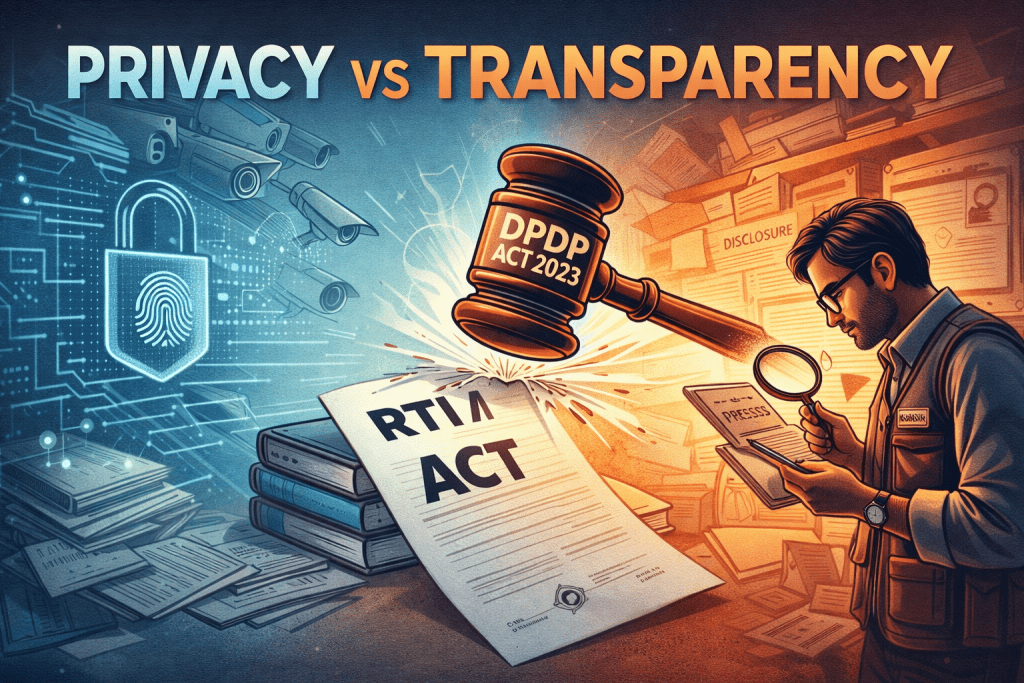

Background of the Challenge

Three separate Public Interest Litigations (PILs) have been filed before the Supreme Court challenging the constitutional validity of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDP Act) and the Rules notified under it. The petitioners argue that while the legislation claims to safeguard digital privacy, it simultaneously undermines the Right to Information (RTI), hampers investigative journalism, and expands the scope of state surveillance. The Court has admitted the petitions, issued notice to the Union government, and referred the matter to a Constitution Bench of five judges for hearing. However, it has declined to grant an interim stay on the operation of the Act.

Who Filed the Petitions

The petitions have been filed by the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information (NCPRI), transparency advocate Venkatesh Nayak, and The Reporters’ Collective (TRC) Trust, a body of investigative journalists. Their central grievance concerns the amendment introduced by Section 44(3) of the DPDP Act to Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act, 2005. This provision governs the disclosure of personal information held by public authorities.

Petitioners at a Glance

- National Campaign for People’s Right to Information (NCPRI)

- Venkatesh Nayak (Transparency Advocate)

- The Reporters’ Collective (TRC) Trust

Original RTI Framework

Under the original framework of the RTI Act, personal information could be denied only if it had no relationship to any public activity or public interest, or if disclosure would result in an “unwarranted invasion” of an individual’s privacy. Importantly, the law contained a public interest override. A Public Information Officer (PIO) retained the discretion to disclose even personal information if satisfied that the larger public interest justified such disclosure. This mechanism ensured a balance between privacy and transparency, particularly in matters involving public officials and the use of public resources.

RTI Balancing Mechanism

- Privacy protection for individuals

- Public interest override available

- PIO discretion to disclose information

- Accountability of public officials maintained

Changes Introduced by DPDP Act

The amendment brought by the DPDP Act removes this public interest override. Petitioners argue that this effectively extinguishes the statutory power of the PIO to weigh competing considerations of privacy and public interest. By doing so, it creates what they describe as an “absolute bar” on disclosure of personal information, regardless of its relevance to public accountability. According to NCPRI, this change converts a carefully calibrated privacy exemption into a sweeping shield that could protect corrupt officials from scrutiny.

Comparison: Before and After Amendment

| Aspect | RTI Act (Original) | After DPDP Amendment |

|---|---|---|

| Public Interest Override | Available | Removed |

| PIO Discretion | Can disclose in larger public interest | Effectively eliminated |

| Transparency | Balanced with privacy | Strong tilt toward secrecy |

| Accountability | Enables scrutiny of public officials | May shield wrongdoing |

Impact on Journalism

The impact on journalism forms another major plank of the challenge. TRC contends that investigative reporting often relies on access to documents such as asset declarations, tender records, and official file notings materials that frequently contain personal data. By eliminating the public interest override, authorities may deny access to such records, even when they reveal wrongdoing or misuse of public funds. The petitioners argue that this would significantly weaken the press’s role as a watchdog in a constitutional democracy.

Documents Commonly Used in Investigations

- Asset declarations

- Tender records

- Official file notings

- Public fund utilisation records

Constitutional Arguments

All three petitions invoke the Supreme Court’s 2017 judgment in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India, which recognized the right to privacy as a fundamental right and laid down the proportionality test for restrictions on fundamental freedoms. They contend that while protecting privacy is a legitimate aim, the removal of the balancing mechanism fails the proportionality standard. The amendment, they argue, is excessive and arbitrary because it sacrifices transparency without adequate safeguards.

Legal Principles Invoked

- Right to privacy as a fundamental right

- Proportionality test

- Balancing of competing rights

- Protection against arbitrary state action

A Constitutional Crossroads

The case thus presents a constitutional crossroads between two foundational democratic values: privacy and transparency. The forthcoming decision of the Constitution Bench will determine whether the data protection regime can coexist with the right to information or whether the balance will tilt decisively in favour of secrecy. The outcome is likely to have lasting implications for open governance, public accountability, and press freedom in India.