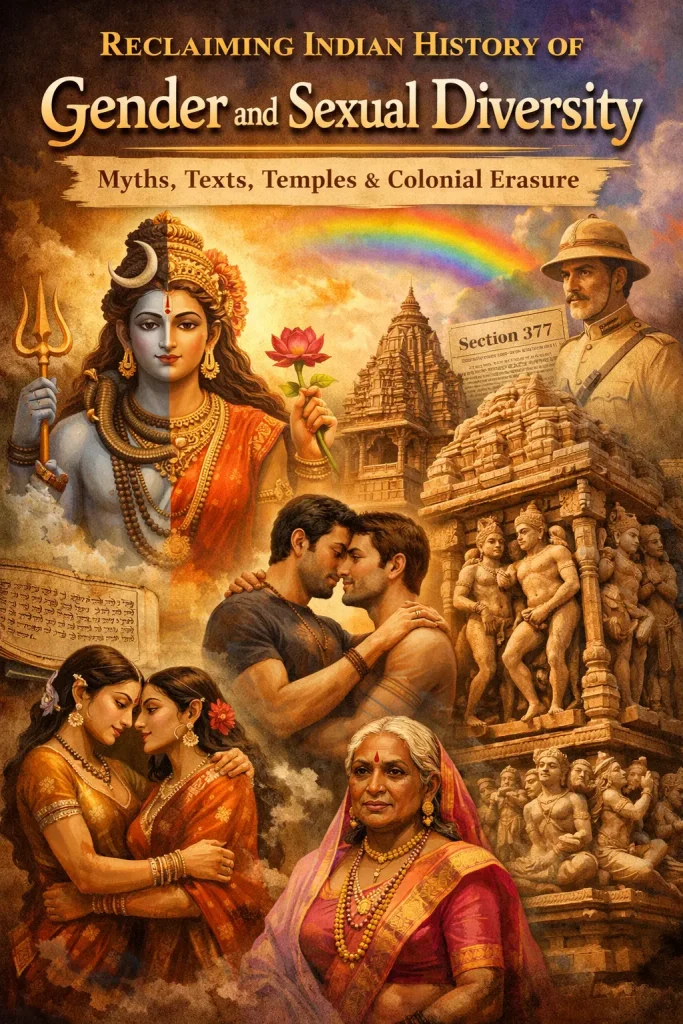

Reclaiming Indian History of Gender and Sexual Diversity

The assertion that homosexuality and gender diversity are “Western imports” alien to Indian culture has been a persistent refrain in debates about LGBTQ+ rights. This claim fundamentally misrepresents India’s rich historical and cultural traditions, which have long acknowledged diverse expressions of gender and sexuality.

From ancient texts and temple sculptures to indigenous gender systems and regional folk traditions, evidence of gender and sexual diversity permeates Indian heritage. Understanding this history is crucial not only for countering false narratives but also for reclaiming a more complete and honest account of Indian civilization.

Ancient Texts and Mythology

Indian mythology and ancient literature contain numerous references to gender fluidity, same-sex desire, and non-binary identities. These narratives, far from being marginal or condemned, are often central to religious stories and philosophical discussions.

Rigveda and Philosophical Acceptance of Diversity

The Rigveda, one of the oldest known texts, contains the hymn of Vikruti Evam Prakriti, acknowledging that what is unnatural (vikruti) is also natural (prakriti). This philosophical framework suggests an acceptance of diversity and variation as inherent to nature itself, providing a foundation for understanding difference not as deviation but as part of the natural order.

Ardhanarishvara and Divine Gender Fluidity

The concept of Ardhanarishvara—the composite form of Shiva and Parvati merged into a single body, half-male and half-female—represents perhaps the most iconic representation of gender fluidity in Hindu tradition. This form is not merely symbolic but is worshipped in temples across India, suggesting that gender transcendence was considered divine rather than deviant.

Gender Ambiguity in the Mahabharata

The Mahabharata, one of India’s great epics, contains multiple instances of gender transformation and ambiguity. Shikhandi, born female but raised male and later transformed, plays a crucial role in the war’s pivotal moment. Arjuna takes on a feminine identity as Brihannala during the year of exile. These are not minor characters or cautionary tales but central figures whose gender complexity is presented matter-of-factly.

Same-Sex Dynamics in the Ramayana

In the Ramayana, various regional versions include episodes involving same-sex dynamics. The story of Hanuman’s birth in some versions involves feminine gods who together conceive a child. The relationship between Rama and Hanuman has been interpreted by some traditions as having dimensions beyond devotion.

Puranas, Kama Sutra, and Tritiaya Prakriti

The Puranas reference tritiya prakriti—literally “third nature”—a term encompassing individuals who are neither male nor female. The Kama Sutra, the famous text on erotics, dedicates an entire chapter to same-sex practices, describing them in neutral, instructional terms without moral condemnation.

It categorizes people into different types based on their sexual preferences and practices, acknowledging diversity as a reality to be understood rather than condemned.

Divine Transformations and Fluid Identities

Stories of divine gender transformation abound. Vishnu takes the form of Mohini, a beautiful woman, to seduce demons and later even Shiva. Ila-Sudyumna alternates between male and female forms. Baghavati transforms from male to female.

These transformations are not punishments or curses but often strategic choices or natural occurrences, suggesting fluidity rather than rigid binary categories.

Temple Art and Sculptural Evidence

The sculptural traditions of India provide visual testimony to the acknowledgment of diverse sexualities and gender expressions. Temple complexes across India contain explicit representations that challenge contemporary prudishness and claims about traditional sexual mores.

Khajuraho Temples and Erotic Sculptures

The Khajuraho temples, built between 950 and 1050 CE, are famous for their erotic sculptures. Among the hundreds of figures engaged in various sexual acts are clear depictions of same-sex intimacy—women with women and men with men, presented alongside heterosexual scenes without apparent hierarchy or condemnation.

These sculptures adorn temples dedicated to major deities, suggesting that such practices were not considered antithetical to religious piety.

Konark Sun Temple and Same-Sex Eroticism

The Konark Sun Temple in Odisha, built in the 13th century, similarly contains sculptures depicting same-sex eroticism. The integration of these images into sacred architecture indicates that they were considered part of the totality of human experience worthy of artistic representation and not incompatible with the divine.

South Indian Temple Sculptures and Gender Ambiguity

Temple sculptures in South India—at sites like Gangaikonda Cholapuram and others—depict gender-ambiguous or transgender figures. Some sculptures show individuals with both male and female characteristics, while others portray gender transformation scenes from mythology.

Cultural Significance of Temple Depictions

The presence of these depictions in temple architecture is significant. Temples were not peripheral to Indian society but central institutions, and their decorative programs were carefully considered theological and cultural statements.

The inclusion of diverse sexual and gender representations suggests they were considered part of the natural and acceptable spectrum of human existence.

The Hijra Tradition

Perhaps the most visible and enduring example of institutionalized gender diversity in India is the hijra community. Hijras are individuals assigned male at birth who adopt feminine gender presentation and occupy a recognized third-gender space in Indian society.

The community has existed for millennia, with references in ancient texts and continuous historical presence through various periods.

Ritual and Social Roles of Hijras

Hijras have traditionally performed at births and marriages, offering blessings believed to bring fertility and good fortune. This ritual role indicates their integration into significant life cycle events and suggests they were considered to possess special powers or spiritual status.

Far from being outcasts, hijras historically occupied recognized positions in social and religious life.

Hijras in the Mughal Period

During the Mughal period, hijras held positions of responsibility in royal courts, harems, and administrative roles. They served as guards, advisors, and performers.

Some rose to positions of considerable power and wealth. The Mughal court’s acceptance and employment of hijras reflects a cultural accommodation of gender diversity that contrasts sharply with later colonial attitudes.

Community Structure and Traditions

The hijra community maintains its own social structures, including gurus (teachers or spiritual leaders) and chelas (disciples), territorial divisions, and ritual practices.

They undergo initiation ceremonies and often live in communes called gharanas. This complex social organization demonstrates a community with deep roots and cultural continuity.

Colonial Criminalization and Its Impact

However, the hijra community has also faced significant stigmatization, particularly following colonial interventions. The British administration, uncomfortable with gender ambiguity and perceiving hijras as immoral, enacted the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, which classified hijras as criminals.

This criminalization disrupted traditional livelihoods and social positions, forcing many into begging and sex work.

Contemporary Challenges and Resilience

Contemporary hijra communities continue to face marginalization despite recent legal recognition. The traditional ritual roles have diminished, and economic opportunities remain limited.

Many face violence, police harassment, and social exclusion. Yet the community persists, maintaining traditions and asserting identity in the face of ongoing discrimination.

Regional Folk Traditions

Beyond Sanskrit texts and courtly culture, regional folk traditions across India contain rich examples of gender diversity and same-sex relationships.

These traditions, often overlooked in dominant historical narratives, reveal the depth and breadth of sexual and gender diversity in Indian culture.

Koovagam Festival in Tamil Nadu

In Tamil Nadu, the Koovagam festival celebrates the story of Aravan, who married Krishna (in his Mohini form) before sacrificing himself.

Transgender women and male-assigned persons gather annually to enact this marriage, followed by ritual widowhood. This festival, attended by thousands, demonstrates the continuation of mythological traditions that honor gender transformation and same-sex relationships.

Jogappa Tradition in Karnataka

The jogappa tradition in Karnataka involves individuals assigned male at birth who become devoted to the goddess Yellamma and adopt feminine dress and roles.

They are considered auspicious and perform at religious functions. This tradition reflects the integration of gender diversity into religious practice at the community level.

Gotipua Tradition in Odisha

In Odisha, the gotipua tradition involves young boys dancing in feminine attire and ornaments, performing classical Odissi dance.

While sometimes explained as merely performance, the tradition involves sustained gender-crossing and has been read by some scholars as reflecting more complex understandings of gender.

Folk Narratives and Oral Traditions

Folk narratives from various regions include stories of same-sex love, gender transformation, and characters who don’t fit male-female binaries.

These stories, transmitted orally and often not documented in written form until recently, represent grassroots cultural production that challenges claims about uniform heteronormativity in Indian traditions.

Sufi Traditions and Gender Ambiguity

Certain Sufi traditions in the subcontinent also acknowledged and celebrated gender ambiguity and same-sex desire.

Sufi poetry often employs homoerotic imagery, and some Sufi saints were known for relationships with male disciples that transcended typical teacher-student bonds.

Qawwali performances sometimes involved gender-crossing and celebration of diverse desires.

Colonial Impact: Inventing Tradition

The British colonial period fundamentally transformed Indian attitudes toward sexuality and gender. Victorian morality, Christian sexual ethics, and colonial legal frameworks imposed new rigidities and created the criminalization framework that would last into the 21st century.

Section 377 and Colonial Morality

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, enacted in 1860, criminalized “carnal intercourse against the order of nature.” This provision was based on British buggery laws and reflected Victorian Christian morality rather than indigenous Indian legal or moral traditions.

The term “unnatural” imposed a judgment alien to the more fluid conceptual frameworks evident in Indian texts and traditions.

Colonial Anthropology and Ethnography

Colonial anthropology and ethnography documented Indian sexual and gender diversity through judgmental lenses. British administrators, missionaries, and scholars described hijras, gender-diverse individuals, and same-sex practices in terms of deviance, criminality, and immorality.

These colonial texts created official narratives that pathologized what earlier traditions had accommodated.

Creation of Fixed Sexual Identities

The colonial legal system not only criminalized certain acts but also created new categories of identity centered on sexual practices. The notion of “the homosexual” as a fixed identity category emerged in the West in the 19th century and was imported to India through colonial frameworks.

This was different from earlier Indian conceptualizations that focused more on practices, roles, and contexts than fixed sexual identities.

Colonial Education and Textual Selection

Colonial education systems promoted Victorian ideals of gender and sexuality, teaching that men and women occupied separate spheres with rigid behavioral norms.

Traditional Indian texts that acknowledged sexual and gender diversity were either ignored or reinterpreted to minimize such elements. The selective reading and translation of Sanskrit texts emphasized aspects compatible with Victorian morality while downplaying or censoring others.

Reform Movements and Respectability Politics

Indian reformers and nationalists, educated in colonial systems and seeking respectability in colonial eyes, sometimes adopted Victorian sexual morality.

The reform movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries often embraced conservative sexual ethics as part of constructing a “respectable” Indian identity. This adoption of colonial values has been misremembered as traditional Indian morality.

Invented Traditions and Cultural Erasure

The construction of “Indian tradition” during the colonial and nationalist periods thus involved selective emphasis on certain texts and practices while erasing others.

- Heteronormative family structures

- Rigid gender roles

- Sexual conservatism

The diversity evident in historical sources was replaced by narratives emphasizing these elements. This invented tradition has been so successful that many Indians today believe Victorian morality represents ancient Indian values.

Post-Independence Trajectories

Following independence in 1947, India inherited not just colonial laws but also colonial attitudes toward sexuality and gender. The continuity of Section 377 in the Indian legal code represented the persistence of colonial morality encoded in law.

Early post-independence decades saw little challenge to these frameworks, as nation-building priorities focused elsewhere.

The Hindu Right and Colonial Legacy

The Hindu right, which gained political prominence from the 1980s onward, ironically embraced colonial constructions of Indian tradition while claiming to defend indigenous culture.

The assertion that homosexuality is Western and alien to Indian culture represents a profound historical amnesia, forgetting or deliberately erasing the evidence of diversity in Indian heritage.

Academic Recovery of Erased Histories

Academic scholarship from the 1980s onward began recovering historical evidence of sexual and gender diversity in Indian traditions.

- Textual evidence

- Sculptural evidence

- Folk traditions

Scholars documented material that challenged dominant narratives and provided historical grounding for contemporary LGBTQ+ rights movements.

LGBTQ+ Activism and Cultural Reclamation

The emergence of organized LGBTQ+ activism in India from the 1990s included efforts to reclaim historical and cultural heritage.

Activists and scholars worked to make visible the erased histories, arguing that acceptance of diversity was more authentically Indian than Victorian prudishness.

This reclamation work served two key purposes:

- Countering claims about Western influence

- Providing affirming narratives for LGBTQ+ Indians seeking cultural belonging

Contemporary Cultural Production

Contemporary Indian queer artists, writers, filmmakers, and performers are creating cultural work that both draws on historical traditions and speaks to present realities.

This cultural production serves multiple functions:

- Artistic expression

- Political statement

- Community building

- Historical recovery

Queer Literature in India

Literature by LGBTQ+ Indian writers has flourished in recent decades, encompassing fiction, poetry, and drama that explore queer experiences in Indian contexts.

These works often engage with both contemporary realities and historical traditions, weaving together personal narratives and cultural heritage.

Regional Language Queer Writing

In regional languages, queer literature is emerging, though often with less visibility than English-language work.

- Marathi

- Bengali

- Tamil

- Malayalam

These literatures now include openly queer voices, expanding the linguistic and cultural diversity of Indian queer expression.

Film and Documentary Representation

Film has been a powerful medium for queer representation, though not without controversy. Some films sparked both critical acclaim and violent protests, while others brought LGBTQ+ stories to mainstream audiences.

Documentary films have documented community histories, legal battles, and personal journeys, contributing to public awareness and historical record.

Theatre and Performance Spaces

Theatre has provided space for queer expression, with plays exploring:

- Coming out

- Discrimination

- Desire

- Identity

Queer theatre festivals have emerged, creating venues for experimentation and community building.

Visual Art and Public Expression

Visual artists have used photography, painting, installations, street art, and graffiti to explore queer themes.

These works engage with mythology, history, and contemporary politics while making queer presence visible in public spaces.

Performance, Drag, and Music Cultures

Queer South Asian performance and drag cultures have developed distinctive styles, drawing on Indian aesthetic traditions while creating contemporary forms.

Music and spoken word by LGBTQ+ artists express diverse experiences, ranging from political protest to love, desire, and celebration.

Academic and Activist Scholarship

The recovery and interpretation of queer histories in India has been a joint project of academics and activists, often the same individuals occupying both roles. This scholarship serves multiple purposes—historical recovery, theoretical development, and political intervention.

Early Documentation of Queer Histories

Early work focused on documenting evidence from texts, inscriptions, and sculptures. Scholars combed through Sanskrit literature, temple records, and folk traditions, making visible what had been erased or ignored.

- Translations and analyses of specific texts like the Kama Sutra

- Sections of the Mahabharata

- Puranic stories highlighting same-sex and gender-diverse content

Theoretical Debates and Interpretive Frameworks

Theoretical work has engaged with how to interpret historical evidence. Questions arise about applying contemporary categories like “homosexual” or “transgender” to historical periods with different conceptual frameworks.

- Some scholars argue for using indigenous terminology like tritiya prakriti

- Others employ contemporary global categories

These debates reflect broader tensions in queer studies about universalism versus cultural specificity.

Colonial Impact on Sexual Norms

Work on colonial impact has been crucial in understanding how contemporary attitudes developed. Scholars have shown how British colonialism imposed Victorian morality, created new legal frameworks of criminalization, and influenced nationalist constructions of tradition.

This scholarship undermines claims that hostility to LGBTQ+ persons represents authentic Indian tradition.

Intersectional Approaches to Queer History

Intersectional approaches examine how sexuality and gender interact with caste, class, religion, and region.

- Dalit queer experiences

- Muslim LGBTQ+ lives

- Regional variations in gender and sexuality

This scholarship has complicated simplistic narratives about Indian queerness, revealing diversity within diversity.

Ethnographic Work and Living Traditions

Contemporary ethnographic work documents living traditions and communities—hijras, kothis, aravanis, and other indigenous gender and sexual categories.

This work shows the continuation of diverse gender systems alongside the impact of globalization and changing economic structures on these communities.

Challenges in Historical Recovery

The project of recovering queer histories in India faces several challenges.

Limitations of Sources

- Source materials are limited, as many traditions were oral rather than textual

- Documentation was selective and often exclusionary

- Colonial period records reflect colonial biases

- Post-independence scholarship often minimized or ignored sexual and gender diversity

Risks of Interpretation and Anachronism

Interpretation of historical evidence requires care. Not all gender transformation in mythology should be read as transgender identity, and not all same-sex intimacy in texts represents what we now call homosexuality.

Historical contexts differ from contemporary ones, and imposing present categories on the past risks anachronism. However, the opposite risk—refusing to see continuities and connections—also distorts history.

Knowledge Hierarchies and Textual Bias

The selectivity of which texts and traditions are considered authoritative creates challenges.

- Sanskrit texts from elite, Brahmanical traditions receive more attention

- Folk traditions, regional languages, and oral narratives are underrepresented

This bias reflects caste and class hierarchies in knowledge production. Recovering histories of non-elite queer lives requires different methodologies and sources.

Political Instrumentalization of History

Political instrumentalization of historical recovery poses another challenge. Both LGBTQ+ activists and conservative opponents selectively cite history to support their positions.

The nuances of historical evidence—that ancient India was neither uniformly accepting nor uniformly hostile—often get lost in polarized debates seeking simple answers to complex questions.

Reclaiming vs. Romanticizing

While recovering queer histories is important, it requires avoiding romanticization. Ancient and medieval India were not queer utopias.

- Acknowledgment of diversity coexisted with patriarchy

- Caste oppression and other forms of hierarchy and violence persisted

Gender diversity in texts did not necessarily translate to lived equality for gender-diverse people.

Historical Position of the Hijra Community

The hijra community, while historically visible, has never enjoyed full social equality. They occupied specific ritual roles but also faced violence and marginalization.

Their current situation reflects both historical continuities and colonial disruptions, and the notion of a golden age of acceptance oversimplifies reality.

Artistic Representation vs. Social Practice

Temple sculptures depicting same-sex eroticism do not necessarily indicate that same-sex relationships were socially acceptable in practice.

Erotic art often depicts fantasies and ideals rather than social realities. The gap between artistic representation and lived experience must be acknowledged.

Mythology and Lived Experience

Mythological gender fluidity does not automatically translate to acceptance of actual gender-diverse individuals. The divine can transgress boundaries denied to humans.

What is celebrated in gods may be punished in mortals. The distance between mythology and social practice must be recognized.

Purpose of Historical Recovery

The purpose of historical recovery is not to prove that ancient India was perfect but to challenge false claims that diversity is alien to Indian culture.

The evidence shows that Indian traditions have long acknowledged, represented, and sometimes celebrated sexual and gender diversity, even if this coexisted with regulation, hierarchy, and sometimes oppression.

Contemporary Debates and Uses of History

Contemporary debates about LGBTQ+ rights in India frequently invoke history and culture. Opponents argue that accepting LGBTQ+ rights violates Indian culture and tradition. Supporters counter by citing evidence of historical diversity. These debates reveal underlying questions about who defines culture, which traditions are authoritative, and how history should inform present policy.

Selective Invocation of Tradition

Conservative opposition often selectively invokes religious texts while ignoring evidence of diversity in the same traditions. Citations of Manusmriti or other prescriptive texts are offered as proof of traditional condemnation, while mythological stories of gender transformation are dismissed as metaphorical. This selectivity reflects contemporary politics rather than balanced engagement with tradition.

History as a Tool for Rights Claims

LGBTQ+ advocates use historical evidence to argue that acceptance of diversity is more authentically Indian than Victorian prudishness imposed by colonialism. This framing appeals to cultural nationalism while supporting rights claims. However, it risks suggesting that rights depend on historical precedent rather than being inherent to human dignity.

Contested Interpretations of Tradition

The question of whose interpretation of tradition should prevail remains contested. Religious authorities, scholars, activists, and ordinary citizens offer competing readings of texts and practices. Democratic societies must navigate these competing claims while protecting individual rights regardless of historical debates.

Law and Historical Acknowledgment

Legal arguments have sometimes invoked historical evidence. The 2018 Supreme Court judgment decriminalizing homosexuality referenced historical traditions acknowledging diversity, though the decision ultimately rested on constitutional rights rather than historical practice. The acknowledgment of historical diversity supported the court’s rejection of claims that homosexuality is alien to Indian culture.

Beyond Binary Recovery

Recent scholarship and activism increasingly recognize that recovering queer histories requires moving beyond binary frameworks. The project is not simply proving that “homosexuality existed in ancient India” but understanding more complex systems of gender and sexuality that don’t map neatly onto contemporary categories.

Indigenous Categories and Local Understandings

Indigenous categories like hijra, kothi, panthi, and others represent locally specific understandings of gender and sexuality that don’t perfectly align with Western categories of transgender, gay, or bisexual. Respecting these categories while also acknowledging connections to global LGBTQ+ identities requires nuanced approaches.

- Hijra

- Kothi

- Panthi

- Others representing locally specific identities

Multiplicity Within Indian Traditions

The diversity within Indian traditions—across regions, languages, castes, and time periods—means there is no single “Indian tradition” regarding sexuality and gender. Attempting to construct unified narratives oversimplifies. Instead, acknowledging multiplicity and variation more accurately represents historical reality.

Hybrid Identities and Contemporary Queer Politics

Contemporary Indian queer movements draw on both global LGBTQ+ frameworks and indigenous traditions, creating hybrid identities and politics. This synthesis reflects the reality of living in a globalized world while being rooted in specific cultural contexts. Neither purely “traditional” nor simply “Western,” contemporary Indian queerness creates new formations.

Conclusion

The claim that homosexuality and gender diversity are Western imports alien to Indian culture crumbles under historical scrutiny. From Vedic texts and Puranic stories to temple sculptures and folk traditions, from the hijra community to regional gender systems, evidence of sexual and gender diversity permeates Indian heritage. This diversity was acknowledged, represented, and integrated into religious and social life in complex ways that defy simplistic narratives of either uniform acceptance or condemnation.

Colonial Legacy and Misremembered Tradition

The colonial period imposed new frameworks of criminalization and pathologization rooted in Victorian Christian morality rather than indigenous Indian traditions. This colonial legacy, misremembered as authentic Indian culture, has shaped contemporary hostility to LGBTQ+ rights. Recognizing this history challenges false dichotomies between Indian culture and LGBTQ+ rights.

Why Recovering Queer Histories Matters

Recovering queer histories in India serves multiple purposes.

- It counters false narratives about cultural authenticity.

- It provides affirming historical narratives for LGBTQ+ Indians seeking to reconcile identity with cultural belonging.

- It enriches our understanding of Indian civilization by making visible erased dimensions of cultural heritage.

- It challenges the presumption that contemporary global LGBTQ+ identities are purely Western constructs without resonance in other traditions.

Limits and Cautions in Historical Interpretation

However, historical recovery must avoid romanticization and instrumentalization. Ancient India was neither queer utopia nor universally hostile space. Evidence must be interpreted carefully, acknowledging complexities and avoiding anachronism. The purpose is not to prove that history dictates present policy but to challenge false claims and expand our understanding of human diversity across time and culture.

Rights Grounded in Dignity, Not Just History

Ultimately, the case for LGBTQ+ rights rests on principles of human dignity, equality, and freedom rather than historical precedent. Yet history matters in cultural debates about identity and belonging. For LGBTQ+ Indians, knowing that their existence is not alien to Indian culture but part of its rich tapestry provides affirmation. For society, recognizing this history challenges prejudice rooted in colonial constructions masquerading as tradition.

The Ongoing Project of Reclamation

The project of reclaiming queer histories in India continues, as new scholarship uncovers additional evidence and reinterprets known materials. Contemporary artists, activists, and scholars create work that draws on historical traditions while speaking to present realities. This ongoing engagement with heritage, far from being backward-looking, enriches contemporary culture and strengthens claims for justice and equality. It demonstrates that diversity is not foreign to Indian tradition but integral to it, woven into the fabric of civilization from ancient times to the present.