Abstract:

The Trolley Problem remains one of the most influential moral dilemmas in philosophy, revealing the tension between utilitarianism, Kantian ethics, and real-world questions about rights, consent, and justice. From choosing whether to sacrifice one life to save many, to rejecting direct harm even for a greater good, these scenarios expose the limits of pure consequentialist thinking. Real legal examples — including R v Dudley and Stephens and key Indian cases like PUCL v. Union of India, Gian Kaur, and Aruna Shanbaug — show how courts confront similar ethical conflicts around necessity, dignity, and the value of life.

By connecting classic trolley scenarios with Indian jurisprudence, this article explores why consequences, duties, and fair procedures all matter in shaping moral judgments. Ultimately, the Trolley Problem serves as a powerful tool for understanding the complexities of ethical decision-making in law, society, and personal life.

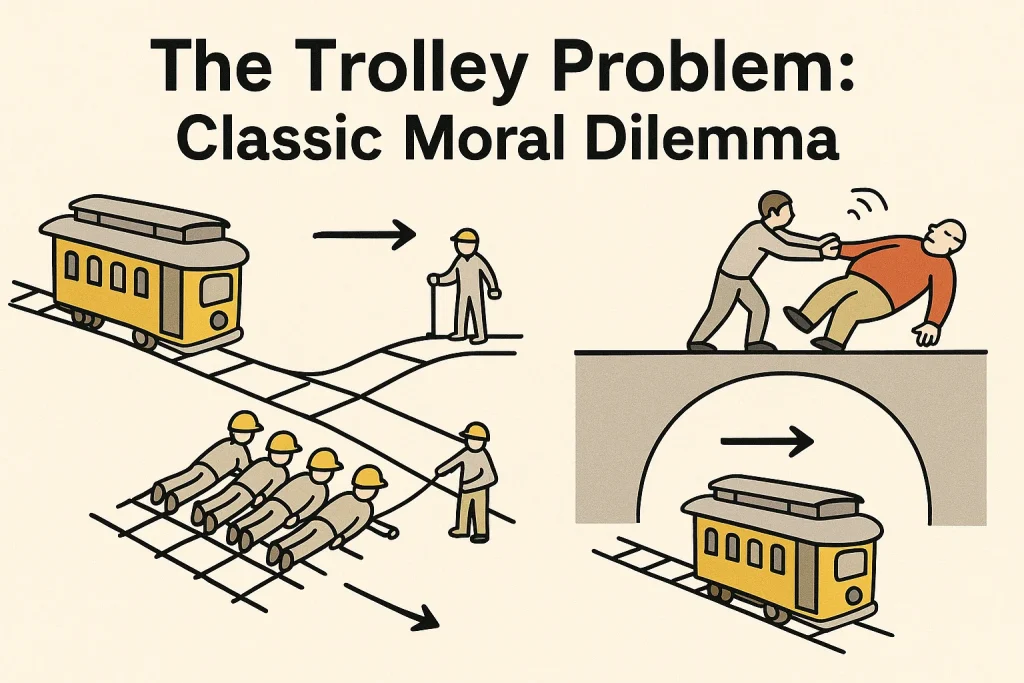

The Trolley Problem: Classic Moral Dilemma

Imagine you’re at the wheel of a runaway trolley barreling down the track. Ahead, five workers are obliviously fixing rails — if the trolley continues, they’ll die. You can’t stop the brakes, but you can steer onto a side track where a single worker is standing. Do you turn the wheel? Most people say yes: sacrifice one to save five.

Now picture another scene. You’re a bystander on a bridge. The same trolley is speeding toward five workers below, but beside you is a very large man. If you physically shove him off the bridge, he will fall in the trolley’s path and die — the five below will live. Would you push him? Most people recoil at this choice.

Variations of the Trolley Problem

Those two thought experiments — and several variations (the transplant surgeon with five dying patients and one healthy stranger, or the doctor in an emergency deciding whom to save) — expose a deep and stubborn puzzle in moral thinking.

- Switching tracks to save five

- Pushing a person to stop the trolley

- Harvesting organs from a healthy patient to save five

- Emergency room triage decisions

At first glance they invite a simple rule: do whatever produces the best overall outcome. But our intuitions refuse to be so easily corralled. Why do many of us gladly flip a switch to reroute a trolley but balk at shoving a person to their death to achieve the same numerical result?

Consequentialism And Its Limits

Why Consequences Matter — But Not Always

One influential strand of moral reasoning treats the rightness of an action as determined by its consequences. This is consequentialism; its most famous version — utilitarianism — asks us to choose the action that maximizes overall happiness or minimizes suffering.

| Key Thinker | Core Idea |

|---|---|

| Jeremy Bentham | “The greatest good for the greatest number.” |

From a strict utilitarian perspective, turning the trolley, pulling a lever, or even sacrificing one person to save many are morally justified because they produce a better overall outcome.

But our moral responses to the trolley scenarios reveal a complication. Many people make a distinction between impersonal interventions (flipping a switch) and direct interpersonal violence (pushing someone with your hands). They sense that the means — the nature of the act itself — has moral weight independent of the end. That intuition points away from pure consequentialism.

Duties And Categorical Wrongs

Some Acts Feel Categorically Wrong

Opposing consequentialist reasoning is a family of views that place moral value in duties, rights, and the intrinsic nature of actions. Think of Immanuel Kant, the eighteenth-century philosopher who argued that some acts are simply impermissible regardless of the consequences.

Under this view, killing an innocent person is inherently wrong because it violates that person’s dignity and moral status. So even if murder would save three, thirty, or three hundred, it remains forbidden.

Kantian thinking helps explain why many people find the “pushing the fat man” case repugnant: the act instrumentalizes a human being, treating them as a means to an end, not an end in themselves. That categorical prohibition isn’t blind to outcomes — it recognizes the moral costs of eroding rights, trust, and the very fabric of social life.

Real Life Complicates Theory: The Mignonette Case

These philosophical tensions aren’t merely academic. They show up in gripping real-world dilemmas — none more famous than the nineteenth-century legal case R v Dudley and Stephens. Four shipwrecked sailors, stranded in a lifeboat with almost no food or water, eventually killed and ate the cabin boy, Richard Parker, to survive.

After rescue, two of the men were tried for murder. Their defense was necessity: better one dies than the others. The public and the courts were divided — some invoked despair and survival; others insisted that the deliberate killing of an innocent person cannot be excused.

Questions Raised by the Case

- If we justify murder under extreme necessity, where do we draw the line?

- If we condemn it categorically, can we morally condemn those who had no choice but to survive?

This case forces us to confront the practical implications of our moral theories.

Indian Legal Parallels That Echo the Same Moral Tension

The dilemmas in Dudley and Stephens resonate strongly in Indian jurisprudence, where courts have grappled with similar questions about the limits of necessity, the sanctity of life, and whether extreme circumstances can ever excuse the deliberate taking of life.

PUCL v. Union of India: Encounter Killings

One striking example is PUCL v. Union of India, the landmark case on encounter killings. Police often argued that killing one suspect was necessary to save many others or to protect society.

The Supreme Court firmly rejected this utilitarian reasoning, holding that necessity cannot justify the intentional killing of a person without due process, echoing the same moral stance taken against the sailors’ justification in Dudley and Stephens.

IPC Sections 81 and 92: Limits of Necessity

| Section | Principle | Relevance to Moral Tension |

|---|---|---|

| IPC Section 81 | Acts done to prevent greater harm | Recognises necessity but not intentional killing |

| IPC Section 92 | Acts done in good faith for another’s benefit | Again excludes deliberate killing |

Together, these provisions underscore the principle that some moral and legal boundaries cannot be crossed, regardless of the consequences.

Other Cases Deepening This Moral Landscape

- Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab – The Court held that the right to life does not include the right to die, reaffirming that life has inherent value beyond calculations of suffering or utility.

- Aruna Shanbaug – Passive euthanasia was cautiously allowed, showing how the law struggles to balance compassion with the moral boundaries surrounding life and death.

- Uphaar Cinema Tragedy – Courts rejected arguments that economic or social benefit could outweigh the value of human life, mirroring the tension between utilitarian calculations and categorical moral limits.

Broader Implications

Together, these Indian cases demonstrate that the dilemmas exposed by the Mignonette tragedy are not relics of Victorian maritime law. They are alive in contemporary legal debates about policing, medical ethics, public safety, and the meaning of dignity.

R v Dudley and Stephens, viewed alongside Indian jurisprudence, shows that the philosophical debate has legal, social, and emotional consequences — and that moral reasoning must grapple with tragedy, human frailty, and communal norms.

Consent, Procedure, and Fairness

Consent, procedure, and fairness Another thread running through these dilemmas is the moral significance of consent and fair procedure. If a group agreed ahead of time to draw lots and one person loses and dies to save the others, many people feel this is less morally offensive than an ad hoc decision to kill a random innocent. Why? Because consent and impartial procedures distribute the moral burden more fairly; they respect each person as an equal participant in the outcome. But even consent raises problems: was consent truly voluntary when someone is starving, dehydrated, or otherwise vulnerable? And does the presence of a fair procedure erase the wrongness of taking a life, or only change our judgment about responsibility and legitimacy?

The Costs of Reflection — And the Danger of Skepticism

The costs of reflection — and the danger of skepticism Philosophical inquiry doesn’t just resolve puzzles; it unsettles us. Turning our familiar moral habits inside out can leave us more critical of the norms we once accepted. That’s the personal risk: self-knowledge gained through moral reflection can change how we see ourselves and the world, sometimes painfully.

Political Risk

There’s also a political risk. Deep skepticism — the idea that, because the great philosophers never finally settled these questions, we should shrug and accept moral relativism — is tempting. But shrugging off moral inquiry is itself a moral stance, and Kant warned that skepticism offers no stable home for practical reason. Even if no single answer fits all cases, avoiding the hard work of thinking about justice, rights, and consequences isn’t a neutral choice.

Why These Stories Matter

Why these stories matter The power of trolley problems, organ-transplant hypotheticals, and the Mignonette tragedy is not that they supply final answers. They are valuable because they force us to interrogate the underpinnings of our moral language:

- When do consequences trump duties?

- When do rights hold even against overwhelming utility?

- What role should consent and fair process play?

- How do we balance compassion for desperate actors with the need to uphold moral limits?

Philosophy here acts like a mirror. It makes the familiar strange, and in doing so, it teaches us to notice assumptions we previously ignored. It doesn’t promise neat closure. What it offers — if we accept the risk of discomfort — is sharper moral clarity and a readiness to live with the hard fact that some moral problems are inescapable and must be worked through, not evaded.

A Final, Practical Thought

A final, practical thought When faced with moral dilemmas in everyday life — policy debates about conscription, healthcare triage, or laws that pit individual rights against public welfare — these thought experiments are not ivory-tower games. They are tools for clearer thinking. They remind us that moral reasoning requires attention to outcomes, respect for persons, fair procedures, and the humility to admit how complex our judgments can be. Above all, they invite us to be restless about easy answers — the restlessness that, if we cultivate it, can make our moral choices more thoughtful, more humane, and, ultimately, more just.

Acknowledgement

Acknowledgement I extend my sincere gratitude to Professor Michael Sandel, whose vivid and thought-provoking teaching style brings the complexities of moral reasoning to life. Through the famous trolley dilemma and a series of escalating ethical puzzles, he challenges us to confront the contradictions in our own thinking and to recognize that questions of right and wrong seldom have simple answers. His ability to turn philosophical inquiry into an engaging, collective exploration deepens our understanding and inspires genuine reflection.