Introduction

Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) remain one of the most persistent and devastating weapons in asymmetric warfare, insurgencies, and terrorism. These homemade devices—assembled from civilian or dual-use materials—are designed to cause mass casualties and psychological terror. A standard IED comprises an explosive charge, initiator, power source, switch, and container, often augmented with shrapnel (nails, ball bearings, glass, scrap metal) to maximize lethality.

IEDs have profoundly shaped conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, and Left-Wing Extremism (LWE)-affected districts in India. Their impact extends well beyond immediate casualties, inflicting severe long-term physical, psychological, societal, economic, strategic, and environmental damage.

- Mechanisms of Harm from IED Explosions

An IED detonation rapidly converts the explosive charge into superheated, high-pressure gas, generating a supersonic shock wave (blast overpressure) that propagates outward, causing harm through multiple mechanisms:

- Primary injuries: Direct effects of blast overpressure on air-filled organs. These include “blast lung” (pulmonary barotrauma with tearing, fluid/blood accumulation, and collapse), tympanic membrane rupture, and gastrointestinal perforation. Injuries may be invisible externally but life-threatening.

- Secondary injuries: Penetrating trauma from propelled fragments/shrapnel, causing lacerations, amputations, deep wounds, and high infection risk due to contamination.

- Tertiary injuries: Displacement of the body by blast wind, leading to blunt trauma such as fractures, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and crush injuries from structural collapse.

- Quaternary injuries: Thermal (burns), chemical (inhalation of smoke/toxins), asphyxiation, and exacerbation of pre-existing conditions.

- Quinary injuries: Systemic hyperinflammatory responses triggered by unconventional additives (e.g., chemicals, radiological material), manifesting as fever, severe inflammation, and complicated recovery unrelated to visible trauma severity.

Victims frequently sustain combined injuries, complicating triage and treatment.

- Common Physical Injuries

- Pulmonary and thoracic: Blast lung remains a leading cause of death; survivors often face chronic respiratory issues.

- Musculoskeletal: Roadside/vehicle blasts frequently cause lower-limb amputations, open fractures, spinal damage, and pelvic/genital trauma (potentially leading to infertility, chronic pain, and psychological distress).

- Neurological: Traumatic brain injury (even without external wounds), resulting in cognitive deficits, memory loss, mood disorders, headaches, and neuropathy.

- Sensory: Ocular rupture/blindness, tympanic rupture (eardrum tearing), hearing loss, tinnitus (constant ringing in the ears), and vestibular dysfunction (balance problems).

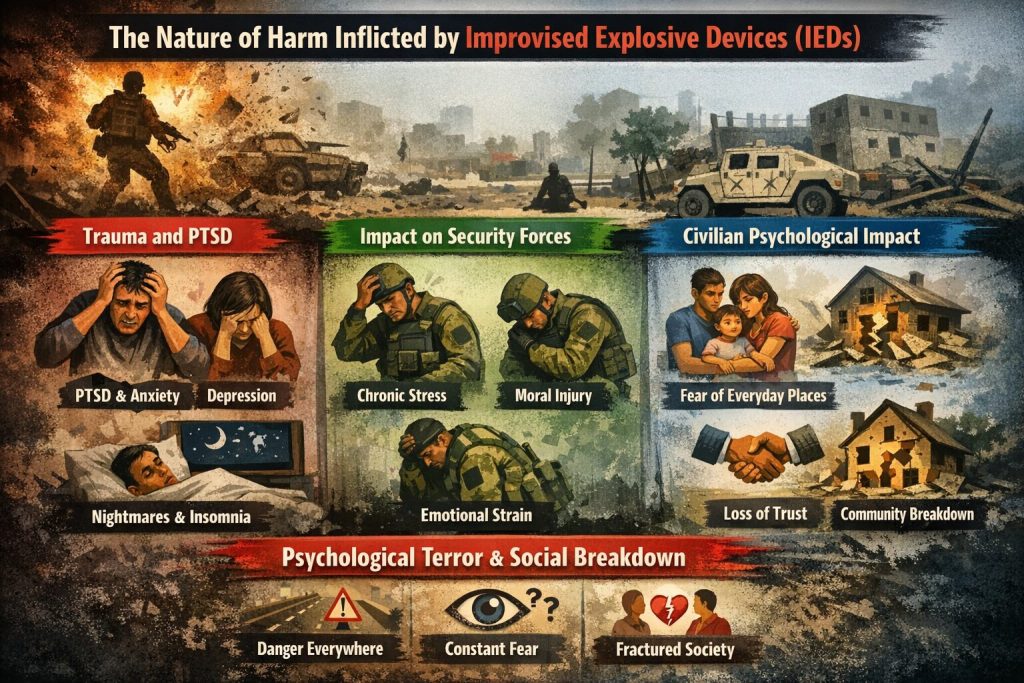

- Psychological and Mental Health Consequences

- IED attacks are unpredictable and terrifying, fostering profound trauma.

- Survivors, witnesses, and responders commonly develop PTSD, anxiety, depression, insomnia, nightmares, and hypervigilance.

- Security forces face repeated exposure, leading to moral injury, burnout, and chronic stress—even among trained counter-IED teams.

- Civilians endure widespread fear, eroding social trust, community cohesion, and daily mobility. Terror groups often exploit this psychological impact intentionally.

- Civilian and Humanitarian Impacts

IEDs’ indiscriminate placement in markets, buses, roads, schools, and places of worship disproportionately harms non-combatants—especially women, children, and the elderly.

- Permanent disabilities cause unemployment, stigma, exclusion, and intergenerational poverty.

- Fear prompts mass displacement, abandonment of farms/infrastructure, and prolonged instability.

- Economic and Infrastructural Damage

Explosions destroy roads, bridges, railways, power lines, communications, and buildings. Associated costs—emergency care, rehabilitation, victim support, counter-IED operations, and reconstruction—divert resources from development and services.

- Strategic and Institutional Effects

- Repeated IED violence erodes public confidence in government and security forces, amplifying insurgent narratives of state weakness.

- Mobility restrictions hamper humanitarian aid, economic activity, and governance, granting asymmetric advantages to non-state actors.

- Perpetrator anonymity complicates accountability under international humanitarian law.

- Environmental Consequences

Detonations contaminate soil and water with explosive residues, devastate agriculture, and leave unexploded ordnance (UXO) posing hazards for decades.

- Illustrative Examples

- Afghanistan and Iraq: IEDs accounted for approximately 50–60% of coalition fatalities, highlighting their effectiveness as a weapon of prolonged insurgency designed to offset conventional military superiority through sustained attrition and mobility denial.

- Mogadishu (14 October 2017): This large vehicle-borne IED attack in a densely populated urban area illustrates the catastrophic humanitarian impact of high-yield explosives when detonated amid civilian infrastructure and limited emergency response capacity.

- Boston Marathon (2013): The use of improvised pressure-cooker bombs at a mass public event demonstrates the vulnerability of open, civilian gatherings and the ability of low-cost IEDs to generate disproportionate casualties, fear, and global psychological impact.

- Global explosive violence (2024): The exceptionally high civilian casualty rate underscores the indiscriminate nature of IED use in populated areas, where blast effects, fragmentation, and structural collapse overwhelmingly affect non-combatants.

Conclusion

IEDs inflict far more than instantaneous destruction: they kill or maim, impose lifelong disabilities and trauma, shatter families and livelihoods, devastate communities, damage infrastructure and economies, contaminate environments, and undermine governance. In India, while LWE-affected districts have declined sharply (from 126 in 2014 to 11 in 2025, with Maoist incidents and violence falling dramatically), IEDs remain a persistent threat in residual areas.

Countering this requires a multi-pronged strategy:

- Enhanced intelligence, community engagement, and prevention to disrupt IED networks.

- Rapid trauma care, long-term rehabilitation, and mental health support for victims.

- Infrastructure restoration, economic opportunities, employment creation, and development in affected regions.

- International cooperation for accountability and peacebuilding.

Only through sustained, comprehensive efforts can societies mitigate the enduring scourge of IEDs and foster lasting security.

Thus, IED violence represents not only a tactical threat but a sustained challenge to human security and state legitimacy.