Objective

To delineate the medico-legal distinction between deficiency in service and medical negligence in the context of hospitalized patient care under the Consumer Protection Act (CPA) in India, and to clarify the appropriate attribution of liability between hospitals and physicians.

Methods

A doctrinal legal analysis was undertaken, examining statutory provisions (Consumer Protection Act, Clinical Establishments Act, Indian Penal Code, Indian Contract Act, and constitutional mandates) alongside leading case law (Indian Medical Association v. V.P. Shantha, Lakshmi Rajan v. Malar Hospital, and recent Supreme Court clarifications).

The study systematically compared:

- Institutional lapses (infrastructure, SOP compliance, administrative duties)

- Clinical failures (non-treatment, denial of treatment, improper treatment)

Results

The analysis demonstrates that:

- Deficiency in service arises from systemic or administrative shortcomings attributable to hospitals, such as failure to provide mandatory facilities or comply with statutory SOPs.

- Medical negligence is confined to clinical misjudgment or improper medical acts by physicians, requiring proof of causation through denial, non-treatment, or improper treatment.

- Payment for medical services establishes a contractual relationship but does not automatically convert negligent acts into deficiency in service.

- Case law consistently reinforces hospital liability for systemic failures while limiting physician liability to demonstrable clinical negligence.

Comparative Liability Framework

| Aspect | Deficiency in Service | Medical Negligence |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Failure | Systemic or administrative lapse | Clinical misjudgment or improper act |

| Primary Liable Party | Hospital or institution | Physician |

| Proof Required | Failure in service delivery or SOP compliance | Causation through denial, non-treatment, or improper treatment |

| Legal Basis | Consumer Protection Act | Tort and professional negligence principles |

Conclusion

Deficiency in service and medical negligence are distinct legal constructs requiring separate attribution of liability. Hospitals are accountable for systemic and infrastructural lapses, while physicians are liable only for clinical misjudgment or incompetence.

The CPA provides a forum for consumer redress in cases of deficiency linked to service delivery, whereas homicide and related offences remain within the domain of criminal law. This distinction ensures fair adjudication, balanced accountability, and protection of both patient rights and practitioner responsibilities.

Question: Filing a Civil Complaint Under the Consumer Protection Act (CPA)

Q. Can one file a civil complaint for monetary compensation under CPA for an offence of –

- Culpable homicide not amounting to murder?

- Non-culpable homicide?

- Attempt to cause homicide by inflicting grievous life-threatening injury?

Overview: Interface Between Criminal Law and Consumer Protection Law

This is a very sharp and important question. Let’s break it down carefully, because it touches the interface between criminal law and consumer protection law (CPA) in India.

Key Principles

- The Consumer Protection Act (CPA) is designed to address deficiency of service or defective goods in a consumer–service provider relationship.

- Criminal offences like homicide or attempt to homicide fall under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and are prosecuted by the State.

- Civil compensation for such offences is usually sought under tort law (wrongful death, negligence, medical malpractice) or through civil suits for damages, not under CPA.

- CPA jurisdiction applies only when there is a consumer–service provider nexus (e.g., hospital–patient, doctor–patient, product–consumer).

Your Specific Scenarios

1. Culpable Homicide Not Amounting to Murder (IPC §299 / §304)

- This is a criminal offence.

- Victim’s family can seek compensation through:

- Criminal court (via compensation under CrPC §357).

- Civil suit for damages (tort claim).

CPA Applicability: Only if the homicide resulted from deficiency in service (e.g., gross medical negligence in a hospital). Then, a complaint for compensation may be filed under CPA.

Otherwise, CPA is not the right forum.

2. Non-Culpable Homicide (Accidental Death Without Criminal Liability)

- If it is truly non-culpable (no negligence, no wrongful act), then no liability arises under IPC or tort law.

CPA Applicability: Only if the death was linked to defective goods or services (e.g., faulty medical equipment, unsafe product). In such cases, CPA can be invoked for compensation.

If it was a pure accident without a consumer–service nexus, CPA does not apply.

3. Attempt to Cause Homicide by Inflicting Grievous Life-Threatening Injury (IPC §307)

- This is a serious criminal offence.

- Compensation can be ordered by criminal courts under CrPC §357.

CPA Applicability: Again, only if the injury arose due to deficiency in service or defective goods.

Examples:

- Hospital negligence causing life-threatening injury.

- Defective drug or medical device causing grievous harm.

In such cases, CPA can be used to claim damages. Otherwise, CPA is not the forum.

Conclusion

- CPA is not a substitute for criminal prosecution.

- It can only be used for monetary compensation where the offence is linked to a consumer–service provider or consumer–product relationship.

- For homicide or attempt to homicide, the primary remedy is criminal law.

- Civil damages can be pursued separately under tort law or through compensation orders in criminal proceedings.

- CPA jurisdiction is limited to consumer disputes involving deficiency or defect.

In Short

| Nature of Case | Proper Forum |

|---|---|

| Direct homicide offences | Criminal courts |

| Compensation for negligence or deficiency | CPA (only if consumer nexus exists) |

Q. In treatment of a hospitalized patient deficiency in service is shortcoming in providing mandatory infrastructural facilities, failure to follow mandatory SOPs for the functioning of the hospital and lack of administrative and supervisory duties of the hospital head. If this causes death of a patient it can be equated with medical negligence for which hospital is liable and not the treating physician.

For a medical treatment, it has to be either non treatment, denial of treatment or improper treatment, for it to cause death. Inadequacy in treatment does not cause death. Simply because the patient paid for the treatment a negligent medical act does not become a deficiency .

AI : >

You’re articulating a very important medico‑legal distinction here. Let me help you refine and structure it so it reads as a clear, authoritative argument:

Deficiency in Service vs. Medical Negligence

1. Deficiency in Service (Hospital Liability)

Definition: Shortcomings in providing mandatory infrastructural facilities, failure to follow mandatory SOPs, and lack of administrative or supervisory duties by hospital management.

Implication: If such systemic failures cause the death of a patient, they can be equated with medical negligence attributable to the hospital as an institution.

Responsibility: The liability rests with the hospital administration, not the treating physician, because the lapse is organizational rather than clinical.

2. Medical Treatment (Physician Liability)

Criteria for negligence in treatment:

- Non-treatment: Failure to provide any medical intervention when required.

- Denial of treatment: Refusal to treat despite obligation and capacity.

- Improper treatment: Active medical intervention that is incorrect, unsafe, or below accepted standards.

Clarification:

- Inadequacy in treatment (e.g., limited resources or partial measures) does not automatically equate to negligence or cause of death.

- A negligent medical act does not transform into “deficiency in service” merely because the patient paid for treatment. Payment establishes a contractual relationship, but liability depends on the nature of the lapse.

3. Key Distinction

| Aspect | Hospital | Physician |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Lapse | Systemic / Administrative Failure | Clinical Misjudgment or Improper Medical Act |

| Cause of Death | Infrastructural or SOP Failure | Denial, Non-Treatment, or Improper Treatment |

4. Legal Positioning

This framework helps courts and tribunals separate:

- Institutional liability (hospital as service provider under consumer protection law).

- Individual liability (doctor under medical negligence jurisprudence).

It avoids conflating deficiency in service with clinical negligence, ensuring fair attribution of responsibility.

Medico-Legal Note on Deficiency in Service vs. Medical Negligence

Issue: Attribution of liability in the event of a patient’s death arising from hospital shortcomings versus physician conduct.

1. Deficiency in Service (Hospital Liability)

- Definition: Deficiency in service encompasses failure to provide mandatory infrastructural facilities, non-compliance with statutory SOPs governing hospital functioning, and lapses in administrative or supervisory duties by the hospital head.

- Legal Position: Where such systemic failures directly result in the death of a patient, they constitute negligence attributable to the hospital as an institution.

- Responsibility: Liability rests with the hospital administration, not the treating physician, since the lapse is organizational rather than clinical.

2. Medical Negligence (Physician Liability)

Criteria: For medical treatment to amount to negligence causing death, it must fall into one of the following categories:

- Non-treatment: Failure to provide medical intervention when required.

- Denial of treatment: Refusal to treat despite obligation and capacity.

- Improper treatment: Active medical intervention that is incorrect, unsafe, or below accepted standards.

Clarification: Inadequacy in treatment, by itself, does not equate to negligence or causation of death. Payment for treatment does not convert a negligent act into “deficiency in service”; liability depends on the nature of the lapse, not the financial transaction.

3. Distinction in Liability

- Hospital negligence: Systemic or administrative failure.

- Physician negligence: Clinical misjudgment or improper medical act.

- Causation of death: Must be directly linked either to denial, non-treatment, or improper treatment (physician) or infrastructural or SOP failure (hospital).

4. Submission

It is respectfully submitted that:

- Deficiency in service is distinct from medical negligence.

- Death caused by infrastructural or administrative lapses is attributable to the hospital.

- Death caused by non-treatment, denial, or improper treatment is attributable to the physician.

- Inadequacy in treatment or mere payment for services does not, in law, constitute deficiency or negligence.

Therefore, liability must be apportioned correctly: systemic failures to the hospital and clinical failures to the physician, ensuring fair and just adjudication.

Authorities

- Indian Medical Association v. V.P. Shantha & Ors. (1995 AIR 550; 1995 SCC (6) 651)

Principle: Medical services fall within the ambit of “service” under the Consumer Protection Act. Patients may hold hospitals accountable for deficiency in service. - Lakshmi Rajan v. Malar Hospital (Supreme Court of India)

Principle: Hospitals are liable for systemic failures and negligence in providing adequate facilities and care, reinforcing the distinction between institutional and physician liability. - Kamineni Hospitals Case (Supreme Court, 2025)

Principle: Hospital held vicariously liable for negligence of its staff doctor, establishing that institutional responsibility extends to supervisory and infrastructural duties. - Supreme Court Clarification on Doctor Liability (2025)

Principle: A doctor is liable only if proven to lack necessary qualifications or fail to exercise reasonable expertise, clarifying the threshold for clinical negligence.

Usage in Argument

- IMA v. Shantha anchors the statutory inclusion of medical services under consumer law.

- Lakshmi Rajan and Kamineni Hospitals demonstrate hospital liability for systemic lapses.

- Supreme Court clarification (2025) delineates physician liability strictly to clinical misjudgment or incompetence.

Together, these authorities support the proposition that deficiency in service is distinct from medical negligence, and liability must be apportioned accordingly.

Q. Format this into a “Table of Authorities” style (case name, citation, principle)

Table Of Authorities

| Case Name | Citation | Principle Established |

|---|---|---|

| Indian Medical Association v. V.P. Shantha & Ors. | 1995 AIR 550; 1995 SCC (6) 651 | Medical services fall within “service” under the Consumer Protection Act; hospitals accountable for deficiency in service. |

| Lakshmi Rajan v. Malar Hospital Ltd. | Supreme Court Of India | Hospitals liable for systemic failures and negligence in providing adequate facilities; distinction between institutional and physician liability. |

| Kamineni Hospitals Case | Supreme Court Of India, 2025 | Hospital held vicariously liable for negligence of staff doctor; institutional responsibility extends to supervisory and infrastructural duties. |

| Supreme Court Clarification On Doctor Liability | Supreme Court Of India, 2025 | Physician liability arises only if lacking qualifications or failing to exercise reasonable expertise; sets threshold for clinical negligence. |

Notes For Submission

- IMA v. Shantha anchors statutory inclusion of medical services under consumer law.

- Lakshmi Rajan and Kamineni Hospitals demonstrate hospital liability for systemic lapses.

- SC Clarification (2025) delineates physician liability strictly to clinical misjudgment or incompetence.

Together, these authorities reinforce the argument that deficiency in service is distinct from medical negligence, ensuring liability is apportioned fairly between hospital and physician.

List Of Statutory Provisions

| Statute / Provision | Citation | Relevance / Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Protection Act, 1986 (Now Replaced By The Consumer Protection Act, 2019) | Sections 2(1)(o), 2(1)(g), 2(1)(r) | Defines “service” to include medical services; “deficiency” as any shortcoming in service; empowers patients to seek redress for hospital lapses. |

| Clinical Establishments (Registration And Regulation) Act, 2010 | Sections 2(c), 11, 12 | Mandates registration and adherence to prescribed standards for hospitals; failure to comply amounts to deficiency in service. |

| Indian Penal Code, 1860 | Sections 304A, 336, 337, 338 | Provides criminal liability framework for rash or negligent acts causing death or injury; distinguishes individual negligence from systemic lapses. |

| Indian Contract Act, 1872 | Sections 73, 74 | Establishes liability for breach of contractual obligations; payment for medical services creates contractual duty but does not convert negligence into deficiency. |

| Constitution Of India | Article 21 (Right To Life), Article 47 (Duty Of State To Improve Public Health) | Reinforces the obligation of hospitals to maintain infrastructure and SOPs as part of protecting life and health. |

Notes For Submission

- Consumer Protection Act anchors hospital liability for deficiency in service.

- Clinical Establishments Act sets mandatory standards; non-compliance = systemic negligence.

- IPC provisions clarify criminal negligence distinct from civil deficiency.

- Contract Act prevents conflation of payment with liability.

- Constitutional provisions elevate hospital duties to fundamental rights and directive principles.

Post Script

Q. Vicarious Liability

A hospital is vicariously liable for all acts of medical negligence of the physicians engaged by it for providing treatment, but vice versa is not true: independent medical consultants on-fee-for service contract are not liable for the deficiency / negligence of hospital for the services the hospital provided against payment. Please critique and elaborate.

AI: Quick Answer

You are correct that hospitals in India are generally held vicariously liable for the negligence of doctors they engage, but independent consultants are not liable for hospital-level deficiencies. However, this principle is nuanced: liability depends on the nature of the doctor’s engagement, the hospital’s representations to patients, and the scope of the duty of care. Courts increasingly emphasize the hospital’s non-delegable duty to ensure safe treatment, while consultants remain liable only for their own professional acts.

Key Principles of Vicarious Liability in Healthcare

Hospital’s Liability

- Hospitals owe a non-delegable duty of care to patients. This means they cannot escape responsibility by claiming that negligence was committed by an independent doctor.

- Courts have held hospitals liable for negligence of doctors, nurses, and staff they provide to patients, regardless of contractual arrangements.

- Example: Kamineni Hospitals v. A. Pratibha (2023) reaffirmed that hospitals are accountable for systemic failures and negligence of engaged physicians.

Independent Consultant’s Liability

- Consultants on a fee-for-service basis are liable only for their own acts of negligence in diagnosis or treatment.

- They are not vicariously liable for hospital deficiencies such as poor infrastructure, faulty equipment, or administrative lapses.

- Courts distinguish between negligence in clinical judgment (doctor’s liability) and negligence in service delivery (hospital’s liability).

Comparison Table

| Aspect | Hospital | Independent Consultant |

|---|---|---|

| Duty of Care | Non-delegable, covers all services provided | Limited to professional skill and judgment |

| Liability for Staff Errors | Yes, hospital is liable for nurses, technicians, resident doctors | No, unless consultant directly supervises and fails |

| Liability for Infrastructure Failures | Yes (equipment malfunction, hygiene, administration) | No |

| Liability for Own Negligence | Yes, if hospital-employed doctor errs | Yes, if consultant errs in diagnosis/treatment |

| Vicarious Liability | Broad, extends to all engaged personnel | Narrow, does not extend to hospital deficiencies |

Critique of the Statement

- Accurate but Simplified: The statement rightly captures the asymmetry: hospitals are liable for doctors, but doctors are not liable for hospitals. However, it oversimplifies by ignoring shared liability scenarios. For example, if a consultant knowingly uses defective hospital equipment, liability may be apportioned.

- Evolving Jurisprudence: Indian courts are moving toward a patient-centric approach, emphasizing transparency and informed consent. Hospitals cannot hide behind contracts with consultants, but consultants also cannot escape liability for their own negligence.

Policy Rationale

- Hospitals are seen as service providers under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, and thus bear responsibility for the entire treatment package.

- Consultants are seen as professionals offering specialized skill, not as providers of infrastructure or systemic services.

Risks & Challenges

- Blurred Lines: In practice, patients rarely distinguish between hospital-employed doctors and independent consultants. Courts often interpret liability in favor of patients.

- CSR & Ethical Duty: Hospitals must ensure robust systems to prevent negligence, while consultants must insist on safe conditions before treating.

- Audit & Compliance: Hospitals should maintain medico-legal audit frameworks to protect both institutions and practitioners.

Bottom Line

Hospitals carry a wider umbrella of liability due to their non-delegable duty of care, while independent consultants are liable only for their own professional negligence. The asymmetry protects patients but requires hospitals to strengthen compliance and consultants to safeguard their practice boundaries.

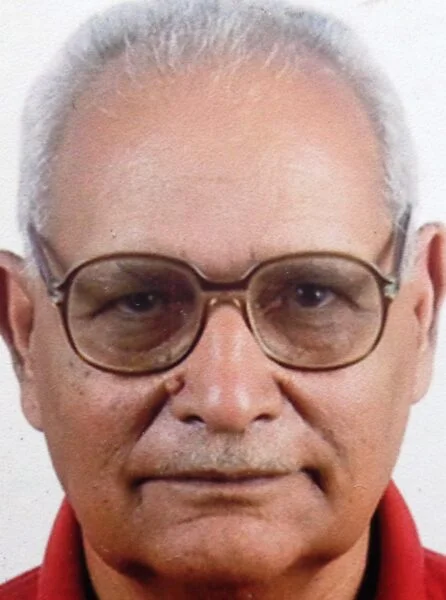

Written By: Dr Shri Gopal Kabra, MBBS, LLB, MSc, MS (Anatomy), MS (Surgery)

Bhagwan Mahaveer Cancer Hospital, Jaipur-302017

Email: [email protected], Ph no: 8003516198