Headquarters Do Not Confer Nationwide Jurisdiction

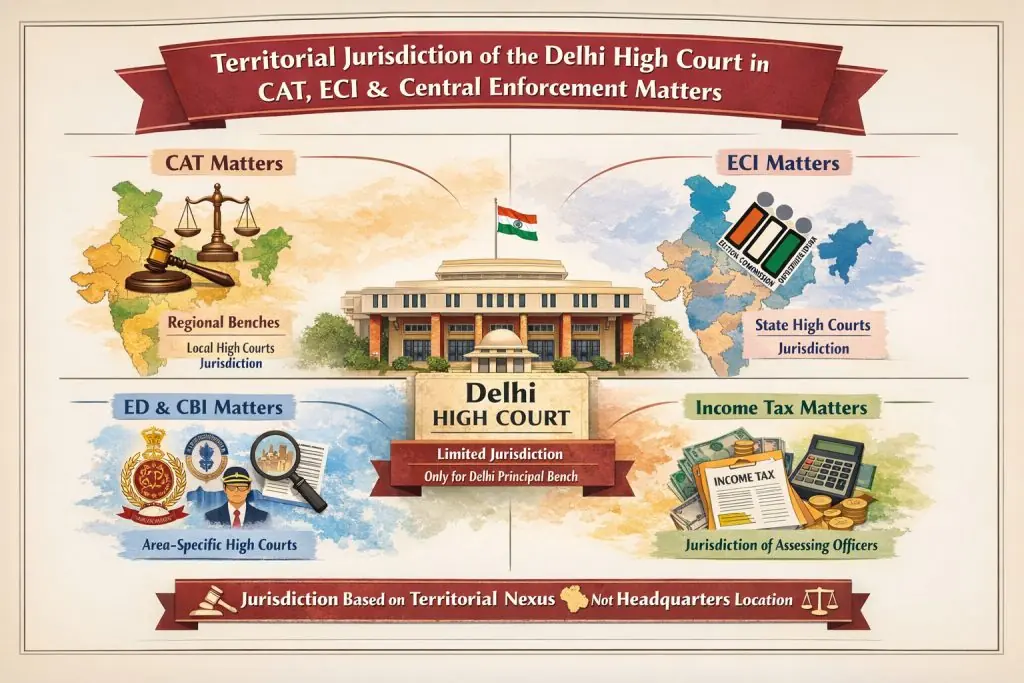

A recurring misconception in constitutional and administrative litigation is that the Delhi High Court (DHC) enjoys overarching or supervisory jurisdiction over central authorities and tribunals—such as the Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT), the Election Commission of India (ECI), the Enforcement Directorate (ED), the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), or Income Tax authorities—merely because their headquarters or Principal Bench is located in New Delhi. Indian constitutional jurisprudence has consistently rejected this assumption.

Jurisdiction under Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution is not determined by the situs of an authority’s headquarters alone, but by territorial nexus—that is, the place where the cause of action arises, the impugned order is passed or implemented, or the tribunal/authority exercising power is territorially situated.

Through a long line of authoritative judgments, the Supreme Court has clarified that the Delhi High Court does not possess blanket, nationwide, or supervisory jurisdiction over CAT, ECI, or other central enforcement bodies solely due to their presence in Delhi. This article examines the settled legal position with reference to CAT, ECI, ED, CBI, and Income Tax matters, supported by leading case law.

- Jurisdiction in Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) Matters

Constitutional Position after L. Chandra Kumar

The constitutional framework governing tribunal review was conclusively settled in L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997). The Supreme Court held that:

- Tribunals such as CAT function as courts of first instance in service matters;

- Their decisions are subject to judicial review under Articles 226 and 227;

- Such review must be exercised by the High Court within whose territorial jurisdiction the concerned tribunal bench is situated.

This ruling rejected the concept of centralized High Court supervision over tribunals and restored the federal balance inherent in the constitutional scheme.

- No Nationwide Jurisdiction for the Delhi High Court

The mere fact that:

- CAT’s Principal Bench, or

- The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT)

is located in Delhi does not confer jurisdiction on the Delhi High Court over CAT orders passed elsewhere.

This principle was emphatically reaffirmed in Union of India v. Alapan Bandyopadhyay (2022), where the Supreme Court clarified that:

- Orders passed by the CAT Principal Bench, New Delhi fall within the jurisdiction of the Delhi High Court;

- Orders passed by regional CAT benches must be challenged before the respective High Court having territorial jurisdiction over that bench;

- Even administrative or transfer orders under Section 25 of the Administrative Tribunals Act, 1985, when issued by the Principal Bench, are reviewable only by the Delhi High Court, but not vice versa.

Thus, the Delhi High Court’s jurisdiction in CAT matters is exclusive but limited, confined strictly to orders of the Principal Bench or causes of action arising within Delhi.

- Rationale: Preventing Forum Shopping

This territorial limitation serves vital constitutional objectives:

- Prevents forum shopping

- Ensures access to justice at the local level

- Respects the federal judicial structure

- Avoids over-centralization of constitutional remedies

Accordingly, a CAT litigant posted in Maharashtra or Tamil Nadu cannot bypass the Bombay or Madras High Court merely because CAT’s headquarters are in Delhi.

- Jurisdiction in Election Commission of India (ECI) Matters

Early Constitutional Position: Saka Venkata Rao

The territorial scope of writ jurisdiction in relation to the Election Commission of India (ECI) was first defined in Election Commission of India v. Saka Venkata Rao (1953). The Supreme Court ruled that a High Court cannot exercise its writ power under Article 226 against an authority located outside its geographical jurisdiction, even if the consequences of that authority’s actions are felt within the state. The mere fact that a decision impacts rights or interests within a state does not empower the local High Court to take jurisdiction over an out-of-state body.

Applying this principle, the Court held that the Madras High Court had no authority to issue writs against the ECI, which was based in New Delhi, despite the electoral issues arising in Madras State. This decision laid down the essential principle that the physical location of the authority is decisive in determining writ jurisdiction, unless an exception is provided under the Constitution.

- Expansion under Article 226(2): Cause of Action Test

Post the 15th Constitutional Amendment, Article 226(2) broadened judicial oversight by empowering High Courts to adjudicate writ petitions when any part or entirety of the actionable cause occurs within their territorial jurisdiction. However, a critical caveat persists: the Delhi High Court cannot claim automatic authority over matters involving the Electoral Commission of India (ECI) solely on account of the Commission’s headquarters at Nirvachan Sadan, New Delhi. Jurisdiction remains contingent on specific contextual factors tied to the dispute rather than location of institutional offices.

The determination of judicial authority hinges on three pivotal elements: the locale where the contested decision was formulated, the site of its enforcement, or the origin of the electoral proceedings or voting-related grievances. This framework ensures that jurisdiction is anchored in the factual nexus of the case rather than administrative convenience, preserving the integrity of territorial judicial boundaries.

- Application to ECI Disputes

Accordingly:

- Election petitions under the Representation of the People Act, 1951 lie exclusively before the High Court of the concerned State;

- Writ petitions challenging ECI actions must ordinarily be filed before the High Court having a substantial territorial connection to the dispute.

While the Delhi High Court has occasionally entertained national-level policy matters, political party recognition disputes, or issues intrinsically linked to decisions taken at ECI headquarters, such instances remain exceptions. The governing rule continues to be territorial nexus, not headquarters location.

- Jurisdiction in ED, CBI and Income Tax Matters

Enforcement Directorate (ED)

In matters arising under statutes such as the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA) or FEMA, the Supreme Court has consistently held that:

- Jurisdiction under Article 226 depends on where the cause of action arises, including:

- Place of search, seizure, arrest, summons, or attachment, or

- Location where the adjudicatory or coercive action is implemented.

The presence of the ED’s headquarters in Delhi does not confer jurisdiction on the Delhi High Court over actions carried out in other States. Courts have repeatedly cautioned against filing writ petitions in Delhi merely because policy decisions or supervisory control emanate from Delhi.

Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI)

Similarly, in CBI matters:

- Jurisdiction lies with the High Court within whose territorial limits:

- The FIR is registered,

- The investigation is conducted, or

- The impugned coercive action occurs.

The Supreme Court has deprecated the practice of invoking Delhi High Court jurisdiction merely because the CBI headquarters or Director’s office is located in Delhi. Such an approach would undermine federal judicial discipline and encourage forum shopping.

Income Tax Authorities

In Income Tax matters, jurisdiction is determined by:

- The Assessing Officer’s jurisdiction,

- The place where the assessment, reassessment, search, seizure, or recovery proceedings are undertaken, or

- Where the cause of action substantially arises.

The location of the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) or Ministry of Finance in Delhi does not vest nationwide writ jurisdiction in the Delhi High Court. Challenges must ordinarily be brought before the jurisdictional High Court corresponding to the territorial authority exercising statutory power.

- The Governing Principle: Territorial Nexus over Headquarters

Across CAT, ECI, ED, CBI, Income Tax, and similar central-authority matters, Supreme Court jurisprudence consistently prioritizes:

- Where the cause of action arises,

- Which authority or tribunal bench passed the order,

- Which territory bears a real and substantial connection to the dispute.

This approach:

- Upholds constitutional federalism,

- Distributes judicial workload equitably among High Courts,

- Prevents Delhi from becoming a default forum of convenience for nationwide litigation.

Conclusion

The Delhi High Court does not enjoy blanket or supervisory jurisdiction over the Central Administrative Tribunal, the Election Commission of India, the Enforcement Directorate, the Central Bureau of Investigation, Income Tax authorities, or other central bodies merely because their headquarters or Principal Bench is located in New Delhi. As settled in L. Chandra Kumar, Alapan Bandyopadhyay, and Saka Venkata Rao, judicial review under Articles 226 and 227 is territorially conditioned.

In CAT matters, jurisdiction lies with the High Court corresponding to the tribunal bench that passed the order. In ECI, ED, CBI, and Income Tax matters, jurisdiction depends on where the cause of action substantially arises, not on the situs of headquarters alone. This doctrine ensures constitutional discipline, prevents forum shopping, and preserves the federal structure of India’s judicial system.