Introduction

Left-Wing Extremism (LWE), often associated with the Maoist or Naxalite movement, has long been described as one of India’s most serious internal security challenges. Originating in the 1967 peasant uprising at Naxalbari in West Bengal, the movement sought to overthrow the state through armed struggle inspired by Maoist ideology. Over subsequent decades, it expanded across parts of central and eastern India—popularly termed the “Red Corridor”—drawing strength from rural discontent, tribal alienation, and governance deficits.

Although sustained security operations and targeted development interventions have led to a sharp decline in violence and territorial influence since the mid-2010s, LWE has not disappeared. Instead, it persists in residual pockets, particularly in forested, mineral-rich, and administratively weak regions. Its continued existence today is less a reflection of revolutionary momentum than of unresolved structural grievances—relating to land, forest rights, displacement, poverty, and state credibility—that have historically underpinned the movement.

Understanding why LWE has endured despite organizational attrition and leadership losses requires a holistic examination of its historical roots, socio-economic drivers, governance failures, ideological appeal, and strategic adaptations. This analysis is essential not only to explain past persistence but also to assess the conditions necessary for preventing any future ideological or organizational resurgence.

Historical Roots of LWE

- Colonial Legacy: Unequal land distribution and exploitative agrarian systems created deep resentment among peasants.

- Post-Independence Disillusionment: Land reforms were poorly implemented, leaving marginalized communities excluded.

- Naxalbari Uprising (1967): Sparked by peasants demanding redistribution of land, it became the ideological foundation of LWE.

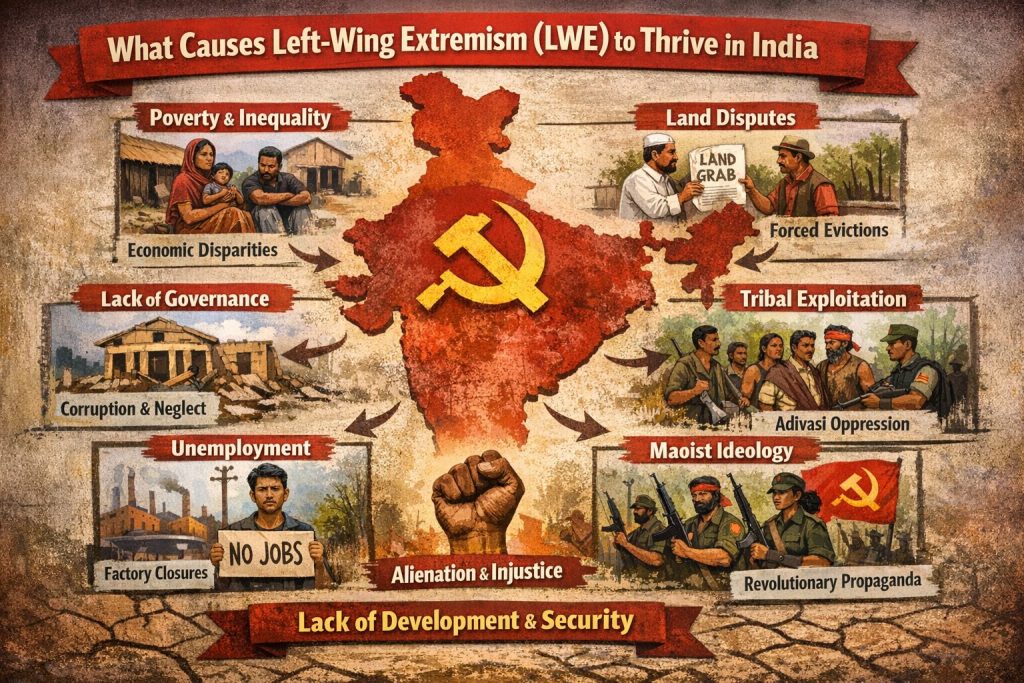

Socio-Economic Causes

- Poverty and Inequality

- Tribal and rural populations in LWE-affected areas suffer from chronic poverty, lack of healthcare, and poor education.

- Economic disparity between urban centers and tribal hinterlands fuels resentment.

- Land Alienation

- Displacement due to mining, dams, and industrial projects without adequate rehabilitation.

- Tribal communities lose traditional rights over forests and land.

- Exploitation by Middlemen

- Forest produce and agricultural goods are often bought at exploitative rates.

- Lack of access to fair markets perpetuates economic vulnerability.

Political and Governance Failures

- Weak State Presence

- Remote tribal areas often lack effective governance, infrastructure, and law enforcement.

- Maoists exploit this vacuum to establish “parallel governments.”

- Corruption and Mismanagement

- Development funds are siphoned off, leaving intended beneficiaries deprived.

- Poor delivery of welfare schemes erodes trust in the state.

- Human Rights Violations

- Heavy-handed security operations sometimes alienate local populations.

- Arbitrary arrests, custodial violence, and lack of accountability strengthen Maoist propaganda.

Cultural and Identity Factors

- Tribal Identity: Maoists position themselves as protectors of tribal rights and culture.

- Language and Alienation: Lack of representation in mainstream politics and cultural neglect deepen feelings of exclusion.

- Generational Continuity: Youth in affected areas often inherit grievances from elders, sustaining the movement.

Ideological Appeal

- Maoist ideology offers a vision of justice and equality for marginalized groups.

- Guerrilla warfare and revolutionary rhetoric attract disenfranchised youth.

- The promise of dignity and empowerment resonates with those excluded from mainstream development.

Security and Strategic Factors

- Geography: Dense forests and hilly terrain provide natural cover for insurgents.

- Guerrilla Tactics: Hit-and-run attacks, ambushes, and sabotage make them difficult to combat.

- Local Support: Maoists often win sympathy by addressing immediate grievances (e.g., land disputes, exploitation).

External and Structural Factors

- Global Influence: Inspired by Maoist movements in China and other revolutionary struggles.

- Arms and Funding: Access to illegal arms markets and extortion from contractors, businesses, and mining companies.

- Parallel Institutions: Maoists run “people’s courts” and collect taxes, creating legitimacy in certain areas.

Why Left-Wing Extremism Persists Despite Decline

The continued existence of Left-Wing Extremism today is less a function of revolutionary momentum and more a consequence of organizational survival amid unresolved structural grievances. While the movement has suffered severe leadership attrition, territorial contraction, and declining recruitment, its residual presence reflects adaptive strategies rather than ideological resurgence.

Organizational Resilience and Decentralization: Despite sustained losses, Maoist groups have retained limited operational capacity through decentralized command structures and small, locally embedded units. Fragmentation into smaller guerrilla squads has enabled rapid dispersal, concealment in remote terrain, and selective engagement, allowing survival even under sustained security pressure. This resilience has prevented total organizational collapse, even as the movement’s strategic reach has diminished substantially.

Strategic Adaptation and Tactical Retrenchment: The shift from mass mobilization and large-scale attacks toward low-intensity, localized violence marks a transition from expansion to survival. Contemporary Maoist activity is characterized by sporadic ambushes, improvised explosive devices, extortion, and symbolic actions aimed at maintaining relevance rather than controlling territory. Such tactics minimize exposure to superior state capabilities while preserving a residual insurgent footprint.

Persistence of Structural Grievances: Enduring socio-economic and governance-related grievances continue to provide ideological sustenance in select areas. Issues relating to land and forest rights, displacement from mining and infrastructure projects, uneven development outcomes, corruption, and historical mistrust of state institutions have not been uniformly resolved. In these contexts, Maoists are able to frame themselves—often with diminishing credibility—as defenders of local interests against perceived exploitation.

Passive Support and Historical Memory: In some regions, residual sympathy or passive acquiescence persists, rooted in historical experiences of neglect or coercive state interventions. Even where active support has waned, this legacy can constrain intelligence flows and slow the consolidation of state authority. Such dynamics underscore that insurgency decline does not automatically translate into social reconciliation.

From Insurgency to Latent Risk: Taken together, these factors suggest that contemporary LWE represents a latent security risk rather than an expanding insurgency. Its persistence reflects incomplete resolution of structural conditions rather than the viability of armed revolution. Consequently, while the movement’s capacity to threaten the state has been sharply curtailed, its continued survival signals the need for sustained post-conflict governance and rights-based interventions.

Case Studies

Chhattisgarh

Chhattisgarh has historically constituted the epicentre of Left-Wing Extremism due to a combination of dense forest cover, difficult terrain, and a high proportion of tribal (Adivasi) population. Regions within the Bastar division provided Maoist groups with natural concealment and logistical depth, while limited administrative reach constrained effective governance for decades. Large-scale mining and industrial projects in mineral-rich districts generated displacement and livelihood disruption, often without adequate rehabilitation, reinforcing local grievances.

These structural conditions enabled Maoists to position themselves as defenders of land, forest, and tribal autonomy, facilitating recruitment and local support. However, sustained security operations, expansion of forward-operating camps, road connectivity, and welfare penetration since the late 2010s have substantially weakened insurgent capacity. By 2025, Maoist activity in the state had been reduced to sporadic, low-intensity incidents, indicating organizational survival rather than territorial control.

Jharkhand

In Jharkhand, the persistence of LWE has been closely linked to governance deficits rather than terrain alone. Weak implementation of protective legislations—such as the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act (PESA), Chotanagpur Tenancy (CNT) Act, Santhal Parganas Tenancy (SPT) Act, and the Forest Rights Act—has enabled land alienation and resource exploitation in tribal areas. Corruption within local institutions and low tribal representation further eroded trust in the state.

These conditions allowed Maoists to exploit grievances related to land, mining, and forest access, particularly in remote rural pockets. Nevertheless, improved coordination between security forces and civil administration, coupled with targeted enforcement of land and forest laws, has reduced insurgent influence. By 2025–2026, Jharkhand recorded a sharp decline in LWE-related violence and affected districts, reflecting the impact of administrative correction alongside security pressure.

Odisha

Odisha’s experience with LWE has been shaped by tribal displacement arising from mining, infrastructure, and irrigation projects, particularly in its southern and southwestern districts. Inadequate rehabilitation and delays in recognizing forest and land rights contributed to persistent alienation among forest-dependent communities. Maoist groups capitalized on these grievances by opposing exploitative contractors and projecting themselves as intermediaries for local justice.

Over time, a combination of focused security operations, surrender policies, and improved development outreach—especially in border districts adjoining Chhattisgarh—has constrained Maoist mobility and recruitment. By the mid-2020s, the number of LWE-affected districts in Odisha had declined significantly, indicating a gradual erosion of insurgent legitimacy, even as residual grievances over displacement and livelihood security continued to require policy attention.

Analytical Takeaway

Across these cases, LWE persistence is best explained not by ideology alone, but by the interaction of geography, governance gaps, and unresolved socio-economic grievances. Variations across states underline that durable reductions in insurgency correlate with the simultaneous strengthening of security presence, rights implementation, and administrative credibility.

Government Response

- Security Operations: Deployment of paramilitary forces, specialized units, and intelligence networks.

- Development Initiatives: Infrastructure projects, welfare schemes, and rehabilitation programs.

- SAMADHAN Framework: A holistic strategy focusing on security, development, and governance.

Critical Analysis

- Security-Centric Approach: While effective in reducing violence, it risks alienating locals if not balanced with development.

- Development Deficit: Without genuine empowerment, economic projects often fail to address root causes.

- Trust Deficit: Communities often distrust state institutions due to corruption and past neglect.

Way Forward

A sustainable resolution of Left-Wing Extremism requires complementing security dominance with structural, rights-based, and governance-focused interventions. While security operations have significantly reduced violence and territorial control, long-term stability is likely to depend on the state’s capacity to address the underlying socio-economic and political conditions that historically enabled insurgent mobilization.

Inclusive and Participatory Development: Development interventions in LWE-affected areas need to move beyond infrastructure expansion toward participatory models that incorporate tribal communities into decision-making processes. Effective implementation of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act (PESA) and targeted initiatives such as Dharti Aaba Janjatiya Gram Utkarsh Abhiyan (DAJGUA) are likely to improve local ownership of development outcomes. Empirical evidence from reclaimed areas suggests that sustained delivery of basic services—roads, education, healthcare, electricity, and livelihood opportunities—correlates with reduced insurgent influence and increased community cooperation with the state.

Land and Forest Rights Implementation: Delays and inconsistencies in the implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, have historically reinforced perceptions of state neglect and exploitation. Accelerating the recognition of individual and community forest rights, ensuring transparency in claim processing, and safeguarding informed consent for development projects are likely to reduce grievance-based mobilization. Strengthening institutional mechanisms for land acquisition oversight and rehabilitation may further mitigate displacement-induced alienation in mineral-rich regions.

Strengthening Governance and Service Delivery: Persistent governance deficits—manifested through corruption, weak institutional presence, and poor welfare delivery—have been central to the endurance of LWE. Enhancing transparency in scheme implementation, improving last-mile delivery through digital monitoring, and increasing tribal representation in local administration are likely to consolidate state legitimacy. A phased transition from central force dominance to strengthened state policing, accompanied by administrative capacity-building, may help prevent governance vacuums in post-conflict areas.

Community-Oriented Policing and Trust Building: Trust between local populations and security forces remains a critical variable in post-insurgency stabilization. Adoption of rights-sensitive policing practices, localized recruitment, cultural awareness, and accountability mechanisms is likely to reduce alienation and improve intelligence flows. Evidence from forward-operating camps and civic-action initiatives indicates that sustained civil–security engagement facilitates developmental access and weakens insurgent narratives.

Rehabilitation and Reintegration Measures: Surrender and rehabilitation policies have contributed to organizational attrition within Maoist ranks. Expanding reintegration frameworks to include vocational training, psychological support, and employment linkages is likely to improve long-term outcomes for former cadres. Selective dialogue mechanisms, where feasible, may further accelerate disengagement without undermining the rule of law.

Overall, the consolidation of gains against LWE is likely to depend on the state’s ability to institutionalize governance reforms, protect rights, and ensure equitable development in formerly affected regions. Security success, while necessary, remains insufficient on its own; enduring stability is more plausibly achieved through the normalization of democratic governance and socio-economic inclusion.

Summary Table: Causes of LWE

|

Category |

Key Causes |

|

Historical |

Colonial exploitation, failed land reforms, Naxalbari uprising |

|

Socio-Economic |

Poverty, inequality, displacement, exploitation, lack of infrastructural development, unemployment |

|

Political/Governance |

Weak state presence, corruption, human rights violations |

|

Cultural/Identity |

Tribal alienation, lack of representation, generational grievances |

|

Ideological |

Maoist vision of justice, empowerment rhetoric |

|

Security/Strategic |

Geography, guerrilla tactics, local support |

|

External/Structural |

Global Maoist influence, illegal funding, parallel institutions |

Conclusion

Left-Wing Extremism in India cannot be understood solely through the lens of ideology or armed violence. Its rise and persistence have been rooted in long-standing structural deficiencies—unequal land relations, tribal alienation, displacement without adequate rehabilitation, governance deficits, and erosion of state credibility in remote regions. While Maoist ideology provided the vocabulary of rebellion, it was these material and institutional failures that enabled sustained mobilization.

Over the past decade, the Indian state has achieved substantial success in weakening the organizational and operational capacity of LWE through coordinated security operations, infrastructure expansion, welfare outreach, and surrender-cum-rehabilitation policies. The contraction of affected districts and the shift of insurgent activity into low-intensity, survival-oriented modes indicate that the movement no longer poses a systemic threat to internal security.

However, the persistence of residual pockets underscores that security-centric gains, though necessary, are insufficient for durable conflict resolution. The transition from conflict suppression to conflict closure depends on the consolidation of democratic governance, effective rights implementation, and inclusive development in formerly affected areas. Addressing historical grievances, strengthening local institutions, and restoring trust between the state and marginalized communities remain central to preventing ideological reconstitution in non-violent or latent forms.

India’s success against Left-Wing Extremism has been operationally impressive; its final victory is likely to be sociological—achieved not merely through force, but through the normalization of justice, participation, and dignity in regions long marked by exclusion.