Abstract

In this fast-paced and competitive business environment, companies always aim to increase strategic flexibility, enhance shareholder value, and improve efficiency. While merger and acquisition have been the go-to strategy for achieving this, later it has been recognized that bigger is not always better. There are a wide range of unrelated business units under one roof, which leads to lack of strategic focus, complex corporate governance, inefficient capital allocation, reduced transparency, etc.

Therefore, companies think that smaller and sharper might be smarter. Unlike merger, which involves uniting two or more companies to form a single entity, demerger involves the separation of a single entity into two or more independent entities. By undertaking demerger, a “conglomerate discount” can be eliminated, which can increase the total value of shareholders’ investment.

As a result of demerger, each company will focus on their core activities and report financial results separately. This transparency helps shareholders better understand the financial health and allows investors to make more informed decisions about where to invest or divest.

This paper presents a brief analysis of the concept of demerger and its growing importance in corporate restructuring. This can be further categorized into inbound and outbound cross-border demergers. We will also look into the types and impact of demerger. Through this paper, we will understand how demergers, both domestic and international, serve as strategic tools in modern corporate restructuring.

Introduction

Traditional corporate restructuring strategies such as merger and acquisitions aim to achieve economies of scale, diversification, and cost reduction. But they face problems like complex management, inability to focus on the core business, and less transparency.

- Complex management structures

- Lack of strategic focus

- Reduced transparency

- Inefficient capital utilization

By demerger, it allows each resulting entity to pursue its own strategic direction and create a sharper market identity. It also cuts unnecessary costs and attracts the right investors. Corporate restructuring not only involves domestic transactions but also across borders.

While cross-border merger is permitted in India and has legal provisions under the Companies Act, 2013, it does not explicitly permit cross-border demerger.

Case Example: Kwality Wall’s

In the case of Kwality Wall’s, it was originally started and marketed under Hindustan Unilever Limited. Later, it decided to spin-off its ice cream business into a new, separate company so that it could focus on its core business and KWIL’s performance and value would be more visible.

By separating, KWIL can manage costs better without being influenced by non-ice-cream business priorities.

Demerger

A demerger is a process by which a single company is divided into two or more separate and independent entities. In this process, part of the company’s assets, liabilities, and operations are transferred to the newly formed company. This helps the company to focus more on its specific business objectives.

Legal Framework under Companies Act, 2013

The legal provisions for demerger in the Companies Act, 2013 are outlined in Sections 230 to 233.

| Section | Provision | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Section 230 | Compromise or Arrangement | Provides the legal framework for companies to enter into schemes of arrangement, including demergers. |

| Section 231 | Power of Tribunal | Deals with the power of the tribunal to enforce compromise or arrangement. |

| Section 232 | Merger and Amalgamation | Mandates approval from NCLT, shareholders, and creditors before restructuring. |

| Section 233 | Fast Track Process | Allows certain companies to carry out mergers and demergers through a simplified process. |

Under Section 233, certain companies like wholly owned subsidiaries and small firms can carry out mergers and demergers through a faster process. The involved companies should file the required documents with the Registrar of Companies (ROC). If there are any suggestions or objections, they will be given by the Official Liquidator, and the Regional Director gives the final approval or raises objections within 60 days.

They do not need to seek approval from the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), which makes the demerger procedure faster and less complex for eligible companies.

Case Example: Reliance Industries Limited

Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) is one of India’s largest business groups, which executed a significant demerger in 2005, leading to the creation of four distinct entities:

- Reliance Communications Venture

- Reliance Energy Ventures

- Global Fuel Management Service

- Reliance Capital Venture

In 2023, Reliance Industries Limited undertook another important demerger by separating its financial services business into an independent company called Jio Financial Service Limited (JFSL).

Shareholders of RIL were granted one share in Jio Financial Service for every share they held in RIL, ensuring continued ownership in both companies.

Types of Demergers

Spin-Off

In a spin-off, a part of the parent company becomes a new, separate business entity while the parent company continues to operate. Shareholders of the parent company automatically receives shares from the new company based on what they already hold. This strategy this used to allow its new business grow on its own or unlock the value that is hidden in the large business.

Split-Off

A split-off is similar to a spin-off, but the key difference lies in how the shareholders are treated. In a split-off shareholders are given a choice, they must decide whether to remain invested in the parent company or invest in the new company. If they want shares in the new company then they can exchange some or all of their parent company shares for the shares in the new company. This method is often used to refine the shareholder base.

Split-Up

In a split-up, the parent company is completely divided into two or more independent companies which result in complete dissolution of the parent company. Shareholders automatically get shares in the new company based on their original holdings in the parent company.

Equity Carve-Out

An equity carve-out involves spinning off part of the parent company to create a new, legally separate entity. Then, a small portion of this new company is sold to the public through an initial public offering (IPO). The parent company still owns most of the new company and maintains control over it. However, the existing shareholders of the parent company do not automatically receive the shares in the new company, they can choose to buy them on the market if they want. This helps the parent company to raise capital while retaining control over the new entity.

Divestiture

A divestiture means that a company sells a part of its business to another company. Shareholders of the parent company do not receive any shares in the new company, they typically keep only their existing shares. This usually happens when the company wants to reduce debt or focus more on its core operations.

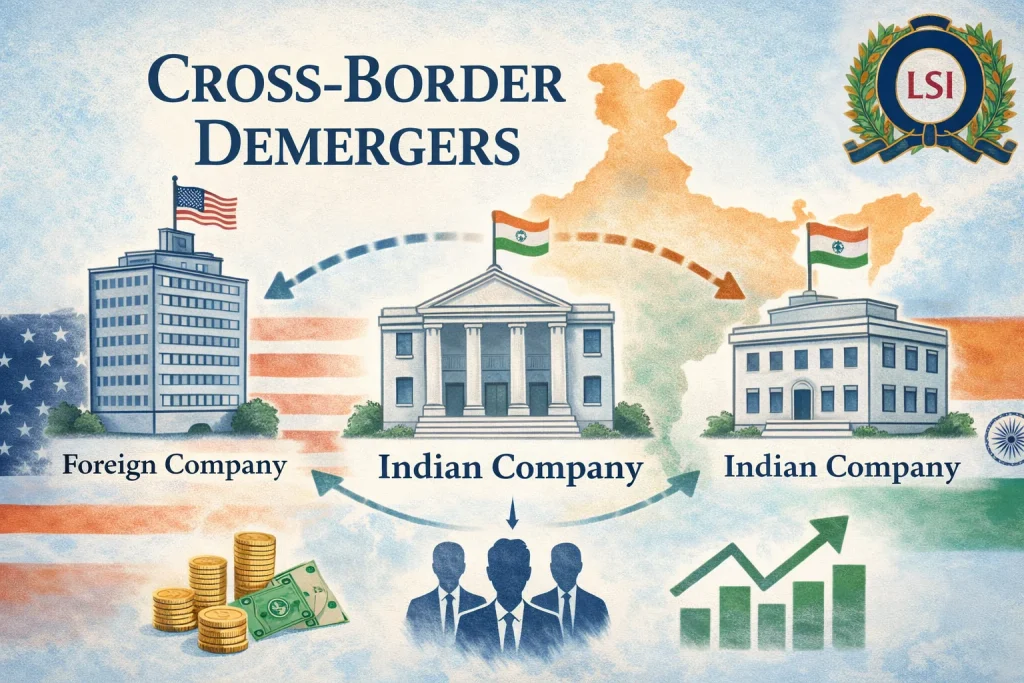

Cross-Border Demerger

A cross-border demerger is when a company splits off part of its business and moves it to another company based in a different country. It’s not just a paperwork shuffle. We’re talking about moving assets, liabilities, and entire business operations across borders, which means dealing with a whole new set of laws and regulations.

- These demergers are becoming more common in today’s global market.

- Companies aim to streamline operations and boost efficiency.

- The objective is to deliver better value to shareholders worldwide.

But compared to a regular, domestic demerger, the cross-border version gets messy fast. You’ve got to juggle legal, tax, and regulatory systems in more than one country. Companies need to get the green light from authorities in each place, understand how tax rules will hit them on both sides, and make sure the whole deal is legally valid everywhere it matters. The biggest headache? Making sure every country involved actually recognizes and approves the restructuring.

| Aspect | Domestic Demerger | Cross-Border Demerger |

|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | Single country | Multiple countries |

| Regulations | One legal system | Several legal systems |

| Tax Impact | Relatively simple | Complex and multi-layered |

| Approval Process | Local authorities | Authorities in all involved countries |

Inbound And Outbound Cross-Border Demergers

There are two main types of cross-border demergers, depending on where the business is headed:

Inbound Cross-Border Demerger

This happens when a foreign company moves part of its business to an Indian company. So the new, resulting company is set up (or already exists) in India, while the original company is based abroad. Picture a Singaporean company splitting off its Indian operations and handing them over to an Indian company — that’s inbound.

Outbound Cross-Border Demerger

Here, it’s the Indian company doing the splitting. It separates part of its business and transfers it to a company based in another country. For example, if an Indian company sends its overseas operations to a new company in the US, that’s outbound.

Key Differences

What really sets these two apart is where the new company ends up and which way the assets are moving. This matters, because it changes how approvals work, how taxes get handled, and what rights shareholders have.

| Aspect | Inbound Demerger | Outbound Demerger |

|---|---|---|

| Origin of Business | Foreign company | Indian company |

| Resulting Company | Indian company | Foreign company |

| Direction of Assets | Into India | Out of India |

| Regulatory Impact | Indian approvals required | Complex cross-border enforcement |

The Sun Pharma Cases: How Judges Set The Boundaries For Cross-Border Demergers In India

In the fast-evolving world of corporate restructuring, two pivotal cases involving Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Limited—one in 2018 and the other in 2019—marked a turning point for how Indian courts interpret and regulate cross-border demergers. Before these cases, legal clarity was lacking, leaving companies navigating a murky legal landscape businesses to rethink their global restructuring strategies.

The 2018 Sun Pharma Case: The Limits Of Outbound Demergers

The saga began in 2018, when Sun Pharma sought approval from the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) in Mumbai to implement a novel restructuring plan. The idea was to hive off its specialty business—primarily based outside India—and transfer it to Aditya Medi sales Limited, a group company incorporated in the United States.

Essentially, this was a classic outbound demerger: an Indian company carving out part of its business and relocating it to a foreign jurisdiction. When the NCLT examined this proposal, it took a firm stand against such outbound transactions. In its decision dated March 27, 2018, the tribunal cited several reasons rooted in statutory interpretation and practical enforcement issues:

Reasons For Rejection By The NCLT

- Jurisdictional Constraints: The NCLT emphasized that its authority was restricted to entities registered under Indian law. It had no power to pass binding orders on companies incorporated abroad, which would undermine the enforceability of any scheme involving a foreign transferee.

- Statutory Definitions: The Companies Act, 2013, clearly defines a “company” as an entity formed under Indian legislation. This means that foreign companies—like the US-based Aditya Medi sales—fall outside the purview of the Act and, by extension, the NCLT’s supervisory reach.

- Legislative Silence On Demergers: Parliament had specifically introduced Section 234 to provide for cross-border mergers, enabling Indian companies to merge with foreign entities in certain jurisdictions. However, there was no corresponding provision for demergers. The absence of a statutory framework for outbound demergers left the tribunal with no legal basis to approve such a transaction.

Impact Of The Verdict

This verdict sent a clear message: under current Indian company law, outbound cross-border demergers are not permissible. For Indian corporates with international ambitions, this created a significant roadblock.

Instead of demergers—which are typically tax-efficient and offer operational clarity—firms were forced to rely on alternatives like slump sales or share transfers. These workarounds are often less attractive, as they can involve higher tax liabilities, more regulatory scrutiny, and greater transactional complexity.

The 2019 Sun Pharma Case: Opening the Door to Inbound Demergers

The legal landscape shifted again just a year later. In 2019, Sun Pharma returned to the NCLT, but this time with a different restructuring proposal. The company wanted to transfer the Indian business of its Mauritius-based subsidiary, Aditya Acquisition Company Limited, into its Indian affiliate, Sun Pharma Laboratories Limited (later renamed Sun Pharma India).

Unlike the previous case, this was an inbound demerger: assets and business were moving from a foreign entity into an Indian one. On January 31, 2019, the NCLT gave its approval, marking a significant departure from its earlier restrictive approach.

Tribunal’s Reasoning and Key Principles

The tribunal’s reasoning illuminated the boundaries of permissible cross-border restructurings:

- Firm Jurisdiction: Because the resultant company was Indian, the NCLT could exercise full regulatory oversight and ensure compliance with its orders. The entire transaction would be subject to Indian law, making enforcement straightforward.

- Assets Anchored in India: All the business operations, assets, and liabilities involved were physically and legally situated in India, ensuring they remained within the Indian legal and regulatory net post-demerger.

- Dynamic Legal Interpretation: The NCLT adopted a purposive and pragmatic interpretation, recognizing that corporate restructuring should serve genuine business objectives and protect stakeholder interests, rather than be hamstrung by overly technical readings of the law.

- Shareholder Safeguards: The tribunal noted that shareholders of the foreign transferor would receive shares in the Indian transferee, thereby continuing to be protected by Indian regulations and oversight. This continuity of protection was a key factor in the NCLT’s approval.

Summary of Key Factors Considered by NCLT

| Factor | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Firm Jurisdiction | The resultant company was Indian, giving the NCLT full regulatory control. |

| Assets Anchored in India | All assets and liabilities remained within Indian legal jurisdiction. |

| Dynamic Legal Interpretation | The tribunal adopted a pragmatic and purposive reading of the law. |

| Shareholder Safeguards | Shareholders continued to enjoy protection under Indian regulations. |

The Legacy of the Sun Pharma Cases

Together, these two cases established a clear legal framework. Outbound cross-border demergers—where Indian businesses are split and transferred to foreign entities—remain prohibited under the current law, reflecting concerns over jurisdiction and enforceability. In contrast, inbound demergers—where foreign businesses are brought under the Indian company umbrella—are permissible, provided the resulting entity is Indian and remains subject to Indian law.

For Indian corporates, these decisions have had far-reaching consequences. The judgments clarified the scope of permissible restructuring, steering companies toward structures that keep assets and control within India if they want to benefit from demerger provisions. At the same time, the cases underscored the need for legislative reform if India is to fully embrace cross-border restructuring in a globalized economy. Until such reforms are made, Indian companies must navigate within the boundaries set by the Sun Pharma precedents, balancing legal certainty with business ambition.

Tax Neutrality in Cross-Border Demergers

Tax neutrality matters a lot in corporate restructurings, especially when companies split up across borders. When a deal is tax-neutral, neither the company nor its shareholders face immediate tax bills. This lets the restructuring happen smoothly, without a big tax hit.

Here’s where things stand under Indian tax law. The Income Tax Act, 1961, gives domestic demergers some breathing room. If a demerger meets the rules under Section 2(19AA) and a few other sections, it counts as tax-neutral. But once you cross borders, things get tricky.

Capital Gains Tax

First, capital gains tax. In an outbound demerger (if it were even allowed), when an Indian company moves assets to a foreign one, it usually counts as a taxable transfer. That means capital gains tax kicks in. The break for domestic demergers under Section 47(vib) doesn’t cover cross-border deals.

Tax on Shareholders

Then there’s tax on shareholders. For inbound deals, Indian shareholders who get shares in a new Indian company might dodge taxes under Section 47(vii)—but only if the demerger fits the legal definition. Foreign shareholders, on the other hand, have to deal with whatever their own countries’ tax laws and treaties say.

Withholding Tax and Transfer Pricing

Withholding tax is another headache. Cross-border deals can trigger withholding tax, depending on how the assets move and what the Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA) says. Plus, transfer pricing. Tax authorities keep a close eye on these deals. They want to make sure everything’s at arm’s length and that companies aren’t just shifting profits to dodge taxes.

Practical Implications

All this creates real uncertainty. There aren’t clear rules for tax-neutral cross-border demergers in India, so companies face the risk of extra taxes slipping through the cracks. Domestic deals get a straightforward framework, but cross-border ones need careful planning, sometimes even advance tax rulings, to avoid nasty surprises. And companies have to think about tax rules both in India and abroad, plus how tax treaties fit in.

| Aspect | Domestic Demergers | Cross-Border Demergers |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Status | Permissible under Indian law | Outbound prohibited, inbound limited |

| Tax Neutrality | Available under Section 2(19AA) | No clear tax-neutral framework |

| Capital Gains | Generally exempt | Usually taxable |

| Shareholder Tax | Exempt under Section 47(vii) | Depends on residence and treaties |

| Regulatory Complexity | Relatively simple | High, requires careful planning |

Protection of Small Shareholders

Keeping small and minority shareholders safe is a core part of any restructuring. The idea is simple: big players shouldn’t be able to steamroll everyone else.

What Safeguards Are in Place for Cross-Border Demergers?

Approval Process

Under Section 230 of the Companies Act, 2013, any arrangement—including demergers—needs approval from a majority in number and three-fourths in value of the shareholders who show up and vote. That means small shareholders get a real vote.

Role of the NCLT

Next, the NCLT (National Company Law Tribunal) steps in. The Tribunal checks whether the scheme is fair to everyone, not just the big guys. If something looks unfair to any group of stakeholders, they can throw out the deal.

Transparency Requirements

On top of that, companies have to lay everything out—valuation reports, fairness opinions, reasons for the deal. This transparency lets small shareholders actually understand what’s happening and decide for themselves.

Exit Options for Dissenting Shareholders

And if they don’t like it? Sometimes dissenting shareholders can cash out at a fair price, but it depends on the scheme and the law. Still, cross-border deals bring extra challenges for small shareholders.

Key Challenges Faced by Small Shareholders

- Information Asymmetry: Information isn’t always easy to come by. These deals can be complicated, stretching across countries, currencies, and different legal systems. Most small shareholders don’t have the resources to dig into all the details.

- Valuation Issues: Valuation is another problem. Figuring out what’s fair gets messy when you have different accounting standards, changing exchange rates, and market swings in other countries.

- Shareholder Rights: Then there’s the issue of rights. If small shareholders end up with shares in a foreign company, it’s tough to stay involved—attending meetings or seeking legal help in another country isn’t easy.

- Liquidity Constraints: Liquidity can be a real problem too. Shares in a foreign company might not trade easily on Indian exchanges, so small shareholders could get stuck holding stock they can’t sell.

Protection Mechanisms in Cross-Border Demergers

Because of all this, cross-border demerger schemes must build in solid protections—things like Indian Depository Receipts (IDRs) or making sure the new shares are listed in India, if possible. That way, small shareholders don’t get left out in the cold.

Conclusion

India’s domestic demerger framework under Sections 230-233 of the Companies Act, 2013, is well-established. However, cross-border demergers face significant challenges. The Sun Pharmaceutical cases (2018 and 2019) established that outbound cross-border demergers are not permissible while inbound cross-border demergers are permissible, creating asymmetry that limits Indian multinationals’ restructuring options.

Key Regulatory Challenges

| Challenge Area | Description |

|---|---|

| Tax Uncertainty | Ambiguity around capital gains and withholding taxes, creating uncertainty about tax neutrality. |

| Shareholder Protection | Inadequate safeguards for small shareholders facing information asymmetry and liquidity constraints. |

| Regulatory Approvals | Complex approvals requiring 12–24 months across multiple authorities. |

Need for Legislative Reform

Legislative reform is urgently needed. Amendments permitting outbound demergers, clearer tax provisions, and streamlined approvals would align India with international practices. Until comprehensive provisions address jurisdiction, taxation, and procedures, cross-border demergers’ full potential remains unrealized. A robust framework is essential for India’s global corporate competitiveness. Written By: Harshini.V.T