Foundational Pillars of India’s Free and Fair Elections

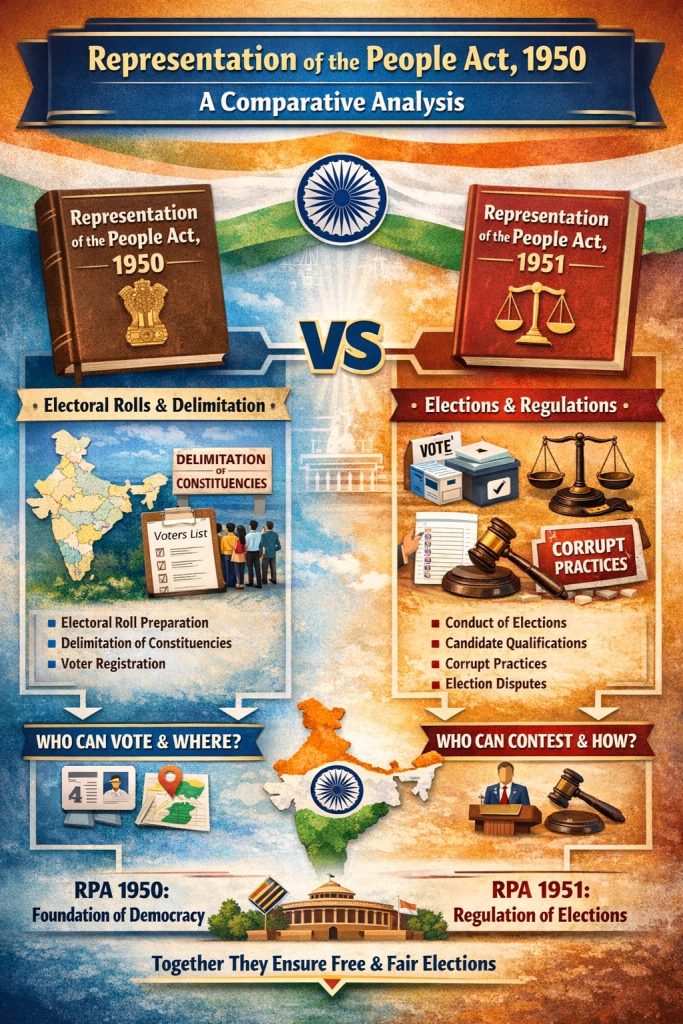

Free and fair elections are the cornerstone of a democratic polity. In India, the constitutional vision of representative democracy under Articles 324 to 329 is operationalised primarily through two key legislations: the Representation of the People Act, 1950 and the Representation of the People Act, 1951. Though often mentioned together, the two Acts serve distinct yet complementary purposes within the electoral framework. While the Act of 1950 lays the foundation of electoral democracy, the Act of 1951 regulates its actual functioning and integrity.

This article critically examines both Acts, highlighting their objectives, scope, and key differences, while underscoring their collective role in strengthening Indian democracy.

Constitutional Background

The Indian Constitution mandates elections to the Parliament and State Legislatures to be conducted on the basis of adult suffrage (Article 326) and under the superintendence, direction, and control of the Election Commission of India (Article 324). However, the Constitution itself provides only a broad framework and leaves operational details to Parliament. To give effect to these constitutional provisions, Parliament enacted: Representation of the People Act, 1950, and Representation of the People Act, 1951

Each Act addresses different stages of the electoral process.

Representation of the People Act, 1950: Laying the Electoral Foundation

The RPA, 1950 primarily deals with the pre-electoral structure necessary for conducting elections. Its central concern is to ensure that every eligible citizen is properly registered as a voter and assigned to a constituency.

Key Features of RPA, 1950

- Delimitation and Allocation of Seats: The Act provides for the allocation of seats in the House of the People (Lok Sabha) and State Legislative Assemblies, and for the delimitation of constituencies based on population.

- Electoral Rolls: A major focus of the Act is the preparation, revision, and maintenance of electoral rolls, including: Qualifications for registration as a voter, Disqualifications such as non-citizenship or unsoundness of mind, and Procedures for correction, inclusion, and deletion of names

- Electoral Machinery: It establishes the administrative machinery for voter registration, such as Electoral Registration Officers and Assistant Electoral Registration Officers

- Equality and Universal Adult Franchise: The Act operationalises Article 326 by ensuring that every eligible citizen above 18 years is given the opportunity to be enrolled without discrimination.

Nature of the Act

The RPA, 1950 is administrative and preparatory in nature. It does not deal with candidates, political parties, or election conduct.

Representation of the People Act, 1951: Regulating Electoral Competition

The RPA, 1951 governs the actual conduct of elections and ensures the purity of the electoral process. It comes into operation once the electoral groundwork has been laid by the 1950 Act.

Key Features of RPA, 1951

- Conduct of Elections: The Act provides detailed provisions relating to Notification of elections, filing of nominations, scrutiny and withdrawal, polling and counting of votes, and Declaration of results

- Qualifications and Disqualifications of Candidates

It prescribes qualifications for contesting elections and lists disqualifications such as Conviction for certain criminal offences, Corrupt practices, and Failure to lodge election expense accounts

- Corrupt Practices and Electoral Offences: To safeguard electoral integrity, the Act defines corrupt practices including bribery, undue influence, misuse of government machinery, hate speech and appeal on religious grounds.

- Election Expenditure: The Act imposes limits on election expenses to ensure a level playing field and curb money power in politics.

- Election Petitions and Dispute Resolution: It lays down procedures for challenging election results through election petitions filed in High Courts.

- Recognition of Political Parties: Provisions related to the registration and regulation of political parties flow from this Act and related rules.

Nature of the Act

The RPA, 1951 is regulatory, legal, and punitive in nature, aimed at ensuring fairness, transparency, and accountability.

Key Differences Between RPA, 1950 and RPA, 1951

|

Dimension |

RPA, 1950 |

RPA, 1951 |

|

Core Objective |

Electoral rolls and constituency delimitation |

Conduct and regulation of elections |

|

Primary Focus |

Voters and constituencies |

Candidates, parties, and election process |

|

Nature |

Administrative |

Legal and regulatory |

|

Corrupt Practices |

Not covered |

Explicitly defined and penalised |

|

Election Disputes |

No provision |

Detailed mechanism for election petitions |

|

Election Expenses |

Not included |

Regulated and monitored |

|

Applicability Stage |

Pre-election |

During and post-election |

Complementary Role in Democratic Governance: The two Acts function as two pillars of the electoral system: without the RPA, 1950, elections would lack an accurate voter base and clearly defined constituencies and without the RPA, 1951, elections would be vulnerable to malpractice, criminalisation, and disputes without legal remedies. Together, they ensure that elections are inclusive, competitive, transparent, and legitimate.

Contemporary Relevance and Challenges: In recent times, issues such as criminalisation of politics, use of money and muscle power, misuse of digital platforms, demand for electoral reforms, and independence of Election Commission have brought renewed focus on the effective implementation and reform of the Representation of the People Act, especially the 1951 Act. Judicial interventions and Election Commission guidelines have played a crucial role in strengthening these laws.

Key Electoral Offences: RPA 1950 & 1951

|

Act |

Sections |

Nature of Offences in Brief |

|

RPA, 1950 |

31, 32 |

Electoral Roll Misconduct: Making false declarations regarding entries in the electoral roll and breach of official duty by registration officers. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

123 |

Corrupt Practices: Includes bribery, undue influence, appeals based on religion/caste/community, and the use of government machinery for campaigning. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

125 |

Promoting Enmity: Promoting or attempting to promote feelings of enmity or hatred between different classes of citizens on grounds of religion, race, or language. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

126 |

Violation of Silence Period: Prohibition of public meetings and campaigning during the 48 hours ending with the hour fixed for the conclusion of the poll. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

127 |

Disturbances at Meetings: Creating disturbances at election meetings to prevent the transaction of business. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

134 |

Official Duty Breach: Any person on election duty found in breach of their official duties without reasonable cause. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

134A |

Public Servant Misconduct: Specific penalty for Government servants acting as an election agent, polling agent, or counting agent. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

135 |

Removal of Ballots: Fraudulently or without authority taking ballot papers out of a polling station. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

135A |

Booth Capturing: Seizing a polling station, preventing voters from voting, or forcing the presiding officer to surrender ballot papers/machines. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

136 |

Fraudulent Acts: Tampering with nomination papers, ballot boxes, or official marks; general fraudulent acts at elections. |

|

RPA, 1951 |

138–139 |

General Penalties: Jurisdiction and legal procedures for the prosecution of electoral offences and penalties for public servants. |

Together, these sections form the core penal framework ensuring discipline, fairness, and integrity in India’s electoral process.

Section 135A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (Booth Capturing) is the most stringent penal provision under the Act and is expressly classified as cognizable and may be non-bailable. This empowers law-enforcement agencies to arrest immediately without a warrant of arrest and denies the automatic right to bail, reflecting the grave threat booth capturing poses to the sanctity of the ballot and the democratic process. All other offences under the Representation of the People Act, 1950 and the Representation of the People Act, 1951 are generally bailable and non-cognizable, unless the conduct also constitutes non-bailable offence under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS).

In Indian electoral law, a vital distinction exists between Corrupt Practices and Electoral Offences, primarily defined by their legal consequences and the courts that handle them.

Corrupt Practices, governed by Section 123 of the RPA 1951, are essentially civil-electoral wrongs; they are adjudicated by a High Court through an Election Petition and focus on the validity of the victory itself. If proven, the candidate’s election is declared void, and they face a mandatory six-year disqualification from contesting future elections.

On the other hand, Electoral Offences (Sections 125–136) are strictly criminal acts that trigger immediate prosecution in a criminal court. While a corrupt practice mainly threatens a candidate’s political career, an electoral offence carries the weight of criminal law, leading to imprisonment or fines for any individual involved, irrespective of whether they won the election or even contested it.

Decriminalization of Politics: Disqualification under Section 8

Section 8 of the RPA 1951 is designed to safeguard the sanctity of the legislature by barring individuals with criminal backgrounds. Disqualification is applied through a graded approach: Section 8(1) triggers an immediate bar for serious social or national offences (like rape or bribery) upon any conviction; Section 8(2) applies to socio-economic crimes (like hoarding) with a minimum six-month sentence; and Section 8(3) covers all other offences resulting in at least two years of imprisonment.

This legal barrier begins on the date of conviction and extends for a further six years after the individual’s release from prison, ensuring that those who breach the law are excluded from the law-making process for a significant duration.

As of January 2026, Section 8(4) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 continues to remain struck down following the Supreme Court’s 2013 Lily Thomas judgment, with no legislative restoration or major amendment to the core framework of the 1950 and 1951 Acts having occurred despite persistent debates and reform proposals on criminalisation of politics.

The Role of the High Court (Section 80A)

Under the Representation of the People Act (RPA), 1951, the High Court serves as the primary judicial authority for resolving disputes related to the validity of an election.

The High Court has original jurisdiction to try election petitions. This means you do not start in a lower court; the challenge begins directly at the High Court of the state where the election took place.

Presiding Judge: The jurisdiction is typically exercised by a Single Judge assigned by the Chief Justice of that High Court.

Powers of the Court: During the trial, the High Court acts as a neutral arbiter with the power to declare an election void if corrupt practices or legal irregularities are proven, declare a new winner if the court finds that the petitioner or another candidate actually received the majority of valid votes, and Order Recounts: If there is evidence of miscounting or improper rejection of votes.

Finality & Communication: Once the trial concludes, the High Court must immediately notify the Election Commission of India (ECI) and the Speaker or Chairperson of the relevant House (Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha, or State Assembly).

Timeline and Procedure for Filing

Strict adherence to timelines is mandatory in electoral law. Even a single day’s delay can lead to the dismissal of a petition.

|

Requirement |

Details |

|

Limitation Period |

An election petition must be filed within 45 days from the date of the declaration of the results. |

|

Who Can File? |

Any candidate who contested that election or any elector (voter) registered in that constituency. |

|

Grounds (Section 100) |

Petitions can be filed based on disqualification of the winner, commission of corrupt practices, improper rejection/acceptance of nominations, and non-compliance with the Constitution or the RPA. |

|

Security Deposit |

The petitioner must deposit ₹2,000 (amount may vary by specific High Court rules) as security for the costs of the petition. |

|

Trial Duration |

The RPA recommends that the High Court endeavour to conclude the trial within 6 months, though in practice, it often takes longer. |

|

Appeal to Supreme Court |

Any party aggrieved by the High Court’s decision can appeal to the Supreme Court within 30 days of the order. |

Why the 45-Day Window Matters

The 45-day deadline is “sacrosanct.” Under Section 81, if a petition is filed on the 46th day, the court generally has no power to condone the delay, as the Limitation Act does not apply to election petitions in the same way it does to civil suits. This ensures that the cloud of uncertainty over an elected representative’s status is cleared quickly.

Summary of Landmark Supreme Court Judgments

|

Case Name |

Core Ruling |

Legal Impact |

|

ADR Case (2002) |

Mandatory disclosure of candidate background. |

Established the “Right to Know” for voters. |

|

Lily Thomas (2013) |

Struck down Sec 8(4) of RPA 1951. |

Ended the 3-month protection; instant disqualification on conviction. |

|

PUCL (NOTA) (2013) |

Directed the inclusion of “None of the Above.” |

Right to register negative opinion against all candidates. |

|

Public Interest Foundation (2018) |

Compulsory media publicity of criminal cases. |

Shifted the burden of “cleaning politics” to parties and voters. |

Conclusion

The RPA 1950 and 1951 form the bedrock of Indian democracy, translating constitutional ideals into practice. The 1950 Act is administrative, establishing the voter base through electoral rolls and constituency delimitation. Conversely, the 1951 Act is regulatory and punitive, governing candidate conduct, election management, and dispute resolution via High Courts. Together, they ensure a seamless transition from preparation to execution.

However, contemporary challenges like criminalization and technological shifts necessitate robust enforcement and alignment with the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023. Ultimately, their success relies on faithful implementation to preserve the sanctity of the ballot and the democratic will.