Introduction

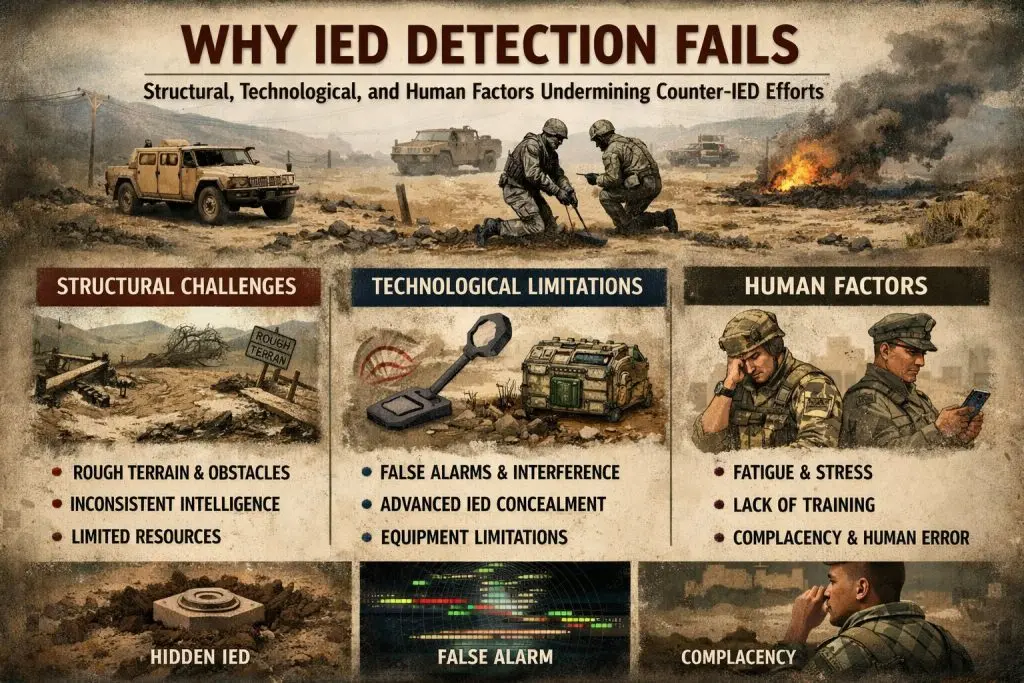

Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) are not merely weapons; they are instruments of strategic disruption. Their effectiveness lies not only in their destructive capacity but in their ability to defeat detection systems, exploit institutional weaknesses, and impose psychological dominance over security forces and civilian populations alike. Despite decades of technological advancement, training reforms, and doctrinal evolution, IED detection continues to fail with alarming regularity across conflict zones and internal security environments.

From insurgency-affected regions to urban terror settings, post-incident analyses repeatedly reveal that detection failure is rarely due to a single lapse. Instead, it is the outcome of interacting failures—technological, human, organizational, doctrinal, and environmental.

The Inherent Asymmetry of IED Warfare

Adaptive Adversaries vs. Static Defenses

IED designers operate in a continuous innovation cycle. Once a detection method becomes prevalent, adversaries modify:

- Trigger mechanisms,

- Explosive composition,

- Casing material,

- Placement tactics.

In contrast, security forces often rely on standardized equipment and rigid SOPs, creating predictability. Organizations such as NATO and FBI have consistently acknowledged that IED detection lags behind IED evolution, especially in low-intensity conflict environments.

Technological Limitations and Overreliance on Equipment

Inability to Detect Low-Metal and Plastic IEDs

Many frontline detection tools—such as handheld metal detectors (HHMDs) and deep-search metal detectors—depend on metallic signatures. Modern IEDs increasingly use:

- Plastic containers,

- Wooden casings,

- Minimal metal content,

- Carbon-based wiring.

As a result, metal-dependent detection systems provide false reassurance, allowing non-metallic IEDs to bypass checkpoints and route-clearance efforts.

Fragmented Sensor Capabilities

No single detection technology can identify:

- Explosive material,

- Trigger mechanism,

- Concealment method,

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR), chemical sensors, RF detectors, and X-ray systems each address only one dimension of the threat. Failure occurs when:

- Sensors are deployed in isolation,

- Data is not fused,

- Operators are not trained in multi-sensor interpretation.

Detection becomes mechanical rather than analytical.

False Positives and Alarm Fatigue

High false-alarm rates—caused by:

- Scrap metal,

- Soil mineralization,

- Fertilizers,

- Industrial chemicals—

lead to operator desensitization. Over time, personnel may:

- Ignore alerts,

- Reduce scan duration,

- Deviate from SOPs.

This phenomenon, known as alarm fatigue, is a critical yet under-acknowledged cause of detection failure.

Human Factors and Training Deficiencies

Inadequate Operator Training

Advanced detection equipment requires:

- Technical understanding,

- Pattern recognition skills,

- Contextual judgment.

However, in many police and paramilitary units:

- Training is equipment-centric, not threat-centric,

- Refreshers are rare,

- Operators rotate frequently.

As a result, sophisticated tools are used at a superficial level, turning detection into a ritual rather than an investigative process.

Cognitive Bias and Complacency

Repeated route clearance without incidents breeds:

- Overconfidence,

- Shortcut behavior,

- Assumption of safety.

IEDs exploit predictable human behavior more effectively than technological gaps. Historical data shows that many successful IED attacks occur:

- On “sanitized” routes,

- During routine patrols,

- After prior safe passages.

Stress, Fatigue, and Operational Pressure

IED detection often occurs under:

- Time pressure,

- Threat of ambush,

- Environmental discomfort.

Fatigue degrades:

- Attention to anomalies,

- Decision-making accuracy,

- Equipment handling discipline.

Detection failure is frequently the last link in a chain of human exhaustion.

Intelligence Failures and Information Gaps

Absence of Intelligence-Led Detection

IED detection is most effective when guided by:

- Human intelligence (HUMINT),

- Pattern-of-life analysis,

- Local community inputs.

Purely equipment-based detection is reactive. Without intelligence:

- Search areas become too broad,

- Resource allocation becomes inefficient,

- High-risk indicators are missed.

Many failures occur because detection is conducted without prior threat assessment.

Poor Inter-Agency Coordination

IED threats often cross jurisdictions involving:

- Local police,

- Intelligence agencies,

- Military or CAPFs,

- Municipal authorities.

Failures arise from:

- Delayed information sharing,

- Jurisdictional silos,

- Incompatible communication systems.

An IED undetected by one agency may have been flagged—but not shared—by another.

Environmental and Terrain Constraints

Terrain-Induced Sensor Degradation

Detection equipment performs unevenly across:

- Clay-rich soils,

- Wet or marshy ground,

- Rocky terrain,

- Urban clutter.

For example:

- GPR struggles in high-moisture soil,

- Metal detectors fail in scrap-heavy zones,

- Chemical sensors are affected by wind and heat.

IED designers deliberately exploit these environmental blind spots.

Urban Density and Civilian Presence

In urban settings:

- Background noise overwhelms sensors,

- False positives increase,

- Thorough searches are constrained by civilian movement.

Operational hesitation—driven by fear of disrupting normal life—often compromises detection rigor.

Institutional and Structural Weaknesses

Equipment Shortages and Uneven Distribution

Many districts and police commissionerates lack:

- Bomb disposal robots,

- Portable X-ray systems,

- ETDs or GPR units.

Even where equipment exists:

- Numbers are insufficient,

- Maintenance is poor,

- Accessories and spares are missing.

Detection failure here is not tactical—it is administrative.

Procurement and Standardization Issues

Delayed procurement cycles mean:

- Equipment becomes obsolete before induction,

- Training lags behind technology,

- Compatibility issues arise between systems.

Detection capabilities remain patchy and inconsistent, especially across states and regions.

Tactical Predictability and SOP Rigidity

Repetitive Search Patterns

IEDs are often planted by observing:

- Patrol timings,

- Search sequences,

- Vehicle formations.

Rigid SOPs create exploitable predictability. When adversaries know:

- Where searches slow down,

- Which areas are ignored,

- How long clearance takes,

IED placement becomes a calculated exercise.

Failure to Update SOPs Post-Incident

Post-blast inquiries frequently identify:

- Missed indicators,

- Known vulnerabilities,

- Repeated patterns.

Yet institutional inertia often prevents:

- SOP revision,

- Dissemination of lessons learned,

- Ground-level adaptation.

Thus, the same failures recur.

Neglect of Canine and Human Sensory Inputs

Despite technological advances, canine units and human intuition remain irreplaceable. Failures occur when:

- Dogs are underutilized or fatigued,

- Handlers are inexperienced,

- Human observations are overridden by machine readings.

The most effective detection systems are hybrid, not purely electronic.

Psychological and Cultural Factors

Fear of False Accusation or Public Panic

Officers may hesitate to declare suspicion due to:

- Fear of being wrong,

- Administrative scrutiny,

- Media backlash.

This hesitation delays or dilutes detection response.

Normalization of Threat

In long-running conflict zones, IED threats become:

- “Background risk”,

- Part of routine life.

This normalization dulls vigilance, making failure a matter of when, not if.

The Illusion of Technological Fixes

A critical cause of failure is the belief that:

“Better equipment alone will solve the IED problem.”

IED detection is not a purely technical challenge. It is:

- Behavioral,

- Organizational,

- Intelligence-driven,

- Context-dependent.

Technology without training, intelligence, and adaptability creates false confidence.

Conclusion

Failures in IED detection are rarely accidental. They are the predictable outcome of systemic weaknesses—technological blind spots, human limitations, intelligence gaps, environmental constraints, and institutional inertia. IEDs succeed not because detection systems do not exist, but because they are not integrated, updated, or intelligently employed.

The central lesson is clear:

IED detection fails when it is treated as a checklist activity rather than a dynamic threat-management process.

Effective counter-IED capability requires:

- Layered detection systems,

- Continuous training,

- Intelligence-led deployment,

- Flexible SOPs,

- Institutional learning cultures.

Until detection is understood as a human–technology–intelligence ecosystem, failures will persist—and adversaries will continue to exploit them.