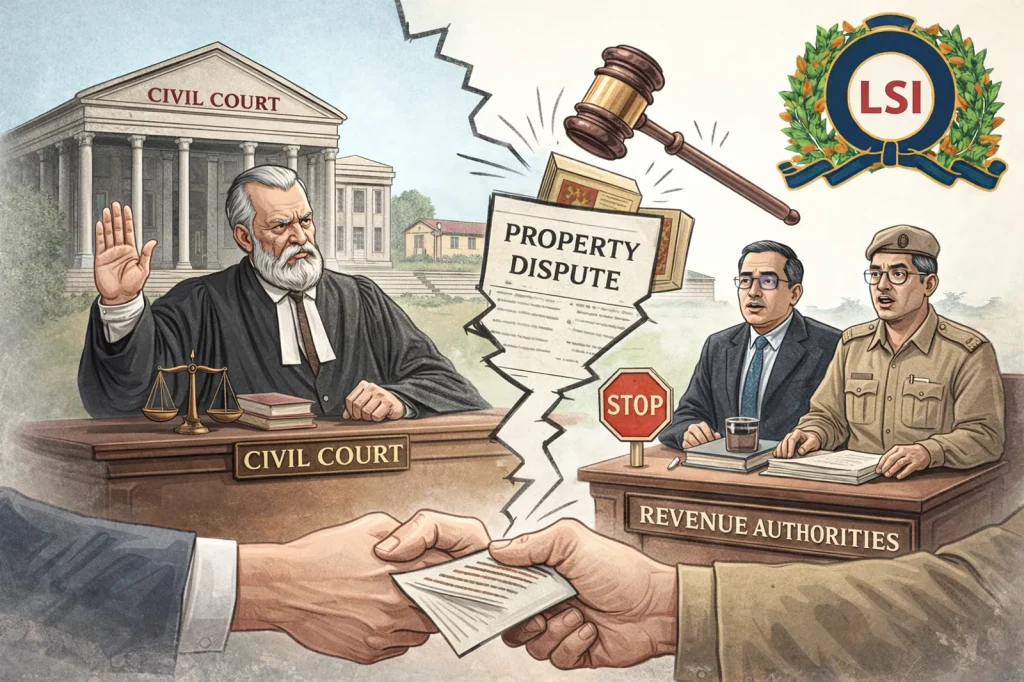

The recent judgment by the Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh High Court in Farooq Ahmad Shiekh v. Financial Commissioner (WP(C) No. 3035/2025) brings to the forefront a critical aspect of administrative law: the relationship between civil courts and revenue authorities, and the challenges government authorities face when litigants attempt to circumvent established legal procedures. Justice Wasim Sadiq Nargal’s bench not only dismissed the petition but also imposed exemplary costs of Rs 50,000 on the petitioners for suppressing material facts and engaging in forum shopping.

The principle that civil courts possess superior jurisdiction over revenue authorities in matters involving property disputes and civil rights is well-established in Indian jurisprudence. This doctrine stems from the constitutional framework that guarantees access to justice and ensures that specialized tribunals and administrative authorities do not encroach upon the domain of civil courts. The civil court’s jurisdiction is plenary in nature, meaning it has the power to adjudicate all civil disputes unless expressly barred by statute. Revenue authorities, on the other hand, derive their powers from specific statutes and are generally limited to administrative and revenue-related matters.

The challenge for government authorities, particularly revenue officials, lies in navigating this complex jurisdictional landscape. When a dispute is already pending before a civil court, revenue authorities are expected to exercise restraint and refrain from adjudicating the same matter. This principle, often referred to as the doctrine against parallel proceedings, serves multiple purposes: it prevents conflicting judgments, respects the hierarchy of courts, conserves judicial resources, and protects litigants from the harassment of multiple proceedings.

However, the practical implementation of this principle presents several challenges for government authorities. First, there is often a lack of coordination between different forums, making it difficult for revenue authorities to ascertain whether a matter is already sub judice before a civil court. Second, litigants may deliberately suppress information about pending civil proceedings to obtain favorable orders from revenue authorities. Third, the boundaries between purely revenue matters and civil disputes are not always clear-cut, creating genuine confusion about which forum has jurisdiction.

The J&K and Ladakh High Court’s judgment addresses these challenges head-on by reaffirming that revenue authorities must “lay their hands off” when the same controversy is pending before a civil court. This strong language underscores the court’s concern about the proliferation of parallel proceedings and the need for strict adherence to jurisdictional principles. The imposition of costs further signals that courts will not tolerate attempts to manipulate the legal system through suppression of material facts or forum shopping.

This case also highlights the broader challenge faced by government authorities in maintaining the integrity of the legal process while ensuring efficient dispute resolution. Revenue authorities are often the first point of contact for citizens seeking redressal of grievances related to land, property, and public infrastructure. They must balance their duty to provide accessible justice with the need to respect the superior jurisdiction of civil courts. This requires not only legal acumen but also institutional mechanisms for information sharing and coordination between different forums.

The judgment has significant implications for administrative law practice in India. It reinforces the principle that equitable relief cannot be obtained through fraudulent suppression of facts or by circumventing established legal procedures. The court’s observation that “what the petitioners could not achieve directly is being achieved by fraud and indirectly by suppressing material facts” reflects a fundamental principle of equity jurisprudence: he who comes to equity must come with clean hands. This principle is particularly relevant in the context of government litigation, where public authorities must ensure that their actions are not only legally sound but also procedurally fair.

Case Background: Facts, Parties, and Legal Questions

The case of Farooq Ahmad Shiekh v. Financial Commissioner arose from a dispute over a public link road in Kupwara district of Jammu & Kashmir. The factual matrix of the case reveals a complex web of proceedings before multiple forums, ultimately leading to the High Court’s intervention and its strong observations on the conduct of the petitioners and the role of revenue authorities.

The dispute originated when private respondents filed an application before the Deputy Commissioner, Kupwara, seeking the removal of obstruction and encroachment on a public link road that had been constructed by the Rural Development Department. The complainants alleged that certain individuals, who later became the petitioners in the writ petition, had obstructed the public pathway, thereby preventing the community from accessing this essential infrastructure. The Deputy Commissioner, exercising his administrative powers under the revenue laws, directed the Tehsildar Lalpora to visit the spot, conduct an inspection, and remove the obstruction or encroachment in accordance with the law.

This order of the Deputy Commissioner was challenged by the petitioners through an appeal before the Divisional Commissioner, Kashmir. However, the matter was transferred to the Additional Commissioner, Kashmir, who had been delegated the powers of the Divisional Commissioner for the purpose of deciding such appeals. After examining the facts and hearing the parties, the Additional Commissioner dismissed the appeal, thereby upholding the order of the Deputy Commissioner directing the removal of the obstruction.

Dissatisfied with this outcome, the petitioners filed a revision petition before the Financial Commissioner, which is the highest revenue authority in the erstwhile state of Jammu & Kashmir (now Union Territory). The Financial Commissioner, after considering the submissions and examining the record, also dismissed the revision petition and upheld the concurrent findings of the Deputy Commissioner and the Additional Commissioner. Having exhausted the remedies available within the revenue hierarchy, the petitioners then approached the High Court of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh by filing a writ petition under Article 226 of the Constitution of India.

However, what the petitioners failed to disclose to the revenue authorities and initially to the High Court was a crucial fact: the same dispute regarding the pathway was already pending before the civil court. The private respondents had filed a civil suit before the Munsiff Court, Sogam, seeking a declaration of their rights over the pathway and an injunction restraining the petitioners from interfering with or encroaching upon the said pathway. More significantly, the civil court had already passed an interim order restraining the petitioners from causing any interference with or making any encroachment upon the pathway in question.

This suppression of material facts became the central issue in the High Court proceedings. The Bench, presided over by Justice Wasim Sadiq Nargal, took serious note of the fact that the petitioners were fully aware of the civil proceedings and the restraint order passed by the civil court, yet they chose to pursue parallel proceedings before the revenue authorities. The petitioners did not challenge the civil court’s order before the appropriate appellate forum, which would have been the District Court. Instead, they attempted to obtain relief from the revenue authorities on the same issue, hoping for a favorable outcome that would effectively nullify the civil court’s order.

The legal questions that arose before the High Court were multifaceted and touched upon fundamental principles of administrative law, civil procedure, and equity jurisprudence. The primary question was whether revenue authorities have the jurisdiction to adjudicate a dispute when the same matter is already pending before a civil court and when the civil court has already passed an interim order on the subject matter of the dispute. This question goes to the heart of the relationship between civil courts and revenue tribunals in the Indian legal system.

The second question was whether the petitioners’ conduct in suppressing the fact of pending civil proceedings and the restraint order passed by the civil court amounted to an abuse of the legal process. This question raised issues of procedural propriety, good faith litigation, and the equitable principle that parties must approach courts with clean hands. The High Court had to consider whether such conduct warranted not only dismissal of the petition but also the imposition of costs as a deterrent against forum shopping and suppression of material facts.

The third question was whether the revenue authorities should have exercised restraint and declined to adjudicate the matter once they became aware (or should have been aware) that the same dispute was pending before a civil court. This question highlighted the challenges faced by government authorities in maintaining jurisdictional discipline and the need for institutional mechanisms to prevent parallel proceedings.

The parties to the dispute were represented by senior legal counsel. Senior Advocate R. A. Jan, along with Advocate Syed Yahya, appeared for the petitioners (appellants), while Government Advocate Faheem Nissar Shah, along with Advocates Sheikh Manzoor and Ruaani Ahmad Baba, represented the respondents. The presence of senior counsel on both sides underscored the importance of the legal issues involved and the potential precedential value of the judgment.

The factual background also revealed the practical challenges faced by government authorities in dealing with disputes over public infrastructure. The public link road in question had been constructed by the Rural Development Department, presumably using public funds and for the benefit of the community. The obstruction of such a public pathway not only affected the rights of individual citizens but also implicated broader public interest considerations. The Deputy Commissioner, as the chief administrative officer of the district, had a duty to ensure that public infrastructure remained accessible and that encroachments were removed in accordance with the law.

However, the existence of a civil suit and a restraint order from the civil court complicated the administrative response. The revenue authorities found themselves caught between their duty to protect public property and remove encroachments on one hand, and the need to respect the civil court’s jurisdiction and orders on the other. This dilemma illustrates the broader challenge faced by government authorities in coordinating their actions with judicial proceedings and ensuring that administrative actions do not conflict with court orders.

The case also highlighted the issue of remedies available to parties aggrieved by orders of revenue authorities. The petitioners had pursued appeals through the revenue hierarchy—from the Deputy Commissioner to the Additional Commissioner to the Financial Commissioner—before approaching the High Court. This exhaustion of alternative remedies is generally a prerequisite for invoking the extraordinary writ jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226. However, the High Court’s judgment made it clear that even after exhausting such remedies, parties cannot circumvent the civil court’s jurisdiction by seeking relief from revenue authorities on matters already sub judice before civil courts.

Court’s Observations: Judicial Reasoning and Legal Significance

The judgment delivered by Justice Wasim Sadiq Nargal of the Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh High Court is notable for its clear articulation of fundamental principles governing the relationship between civil courts and revenue authorities, and for its strong observations on the conduct expected of litigants approaching courts for equitable relief. The court’s reasoning addresses both the substantive legal issues and the procedural impropriety demonstrated by the petitioners.

The court began its analysis by examining the factual matrix and immediately identified the critical flaw in the petitioners’ approach: the suppression of the fact that the same dispute was already pending before the Munsiff Court, Sogam, and that the civil court had already passed a restraint order. The Bench observed that “the matter was pending before the Civil Court and the Civil Court had already passed a restraint order, whereby the petitioners were prohibited from causing any interference with, or making any encroachment upon, the said pathway.” This observation established the foundation for the court’s subsequent reasoning on parallel proceedings and jurisdictional propriety.

The High Court emphasized that once a civil court passes an order, particularly a restraint order, it becomes incumbent upon all parties to adhere to it and pursue any grievance arising therefrom before the appropriate appellate court. The court noted that the petitioners were in “active knowledge” of the civil court’s order, yet they chose not to challenge it before the superior court through the proper appellate mechanism. Instead, they pursued parallel proceedings before the revenue authorities, hoping to obtain a favorable outcome that would effectively circumvent the civil court’s order.

The court’s most significant legal observation came in the form of a categorical statement on the principle against parallel proceedings: “This Court is of the considered view that once a Civil Court had taken cognizance of the dispute, the petitioners by no stretch of imagination can have parallel proceedings simultaneously for the same issue before another authority.” This unequivocal language leaves no room for ambiguity and establishes a clear rule that parties cannot pursue the same dispute before multiple forums simultaneously.

Building on this principle, the court articulated the doctrine of civil court supremacy in matters involving civil disputes: “It is well settled that the jurisdiction of Civil Court is superior and revenue authorities cannot adjudicate upon such issues when the same are already before a Civil Court.” This statement reaffirms the constitutional and statutory framework that recognizes the plenary jurisdiction of civil courts and the limited, specialized jurisdiction of revenue authorities. The court’s use of the phrase “well settled” indicates that this is not a novel principle but rather a long-established doctrine of Indian jurisprudence.

The court then addressed the specific obligations of revenue authorities when faced with disputes that are already pending before civil courts: “The principle against parallel proceedings is settled and revenue authorities are expected to lay their hands off when the same controversy is pending before the Civil Court.” The phrase “lay their hands off” is particularly striking and conveys the court’s expectation that revenue authorities should exercise restraint and defer to the civil court’s jurisdiction. This observation directly addresses the challenges faced by government authorities and provides clear guidance on how they should respond when confronted with such situations.

From a critical perspective, this observation is significant because it places an affirmative duty on revenue authorities to ascertain whether a matter is already pending before a civil court before proceeding to adjudicate it. This implies that revenue authorities cannot simply rely on the information provided by the parties but must conduct due diligence to ensure that they are not encroaching upon the civil court’s jurisdiction. However, the judgment does not elaborate on the practical mechanisms through which revenue authorities should obtain such information, which could be a potential gap in implementation.

The court’s analysis of the petitioners’ conduct was particularly scathing. The Bench observed that the petitioners “did not challenge the same before the superior court. Instead of availing the remedy available before the appropriate court, the petitioners challenged all the orders passed by the revenue authorities before this court.” The court characterized this approach as a failure to follow “the settled legal process” and an attempt to “pursue the same issue before different forums and ultimately before this court by way of the instant petition.”

This observation highlights a common problem in Indian litigation: forum shopping and the strategic use of multiple proceedings to delay justice or obtain favorable outcomes. The court’s criticism of this practice is rooted in the principle of procedural fairness and the efficient administration of justice. When parties pursue parallel proceedings, they not only waste judicial resources but also create the risk of conflicting decisions, which undermines the coherence and predictability of the legal system.

The court then applied equitable principles to the petitioners’ conduct, stating: “What the petitioners could not achieve directly is being achieved by fraud and indirectly by suppressing material facts and this court cannot shut its eyes to such a conduct on the part of the party seeking equitable right.” The use of the word “fraud” is significant and indicates the court’s view that the suppression of material facts was not merely a procedural irregularity but a deliberate attempt to mislead the court and obtain relief through deception.

The court invoked the maxim “he who comes to equity must come with clean hands,” stating: “Law of equity does not permit a party to secure indirectly what it is prohibited from claiming directly.” This principle is fundamental to equity jurisprudence and reflects the idea that courts will not assist parties who engage in dishonest or improper conduct. By applying this principle, the court sent a strong message that litigants who suppress material facts or engage in forum shopping will not receive the court’s assistance, regardless of the merits of their underlying claim.

From a legal significance perspective, this aspect of the judgment is crucial because it reinforces the ethical obligations of litigants and their counsel. In an adversarial system, parties are expected to present their case in the best possible light, but this does not extend to suppressing material facts or misleading the court. The judgment serves as a reminder that procedural propriety and good faith are essential components of access to justice.

The court also criticized the revenue authorities for proceeding with the matter despite the pendency of the civil suit. The Bench noted that “the revenue authorities should not have proceeded with the same issue which was the subject matter of the civil suit that was pending before the Munsiff Court Sogam.” This observation places responsibility not only on the litigants but also on the government authorities to maintain jurisdictional discipline. It suggests that revenue authorities have an independent obligation to ensure that they do not adjudicate matters that are already before civil courts, even if the parties do not disclose such information.

This aspect of the judgment raises important questions about the institutional capacity of revenue authorities to identify and avoid parallel proceedings. In practice, revenue authorities may not have easy access to information about pending civil suits, especially in jurisdictions where case management systems are not fully integrated. The judgment implicitly calls for better coordination and information sharing between different forums to prevent such situations.

To deprecate the practice of suppressing material facts and pursuing parallel proceedings, the court imposed exemplary costs of Rs 50,000 on the petitioners. The imposition of costs serves multiple purposes: it compensates the respondents for the unnecessary litigation, deters other litigants from engaging in similar conduct, and signals the court’s disapproval of procedural impropriety. The quantum of costs, while not extraordinarily high, is significant enough to serve as a deterrent, especially in the context of a dispute over a public pathway.

The court’s decision to set aside the orders passed by the Deputy Commissioner, Additional Commissioner, and Financial Commissioner was a logical consequence of its finding that the revenue authorities should not have adjudicated the matter in the first place. By setting aside these orders, the court effectively restored the status quo ante and ensured that the civil court’s jurisdiction was not undermined by parallel proceedings before revenue authorities.

From a broader perspective, the judgment reflects the judiciary’s concern about the proliferation of litigation and the need for stricter enforcement of procedural discipline. The strong language used by the court and the imposition of costs indicate a shift towards a more proactive approach in dealing with abuse of process. This approach is consistent with recent trends in Indian jurisprudence, where courts have increasingly been willing to impose costs and sanctions to deter frivolous litigation and forum shopping.

Impact: Broader Legal and Practical Implications

The judgment in Farooq Ahmad Shiekh v. Financial Commissioner has far-reaching implications for administrative law, civil procedure, and the relationship between different forums in the Indian legal system. The decision addresses fundamental questions about jurisdictional boundaries, the conduct expected of litigants, and the challenges faced by government authorities in maintaining the integrity of the legal process. The impact of this judgment extends beyond the immediate parties and has the potential to influence litigation strategy, administrative practice, and judicial approach to parallel proceedings across India.

Impact on Revenue Authorities and Administrative Practice

One of the most significant impacts of this judgment is on the functioning of revenue authorities across India, particularly in states and union territories where revenue administration plays a crucial role in dispute resolution. The court’s categorical statement that revenue authorities must “lay their hands off” when a matter is pending before a civil court establishes a clear protocol that revenue officials must follow. This has several practical implications for government authorities.

First, revenue authorities will need to develop institutional mechanisms to ascertain whether a dispute brought before them is already pending before a civil court. This may require the establishment of coordination protocols between revenue departments and civil courts, possibly through integrated case management systems or mandatory disclosure requirements for parties approaching revenue authorities. The judgment implicitly places a burden on revenue authorities to conduct due diligence before adjudicating disputes, which may require additional resources and training for revenue officials.

Second, the judgment provides revenue authorities with a legal basis to decline jurisdiction when they discover that a matter is already sub judice before a civil court. This can help revenue officials avoid the difficult position of being caught between their administrative duties and the need to respect civil court jurisdiction. By clearly articulating the principle of civil court supremacy, the judgment empowers revenue authorities to defer to civil courts without appearing to shirk their responsibilities.

Third, the judgment may lead to a more cautious approach by revenue authorities in entertaining applications for removal of encroachments or obstructions, particularly in cases involving disputed property rights. Revenue officials may now require parties to provide affidavits or declarations stating that the matter is not pending before any civil court, thereby shifting some of the burden of disclosure onto the parties themselves. This could help protect revenue authorities from criticism or legal challenges based on jurisdictional overreach.

However, the judgment also highlights a potential challenge for government authorities: the need to balance their duty to protect public property and remove encroachments with the requirement to respect civil court jurisdiction. In cases involving public infrastructure, such as roads, pathways, or government land, revenue authorities have a legitimate interest in ensuring that public property is not unlawfully occupied or obstructed. The judgment does not suggest that revenue authorities should completely abdicate their responsibilities in such matters, but rather that they should exercise restraint when the same dispute is already before a civil court.

Impact on Litigants and Litigation Strategy

For litigants, particularly those involved in property disputes or conflicts with government authorities, this judgment sends a clear message about the consequences of forum shopping and suppression of material facts. The imposition of Rs 50,000 in costs, while not extraordinarily high, is significant enough to deter parties from pursuing parallel proceedings or concealing information about pending cases. This may lead to more transparent and honest disclosure practices by litigants and their counsel.

The judgment also clarifies the remedies available to parties aggrieved by orders of revenue authorities. While parties can pursue appeals through the revenue hierarchy and ultimately approach the High Court through writ jurisdiction, they cannot use these remedies to circumvent or undermine orders passed by civil courts. This means that litigants must carefully consider their forum selection at the outset of a dispute and pursue their claims through the appropriate channel.

From a strategic perspective, the judgment reinforces the importance of choosing the right forum at the beginning of a dispute. Parties who file civil suits will now have stronger grounds to object if the opposing party attempts to pursue parallel proceedings before revenue authorities. The judgment provides a clear legal basis for seeking the dismissal or stay of such parallel proceedings, which can help prevent the harassment and delay that often result from multiple proceedings on the same issue.

The judgment also has implications for legal practitioners, who have an ethical obligation to advise their clients about pending proceedings and to avoid suppressing material facts before courts or tribunals. Lawyers who assist clients in pursuing parallel proceedings or concealing information about pending cases may face professional consequences, including potential disciplinary action by bar councils. The judgment serves as a reminder that the duty of candor to the court is paramount and that short-term tactical advantages gained through suppression of facts can lead to long-term consequences, including costs and adverse findings.

Impact on Civil Courts and Judicial Administration

For civil courts, this judgment reinforces their superior jurisdiction in matters involving civil disputes and property rights. The clear articulation of the principle that revenue authorities cannot adjudicate disputes already pending before civil courts strengthens the authority of civil courts and reduces the risk of conflicting decisions. This can contribute to greater coherence and predictability in the legal system, which benefits all stakeholders.

The judgment also has implications for case management practices in civil courts. Courts may now be more vigilant in monitoring whether parties are pursuing parallel proceedings before other forums and may be more willing to impose costs or sanctions when such conduct is discovered. This could lead to more proactive case management, with courts requiring parties to disclose any related proceedings before other forums as part of the pleadings or during case management conferences.

The decision may also influence the approach of appellate courts when reviewing orders passed by revenue authorities. Appellate courts may now be more likely to set aside orders of revenue authorities if they find that the matter was already pending before a civil court at the time the revenue authority adjudicated it. This could lead to a more robust enforcement of jurisdictional boundaries and a clearer delineation of the respective roles of civil courts and revenue authorities.

Impact on the Doctrine Against Parallel Proceedings

This judgment contributes to the evolving jurisprudence on parallel proceedings in India. While the principle against parallel proceedings has been recognized in various contexts, this judgment provides a clear and forceful articulation of the principle in the specific context of civil courts and revenue authorities. The court’s use of strong language—”by no stretch of imagination”—leaves little room for exceptions or qualifications, which may influence how other courts approach similar issues.

The judgment also clarifies that the doctrine against parallel proceedings applies not only when identical proceedings are pending but also when the same controversy or subject matter is being litigated in different forums. This broader interpretation of the doctrine can help prevent parties from attempting to circumvent the principle by framing their claims differently in different forums while essentially seeking relief on the same underlying dispute.

From a comparative perspective, the judgment aligns with the approach taken by courts in other common law jurisdictions, where the doctrine of lis pendens (pending suit) and principles of comity between courts are well-established. The judgment reinforces the idea that judicial resources should be conserved and that parties should not be allowed to engage in forum shopping or pursue multiple proceedings on the same issue.

Impact on Public Interest and Access to Justice

The judgment also has implications for public interest considerations, particularly in cases involving public infrastructure and community resources. The dispute in this case involved a public link road constructed by the Rural Development Department, which presumably served the needs of the local community. The obstruction of such a pathway affected not only the immediate parties but also the broader public interest in maintaining access to public infrastructure.

By setting aside the orders of the revenue authorities and effectively restoring the civil court’s exclusive jurisdiction over the dispute, the judgment ensures that such matters are decided through a more formal and rigorous judicial process. Civil courts, with their established procedures for evidence, cross-examination, and reasoned decision-making, may be better equipped to balance the competing interests of individual property rights and public access to infrastructure.

However, the judgment also raises questions about access to justice, particularly for parties who may find civil court proceedings more expensive, time-consuming, and complex than administrative proceedings before revenue authorities. Revenue authorities often provide a more accessible and informal forum for dispute resolution, especially in rural areas where civil courts may be distant or overburdened. The judgment’s emphasis on civil court supremacy may inadvertently create barriers to access for some parties, particularly those with limited resources or legal sophistication.

This tension between jurisdictional propriety and access to justice is a recurring theme in administrative law and highlights the need for a balanced approach. While the principle against parallel proceedings is important for maintaining the integrity of the legal system, it should not be applied in a manner that denies parties effective remedies or forces them to navigate complex and expensive judicial processes for relatively straightforward disputes.

Impact on Legal Technology and Case Management

The judgment also has implications for the role of legal technology in preventing parallel proceedings and improving coordination between different forums. The challenges identified in this case—lack of information sharing between civil courts and revenue authorities, difficulty in ascertaining whether a matter is already sub judice, and the potential for parties to suppress material facts—could be addressed through better use of technology.

Integrated case management systems that allow different forums to access information about pending cases could help prevent parallel proceedings. Such systems could enable revenue authorities to check whether a dispute is already pending before a civil court before accepting jurisdiction. Similarly, civil courts could be alerted if parties are pursuing parallel proceedings before revenue authorities, allowing them to take appropriate action.

Legal technology platforms that provide comprehensive case search and tracking capabilities, such as those offered by Claw Legaltech, can play a crucial role in addressing these challenges. By providing lawyers, litigants, and government authorities with easy access to information about pending cases across different forums, such platforms can help prevent the kind of jurisdictional conflicts and parallel proceedings that gave rise to this case.

Long-term Implications for Administrative Law

In the long term, this judgment may contribute to a clearer delineation of the respective roles of civil courts and administrative tribunals in the Indian legal system. The judgment reinforces the principle that civil courts have plenary jurisdiction over civil disputes unless expressly barred by statute, and that administrative authorities should exercise restraint when matters are already before civil courts.

This principle is consistent with the constitutional framework established by Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution, which vest High Courts with supervisory jurisdiction over all courts and tribunals within their territorial jurisdiction. The judgment affirms that this supervisory jurisdiction extends to ensuring that administrative authorities do not encroach upon the domain of civil courts and that jurisdictional boundaries are respected.

The judgment may also influence legislative and policy reforms aimed at improving coordination between different forums and preventing parallel proceedings. Lawmakers and policymakers may consider amendments to procedural laws or the introduction of new regulations that require parties to disclose pending proceedings before other forums and that establish protocols for coordination between civil courts and administrative authorities.

FAQs: Common Questions About Parallel Proceedings and Jurisdictional Conflicts

Q1: What are parallel proceedings, and why are they problematic?

Parallel proceedings refer to situations where the same dispute or controversy is simultaneously pursued before multiple courts, tribunals, or administrative authorities. In the context of the Farooq Ahmad Shiekh case, the petitioners were pursuing the same dispute regarding a public pathway before both the civil court (Munsiff Court, Sogam) and the revenue authorities (Deputy Commissioner, Additional Commissioner, and Financial Commissioner).

Parallel proceedings are problematic for several reasons. First, they lead to wastage of judicial and administrative resources, as multiple forums expend time and effort adjudicating the same dispute. Second, they create the risk of conflicting decisions, where different forums may reach different conclusions on the same facts and legal issues, leading to confusion and uncertainty. Third, they can be used as a dilatory tactic by parties seeking to delay the resolution of disputes or to harass the opposing party by forcing them to defend multiple proceedings simultaneously. Fourth, parallel proceedings undermine the principle of finality in litigation, as parties may continue to pursue the same issue in different forums even after one forum has decided the matter.

The J&K and Ladakh High Court’s judgment addresses these concerns by categorically stating that once a civil court has taken cognizance of a dispute, parties cannot pursue parallel proceedings before revenue authorities on the same issue. The court’s imposition of costs on the petitioners serves as a deterrent against such practices and reinforces the importance of choosing the appropriate forum at the outset of a dispute.

Q2: When should a party approach a civil court versus a revenue authority for resolving a property dispute?

The choice between approaching a civil court or a revenue authority depends on the nature of the dispute and the relief sought. Civil courts have plenary jurisdiction over all civil disputes, including those involving property rights, contracts, torts, and other civil matters. Civil courts can grant a wide range of remedies, including declarations of rights, injunctions, specific performance, damages, and other equitable relief. Civil court proceedings follow formal procedures, including pleadings, evidence, cross-examination, and reasoned judgments, which provide parties with robust procedural protections.

Revenue authorities, on the other hand, have limited jurisdiction derived from specific statutes, such as land revenue acts or tenancy laws. Revenue authorities typically deal with matters related to land records, revenue collection, mutation of property, removal of encroachments on government land, and other administrative matters. Revenue proceedings are generally more informal and expeditious than civil court proceedings, making them more accessible for certain types of disputes.

As a general rule, parties should approach civil courts when the dispute involves contested questions of title, ownership, or civil rights that require detailed examination of evidence and application of civil law principles. Revenue authorities should be approached for purely administrative or revenue-related matters that fall within their statutory jurisdiction. However, as the J&K and Ladakh High Court’s judgment makes clear, once a civil court has taken cognizance of a dispute, parties cannot pursue parallel proceedings before revenue authorities on the same issue. If a party is unsure about which forum to approach, it is advisable to consult with a legal professional who can assess the nature of the dispute and recommend the appropriate forum.

Q3: What are the consequences of suppressing material facts before a court or tribunal?

Suppressing material facts before a court or tribunal is a serious matter that can have significant legal and ethical consequences. Material facts are those facts that are relevant to the issues in dispute and that may influence the court’s decision. The duty to disclose material facts is particularly important when a party is seeking equitable relief, such as injunctions or writs, as equity requires parties to approach the court with “clean hands.”

The consequences of suppressing material facts can include: (1) Dismissal of the petition or application, as courts will not assist parties who engage in dishonest conduct; (2) Imposition of costs, as seen in the Farooq Ahmad Shiekh case where the court imposed Rs 50,000 in costs on the petitioners for suppressing the fact of pending civil proceedings; (3) Adverse inferences, where the court may draw negative conclusions about the party’s case based on the suppression; (4) Criminal prosecution in extreme cases, as suppression of material facts may amount to perjury or contempt of court; (5) Professional consequences for lawyers who assist in or fail to prevent the suppression of material facts, including potential disciplinary action by bar councils.

In the Farooq Ahmad Shiekh case, the High Court took a particularly strong view of the petitioners’ conduct in suppressing the fact that the same dispute was pending before a civil court and that the civil court had already passed a restraint order. The court characterized this conduct as an attempt to achieve “by fraud and indirectly” what the petitioners could not achieve directly, and invoked the equitable principle that parties must come to court with clean hands. This case serves as a reminder that honesty and transparency are fundamental to the administration of justice, and that parties who engage in deceptive practices will face serious consequences.

Conclusion: Future Developments and Final Thoughts

The judgment of the Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh High Court in Farooq Ahmad Shiekh v. Financial Commissioner represents a significant contribution to the jurisprudence on parallel proceedings, jurisdictional boundaries, and the ethical obligations of litigants. By clearly articulating the principle that revenue authorities must refrain from adjudicating disputes already pending before civil courts, the judgment addresses a persistent challenge in the Indian legal system and provides guidance for government authorities, litigants, and legal practitioners.

The court’s strong language and the imposition of exemplary costs signal a shift towards stricter enforcement of procedural discipline and greater intolerance for forum shopping and suppression of material facts. This approach is consistent with broader trends in Indian jurisprudence, where courts have increasingly been willing to use their powers to deter abuse of process and ensure that litigation is conducted in good faith. The judgment reinforces the principle that access to justice is not an absolute right but must be exercised responsibly and in accordance with established legal procedures.

Looking ahead, this judgment is likely to influence how similar cases are decided by courts across India. The clear articulation of the principle against parallel proceedings and the emphasis on civil court supremacy provide a strong precedent that can be cited in future cases involving jurisdictional conflicts between civil courts and administrative authorities. The judgment may also prompt legislative and policy reforms aimed at improving coordination between different forums and preventing parallel proceedings through better information sharing and case management systems.

One potential area for future development is the establishment of institutional mechanisms to facilitate coordination between civil courts and revenue authorities. This could include integrated case management systems that allow different forums to access information about pending cases, mandatory disclosure requirements for parties approaching revenue authorities, and protocols for communication between civil courts and administrative authorities when jurisdictional issues arise. Such mechanisms would help operationalize the principles articulated in this judgment and make it easier for government authorities to comply with their obligation to defer to civil court jurisdiction.

Another area for future development is the role of legal technology in preventing parallel proceedings and improving access to justice. As legal technology platforms become more sophisticated and widely adopted, they have the potential to address many of the challenges identified in this case. Comprehensive case search and tracking capabilities can help parties and their lawyers identify pending proceedings before approaching different forums. Automated alerts and notifications can keep parties informed about developments in related cases. Integrated case management systems can facilitate coordination between different forums and reduce the risk of conflicting decisions.

The judgment also raises important questions about the balance between jurisdictional propriety and access to justice. While the principle against parallel proceedings is important for maintaining the integrity of the legal system, it should not be applied in a manner that denies parties effective remedies or forces them to navigate complex and expensive judicial processes for relatively straightforward disputes. Future developments in this area may need to consider how to preserve the accessibility and informality of administrative proceedings while ensuring that jurisdictional boundaries are respected and that parties do not engage in forum shopping.

From a broader perspective, this judgment reflects the ongoing evolution of administrative law in India and the judiciary’s efforts to define the relationship between civil courts and administrative tribunals. The principle of civil court supremacy articulated in this judgment is consistent with the constitutional framework and the plenary jurisdiction of civil courts, but it also raises questions about the role and autonomy of specialized tribunals and administrative authorities. As India’s legal system continues to develop and as new specialized tribunals are created to address specific areas of law, courts will need to continue refining the principles governing jurisdictional boundaries and the relationship between different forums.

The judgment also has implications for the government’s efforts to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of dispute resolution mechanisms. While revenue authorities play an important role in providing accessible and expeditious resolution of certain types of disputes, this judgment makes clear that they must operate within their jurisdictional limits and defer to civil courts when appropriate. This may require investment in training for revenue officials, development of standard operating procedures for handling jurisdictional issues, and creation of institutional mechanisms for coordination with civil courts.

In conclusion, the Farooq Ahmad Shiekh judgment is a landmark decision that addresses fundamental issues of jurisdictional propriety, procedural discipline, and ethical conduct in litigation. The judgment provides clear guidance for government authorities facing the challenge of maintaining jurisdictional boundaries while fulfilling their administrative responsibilities. It sends a strong message to litigants about the consequences of forum shopping and suppression of material facts. And it contributes to the ongoing development of administrative law principles that govern the relationship between civil courts and administrative authorities. As the Indian legal system continues to evolve, this judgment will serve as an important reference point for addressing the challenges of parallel proceedings and ensuring that justice is administered in an orderly, efficient, and fair manner.

How Claw Legaltech Can Help?

In the context of the challenges highlighted by the Farooq Ahmad Shiekh judgment—particularly the issues of parallel proceedings, suppression of material facts, and coordination between different forums—Claw Legaltech offers innovative solutions that can help lawyers, litigants, and government authorities navigate the complexities of the Indian legal system more effectively.

AI Case Search and Judgment Database are two of Claw Legaltech’s most powerful features that directly address the challenges identified in this judgment. The platform provides access to over 100 crore (1 billion) rulings from courts and tribunals across India, making it easy to search for relevant precedents and verify whether similar disputes are pending before other forums. For lawyers representing clients in property disputes or matters involving revenue authorities, the AI Case Search feature can quickly identify relevant judgments on jurisdictional issues, parallel proceedings, and the relationship between civil courts and administrative authorities. This comprehensive access to case law helps ensure that legal arguments are well-supported by precedent and that parties are aware of their obligations regarding disclosure of pending proceedings.

Legal GPT is another invaluable tool that can assist lawyers and litigants in understanding complex legal principles and drafting appropriate pleadings. In cases involving jurisdictional conflicts, Legal GPT can provide quick answers to queries about which forum has jurisdiction, what remedies are available, and what disclosure obligations parties have. The tool can also assist in drafting applications, affidavits, and other legal documents that comply with procedural requirements and ethical standards. By providing instant access to legal knowledge and drafting assistance, Legal GPT helps ensure that parties approach courts and tribunals with complete and accurate information, thereby avoiding the kind of suppression of material facts that led to costs being imposed in the Farooq Ahmad Shiekh case.

Case Alerts and WhatsApp/Email Alerts features help lawyers and litigants stay informed about developments in their cases and related proceedings. These automated notification systems can alert parties when new orders are passed, hearing dates are scheduled, or judgments are delivered. For government authorities dealing with multiple proceedings across different forums, these alert systems can help ensure that they are aware of all relevant developments and can coordinate their actions accordingly. The alerts can also help prevent situations where parties inadvertently pursue parallel proceedings without being aware of related cases in other forums.

By leveraging these advanced legal technology tools, lawyers, litigants, and government authorities can better navigate the challenges of jurisdictional boundaries, prevent parallel proceedings, and ensure compliance with procedural and ethical obligations. Claw Legaltech empowers users with the information, tools, and insights needed to practice law more effectively and to contribute to the orderly administration of justice in India.