Introduction

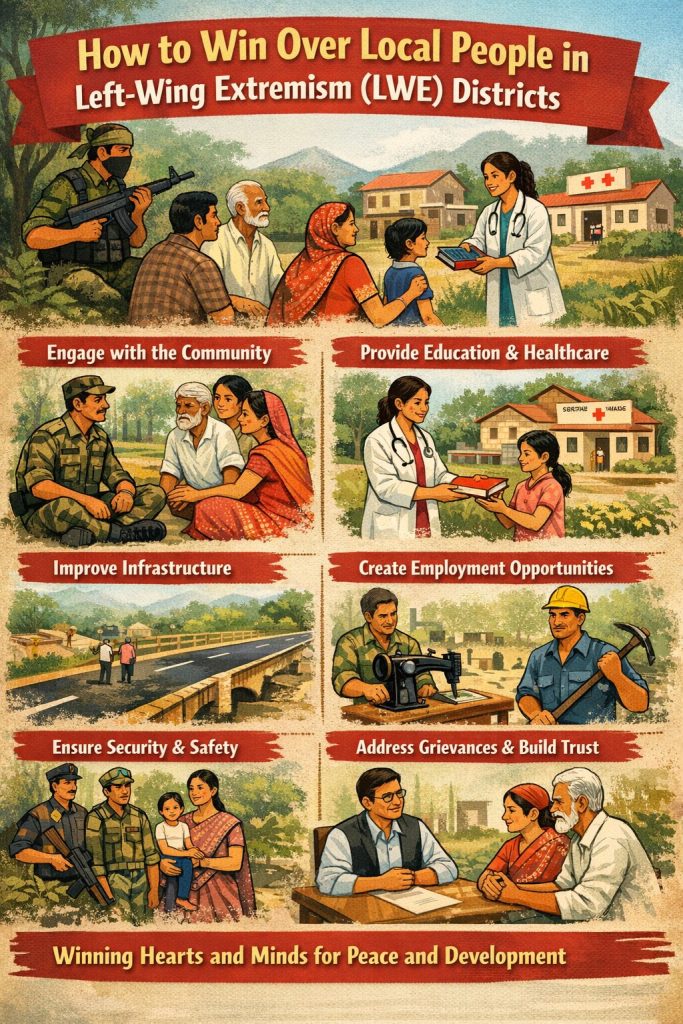

Left-Wing Extremism (LWE), long symbolized by the “Red Corridor,” remains one of India’s most enduring internal security challenges, rooted in decades of perceived neglect, exploitation, and alienation among tribal and rural communities in central and eastern India. While intensified security operations, infrastructure development, financial choking of extremists, and mass surrenders have dramatically reduced its footprint—from 126 affected districts in 2014 to just 11 (with only 3 classified as “most affected”) by late 2025, slashing violent incidents by over 80% from their 2010 peak—the deeper, more enduring challenge persists: winning the genuine trust of local populations who have historically viewed the state as an adversary rather than an ally.

Armed suppression may neutralize cadres and shrink territorial control in the short term, but lasting victory lies in fundamentally transforming the socio-political landscape—through equitable development, robust protection of rights (including forest and land entitlements), participatory governance, cultural respect, and economic dignity—so that affected communities embrace the democratic mainstream as partners in progress, ensuring no ideological space remains for resurgence beyond the government’s March 2026 eradication deadline.

Understanding the Roots of Alienation

To effectively counter Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) and prevent any resurgence in its remaining pockets—now confined to just eight districts (primarily in Chhattisgarh, with outliers in Jharkhand and Odisha) as of late 2025, with violence down over 80% from 2010 peaks—the state must first grasp why many tribal and rural communities in historically neglected forested regions have sympathized with, tolerated, or been coerced into supporting Maoist groups.

Deep-rooted historical neglect has left these areas outside mainstream development, manifesting in chronic poverty, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to education, healthcare, and livelihoods. Land alienation remains the single most significant driver: large-scale displacement from ancestral lands due to mining, dams, industrial projects, and resource extraction—often without fair compensation, rehabilitation, or meaningful consent—has bred profound resentment, exacerbated by the patchy implementation of protective laws like the Forest Rights Act (2006) and PESA (1996), which aimed to recognize community rights over Jal, Jungle, and Jameen but face administrative resistance and delays.

Weak governance compounds this through corruption, poor last-mile delivery of welfare schemes, bureaucratic apathy, and a persistent absence of basic services, creating a vacuum that extremists exploit to establish parallel authority. A pervasive cultural disconnect further alienates locals, as state institutions frequently disregard tribal traditions, languages, customary decision-making structures (e.g., gram sabhas), and indigenous knowledge systems, fostering a sense of erasure rather than inclusion.

Finally, communities often find themselves trapped in a cycle of fear between Maoist reprisals—such as branding and executing suspected informants—and heavy-handed or indiscriminate security operations, which can erode trust and push vulnerable populations toward neutrality or tacit support for extremists as a survival mechanism. Addressing these intertwined socio-economic, political, and cultural drivers of alienation is essential for transforming the state from perceived adversary to genuine ally, ensuring sustainable peace beyond the March 2026 eradication target.

Security with Sensitivity

In the endgame against Left-Wing Extremism—now confined to just eight districts with violence down ~88% from 2010 peaks—security operations must evolve from suppression to sensitivity, prioritizing minimum force and maximum trust to prevent alienation and secure lasting community support. Heavy-handed tactics, which historically eroded credibility and fueled resentment among tribal populations caught in crossfire, are being supplanted by calibrated, intelligence-led actions that emphasize civilian protection, strict rules of engagement, and avoidance of collateral damage, aligning with the national policy’s holistic approach of security alongside development and rights.

Community policing forms the cornerstone: actively recruiting and integrating local tribal youth into police and auxiliary forces—such as the District Reserve Guards (DRG) in Chhattisgarh’s Bastar region, where young men and women from remote interiors bring invaluable terrain knowledge, cultural familiarity, and legitimacy—builds bridges, reduces fear of “outsider” forces, and fosters a sense of ownership in security.

Recent successes, including tribal youths from Naxal-hit areas clearing SSC and state police exams after specialized coaching (e.g., by ITBP), demonstrate how such inclusion transforms potential recruits for extremists into stakeholders in mainstream governance. Transparency further counters Maoist propaganda: publicly communicating the purpose, duration, and humanitarian safeguards of operations—through village-level interactions, media briefings, and Civic Action Programmes (CAP) under the Modernization of Police Forces scheme—dispels misinformation, humanizes security personnel, and reassures communities that the state acts as protector rather than oppressor.

By embedding these principles—minimum force with accountability, localized policing, and open dialogue—security efforts not only neutralize remaining threats but also accelerate the irreversible shift toward trust, cooperation, and irreversible peace by the March 2026 deadline.

Case Example

In Chhattisgarh, the Bastariya Battalion of CRPF recruited local tribal youth. Their cultural familiarity and language skills improved trust and reduced hostility toward security forces.

Development as a Trust-Building Tool

Development is the most powerful weapon against extremism. When people see tangible improvements in their lives, extremist narratives lose credibility.

Infrastructure

- Roads and mobile connectivity reduce isolation.

- Electrification projects enable education and small businesses.

Education

- Residential schools like Eklavya Model Schools provide quality education to tribal children.

- Training local teachers ensures cultural sensitivity.

Healthcare

- Mobile health units reach remote villages.

- Recruiting local youth as health workers bridges trust gaps.

Case Example

Odisha’s mobile health units in Malkangiri district significantly improved maternal health outcomes, enhancing the state’s credibility among tribal communities.

Ensuring Rights and Entitlements

Winning trust requires ensuring that locals feel the state protects their rights.

- Land Rights: Effective implementation of the Forest Rights Act grants ownership to tribal communities.

- Welfare Schemes: Access to PDS, pensions, and MGNREGA wages must be guaranteed without corruption.

- Legal Aid: Free legal services protect locals from exploitation by contractors and middlemen.

Case Example

In Jharkhand, proactive distribution of land titles under the Forest Rights Act reduced grievances and weakened extremist recruitment.

Cultural and Social Integration

Respecting local identity is crucial.

- Festivals and Traditions: Celebrate tribal festivals at district level to show respect.

- Language Inclusion: Use local dialects in government communication.

- Community Leaders: Engage village elders and traditional institutions in decision-making.

Case Example

In Andhra Pradesh, integrating tribal dance and music into official events fostered cultural pride and reduced alienation.

Economic Empowerment

Economic opportunities reduce the appeal of extremist recruitment.

- Forest-Based Livelihoods: Promote lac, tendu leaves, bamboo, and honey collection.

- Cooperatives: Ensure fair pricing of local produce.

- Microfinance and SHGs: Support women-led enterprises.

Case Example

Self-Help Groups in Gadchiroli (Maharashtra) empowered women economically, making them less vulnerable to extremist influence.

Communication and Counter-Narratives

Extremists thrive on propaganda. The state must counter this effectively.

- Local Radio & Theatre: Share development stories in local languages.

- Youth Engagement: Organize sports tournaments, cultural programs, and scholarships.

- Grievance Redressal Camps: Regular camps show responsiveness and accountability.

Case Example

In Jharkhand, community radio stations broadcasting in tribal dialects helped counter extremist narratives and spread awareness about welfare schemes.

Role of Civil Society

Civil society organizations can act as neutral facilitators.

- NGOs provide vocational training and awareness campaigns.

- Faith-based groups offer humanitarian support.

- Academic institutions conduct research and monitoring.

Case Example

In Odisha, NGOs partnered with the government to run skill development centers, reducing youth vulnerability to extremist recruitment.

Case Studies of Success

- Jharkhand: Skill development centers reduced youth recruitment.

- Odisha: Mobile health units improved state image.

- Chhattisgarh: Community policing initiatives increased trust.

- Andhra Pradesh: Cultural integration fostered belonging.

Challenges Ahead

Despite remarkable progress—reducing LWE-affected districts to just eight (six in Chhattisgarh, including Bijapur, Sukma, Narayanpur, Dantewada, Gariyaband, and Kanker, plus West Singhbhum in Jharkhand and Kandhamal in Odisha) and slashing violent incidents by over 80% from their 2010 peak—the final push toward a Naxal-free India by March 31, 2026, faces persistent hurdles that could undermine hard-won gains if not decisively tackled.

Deep-seated distrust of state machinery lingers among tribal and rural communities, fueled by decades of historical neglect, perceived exploitation, and occasional heavy-handed operations that blur the line between security actions and rights violations, making locals skeptical of government intentions even as development accelerates. Corruption and leakages in welfare schemes—such as delayed or diverted benefits under forest rights, MGNREGA, or PMAY—continue to erode credibility, allowing extremists to exploit grievances and portray the state as indifferent or predatory.

Geographic isolation in dense, forested terrains severely hampers last-mile service delivery, infrastructure rollout (despite major road and connectivity gains), and effective governance presence, sustaining pockets where Maoists retain influence through intimidation and parallel structures. Most critically, extremist intimidation and fear of reprisals—through threats, selective violence, or labeling as informers—trap communities in a survival dilemma, preventing open cooperation with security forces or embrace of state programs and stifling the grassroots trust essential for irreversible peace.

Overcoming these intertwined challenges demands not only sustained security dominance but intensified, transparent development saturation, robust anti-corruption mechanisms, culturally attuned community engagement, and protection for those who surrender or support the mainstream to ensure no ideological vacuum remains post-eradication.

Recommendations

- Adopt an Integrated, Rights-Based Approach: Security measures, economic and social development initiatives, and human rights enforcement should be deliberately interconnected rather than siloed. For example, link community policing with skill development programs and welfare delivery to address root causes of vulnerability (e.g., unemployment or marginalization). This aligns with people-centered frameworks like UNDP’s community security model, where state and civil society actors collaborate to tackle conflict drivers while upholding rights. Prioritize joint planning forums involving security, development, and rights stakeholders to ensure policies reinforce each other and promote sustainable peace and inclusion.

- Ensure Meaningful Local Participation and Community Leadership: Actively involve community leaders, marginalized groups, and residents from the earliest stages of planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. Establish participatory mechanisms such as village-level committees or participatory audits where locals co-design interventions and provide ongoing feedback. This fosters ownership, transparency, and accountability, as emphasized in UN community engagement guidelines and rights-based approaches. Special efforts should target underrepresented voices (e.g., women, youth, and indigenous/minority groups) to build trust and avoid top-down failures.

- Prioritize Youth-Centric Policies with Focus on Education, Skills, and Employment: Center policies on youth as agents of change through comprehensive programs that combine quality education (including culturally relevant curricula), vocational skill training aligned with local job markets (e.g., in sectors like IT/ITES, agro-processing, tourism, or handicrafts in West Bengal contexts), and pathways to decent employment or entrepreneurship. Incorporate leadership development, mentorship, and community service components to build confidence and civic engagement. Evidence from models like youth-led initiatives in India shows that such integrated approaches reduce vulnerability, promote gender equity, and drive long-term community resilience.

- Strengthen Accountability through Independent and Transparent Mechanisms: Implement regular, independent audits and third-party evaluations of welfare schemes, public spending, and program outcomes to prevent misuse and ensure resources reach intended beneficiaries (especially disadvantaged groups). Combine this with public reporting, grievance redressal systems, and community monitoring tools. Draw from rights-based principles that identify “rights holders” and “duty bearers” to enhance transparency, rule of law, and corrective action, ultimately building public trust in governance.

- Embed Cultural Sensitivity and Respect for Traditions, Languages, and Identity: Design all interventions with deep respect for local traditions, languages, and cultural practices to cultivate a genuine sense of belonging and reduce alienation. This includes multilingual education, culturally responsive curricula, integration of indigenous knowledge in development projects, and avoidance of approaches that erode heritage. Such sensitivity strengthens social cohesion, empowers communities, and aligns with inclusive policies that recognize diversity as a strength rather than a barrier.

Conclusion

Winning over local people in Left Wing Extremism (LWE)-affected districts goes beyond merely suppressing violence through security operations, which can only provide temporary relief; true and enduring peace demands the creation of a just, inclusive, and participatory governance model that prioritizes holistic development, the protection of fundamental rights, and the restoration of human dignity for marginalized tribal and rural communities.

By empowering these communities as active stakeholders—through meaningful participation in planning, equitable access to education, skills training, employment opportunities, infrastructure like roads and connectivity, effective implementation of forest rights, transparent welfare delivery, and culturally sensitive approaches that respect local identities, traditions, and languages—the state can address root causes of alienation such as poverty, land disputes, governance gaps, and historical grievances.

This integrated strategy, aligning with India’s multi-pronged national policy (emphasizing security alongside development, rights enforcement, community engagement, and public perception management), transforms affected populations from passive or coerced subjects into empowered partners in India’s democratic and developmental journey, fostering sustainable trust, reducing recruitment into extremism, and paving the way for lasting social cohesion and national integration.