Introduction: Understanding the Complex Legal Framework of Waqf Property Ownership in India

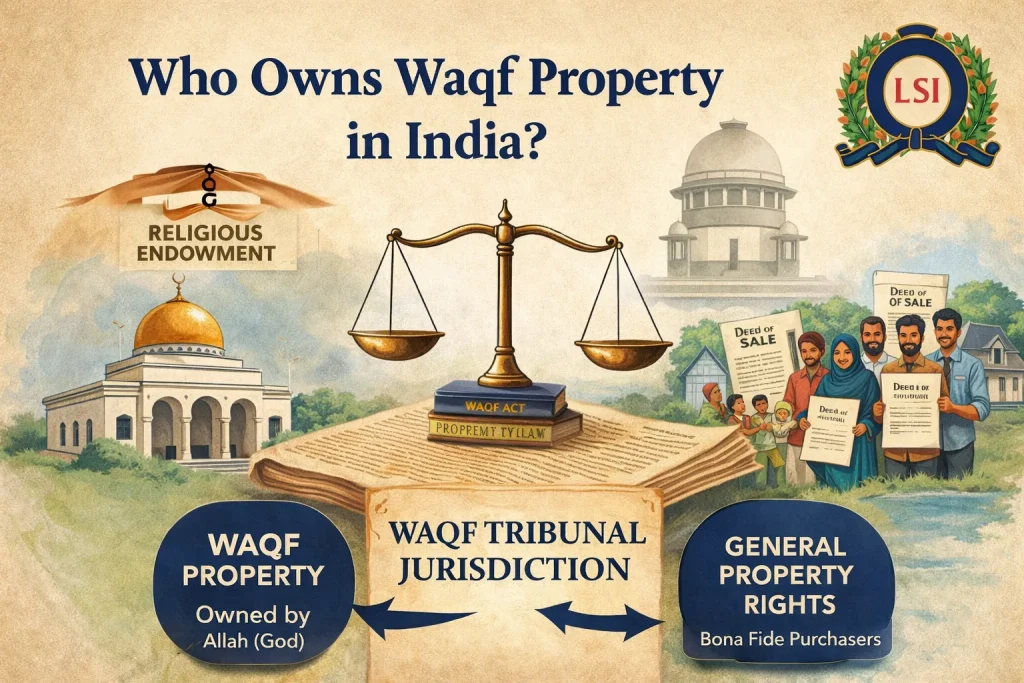

The question of “who owns Waqf property” is far more nuanced and legally intricate than it appears at first glance. Waqf, derived from the Arabic word meaning “to stop” or “to contain,” represents a permanent dedication of property for religious, pious, or charitable purposes under Islamic law. In the Indian legal context, Waqf properties occupy a unique position—they are neither purely private property nor entirely public assets, but rather constitute a distinct category of religious endowment governed by specialized legislation.

The recent Supreme Court intervention in the Munambam land dispute has brought this complex area of law into sharp focus, highlighting fundamental questions about property rights, religious endowments, jurisdictional boundaries, and the protection of bona fide purchasers. The apex court’s decision to stay the Kerala High Court’s declaration that the Munambam property is not Waqf land, while simultaneously ordering maintenance of status quo, underscores the gravity and complexity of issues involved in determining Waqf property ownership.

At the heart of the matter lies a fundamental legal principle: once property is validly dedicated as Waqf, it ceases to be the property of any individual and becomes perpetually dedicated to the purposes specified in the Waqf deed. The ownership, in legal terms, vests in Allah (God), with the beneficiaries having only usufructuary rights. The muttawalli (manager or trustee) administers the property but does not own it. This theological-legal construct creates unique challenges in modern property law, particularly when such properties are claimed decades or even centuries after their alleged dedication.

The Waqf Act, 1995 (now succeeded by the Waqf Act, 2013, with further amendments proposed) established a comprehensive framework for the administration and protection of Waqf properties in India. The Act created Waqf Boards at the state level, empowered to survey and identify Waqf properties, maintain records, and ensure proper administration. Critically, the Act also established Waqf Tribunals with exclusive jurisdiction to determine disputes regarding whether a property constitutes Waqf and related matters.

This jurisdictional exclusivity forms the crux of the current legal controversy. When the Kerala High Court proceeded to declare definitively that the Munambam property was not Waqf property, it potentially encroached upon the domain reserved exclusively for the Waqf Tribunal under Sections 83, 85, and 7 of the Waqf Act. The Supreme Court’s intervention suggests that this jurisdictional transgression cannot be overlooked, regardless of the merits of the underlying property claim.

The Munambam case also highlights the tension between protecting religious endowments and safeguarding the rights of innocent purchasers who have settled on disputed land, often for generations. Hundreds of families, predominantly fishermen, have built homes and lives on this land, claiming to be bona fide purchasers with valid title documents. Their predicament raises profound questions about the balance between historical religious claims and contemporary property rights, between the sanctity of Waqf dedications and the principle of settled possession.

Furthermore, the case illuminates the procedural complexities that arise when multiple forums—civil courts, Waqf Tribunals, and Commissions of Inquiry—attempt to address overlapping aspects of the same dispute. The Kerala Government’s constitution of an Inquiry Commission under the Commissions of Inquiry Act, 1952, to investigate the Munambam property issue, and the subsequent judicial challenge to this commission, demonstrate how Waqf disputes can spawn multiple parallel proceedings, each with different mandates and powers.

The Supreme Court’s observation that “the State Government should have challenged this order” is particularly significant. It suggests that when courts make declarations that potentially affect public interest and involve questions of specialized jurisdiction, the State has a responsibility to ensure proper appellate review, especially when such declarations might set problematic precedents or undermine the statutory framework established by Parliament.

This case arrives at a time when Waqf law in India is undergoing significant scrutiny and proposed reforms. The Waqf (Amendment) Bill has been the subject of intense debate, with discussions centered on transparency, accountability, protection of Waqf properties from encroachment, and safeguards against arbitrary declarations of property as Waqf. The Munambam dispute exemplifies precisely the concerns that have motivated these reform discussions—the need for clear procedures, definitive jurisdiction, and protection of all stakeholders’ rights.

Case Background: The Munambam Land Dispute and Its Journey Through the Courts

The Munambam land dispute represents a complex confluence of historical property transactions, religious endowment claims, administrative actions, and the rights of settled residents that has evolved over several decades before culminating in the current Supreme Court proceedings. Understanding the factual matrix and procedural history is essential to appreciating the legal questions at stake.

The property in question is situated in Vadakkekara village, Kozhikode District, Kerala, and comprises land on which hundreds of families, predominantly from the fishing community, have established their homes and livelihoods. These residents claim to be bona fide purchasers who acquired their parcels through legitimate transactions, with many families having resided on the land for two to three decades or more. Their claim to the property is based on purchase deeds and continuous, peaceful possession, creating what they believe to be indefeasible title.

The origins of the current controversy trace back to 1950, when a deed was executed concerning the property. According to the residents and their legal representatives, this original transaction did not involve any Waqf dedication. The property subsequently changed hands through various transactions over the decades, eventually being subdivided and sold to numerous individual purchasers who developed the land for residential purposes.

However, in 2019—nearly seven decades after the original 1950 deed—the Kerala Waqf Board (KWB) declared the property as Waqf property. This declaration was based on the Board’s position that the property had been validly dedicated as Waqf, specifically as a gift to the Farooq College Management Committee for religious and educational purposes. The KWB’s action was taken pursuant to its powers under the Waqf Act to survey, identify, and notify properties as Waqf.

This 2019 declaration by the KWB immediately triggered legal disputes and large-scale protests by the local inhabitants. The residents, who had invested their life savings in purchasing and developing their homes, suddenly found their property rights challenged by a religious endowment claim. The social and economic implications were profound—families faced the prospect of losing their homes, their investments, and their sense of security.

The controversy attracted significant public attention and political interest, given the large number of affected families and the broader implications for property rights in Kerala. In response to the growing dispute and public concern, the State Government of Kerala took the step of constituting an Inquiry Commission under the provisions of the Commissions of Inquiry Act, 1952 (COI Act). A notification was issued in 2024, establishing this Commission headed by a former Judge of the Kerala High Court, with a mandate to inquire into various issues relating to the Munambam property, including presumably the validity of the Waqf claim and the rights of the current occupants.

This governmental action, however, became the subject of legal challenge. Kerala Waqf Samrakshana Vedhi (Registered), an organization dedicated to the protection of Waqf properties, filed a writ petition before the Kerala High Court challenging the 2024 notification constituting the Inquiry Commission. The petitioner’s primary contention was jurisdictional: that since the property had been declared as Waqf property by the Kerala Waqf Board, any inquiry or determination regarding the nature of the property fell exclusively within the jurisdiction of the Waqf Tribunal as provided under Sections 83, 85, and 7 of the Waqf Act, 1995.

The petitioner argued that the State Government had acted ultra vires—beyond its legal powers—in constituting the Inquiry Commission to examine matters that were statutorily reserved for adjudication by the specialized Waqf Tribunal. According to this argument, the COI Act could not be invoked to circumvent or override the exclusive jurisdiction conferred upon the Waqf Tribunal by the Waqf Act, which is a special legislation dealing specifically with Waqf matters.

The Single Judge of the Kerala High Court accepted this jurisdictional argument and quashed the 2024 notification constituting the Inquiry Commission. The Single Bench held that since the subject property had been declared as Waqf property by the Kerala Waqf Board, the Inquiry Commission could not be constituted to carry out any inquiry touching upon the nature of the said Waqf property. The court found that the State Government had acted contrary to the provisions of the Waqf Act and beyond the scope of powers available under the COI Act.

This judgment by the Single Bench was then challenged by the State of Kerala through a batch of Writ Appeals before a Division Bench of the Kerala High Court. The State presumably argued that it had legitimate reasons and authority to constitute the Inquiry Commission, given the widespread public concern, the large number of affected residents, and the need for a comprehensive investigation into the competing claims.

However, the Division Bench of the Kerala High Court, in the impugned judgment now before the Supreme Court, went significantly beyond the limited jurisdictional question that was before it. While hearing the State’s appeal against the Single Judge’s order quashing the Inquiry Commission, the Division Bench proceeded to examine the substantive question of whether the Munambam property was indeed Waqf property. After examining the Waqf deed and related documents, the Division Bench made a definitive declaration that the property in question was not Waqf property but rather a gift, and therefore not subject to the Waqf Act.

This declaration by the Division Bench had far-reaching implications. It effectively resolved the fundamental dispute in favor of the current residents and against the Waqf Board’s claim, but it did so in proceedings that were ostensibly about the validity of the Inquiry Commission, not about the substantive determination of Waqf status. Moreover, it made this determination despite the existence of pending proceedings before the Waqf Tribunal challenging the very notification by which the property had been declared as Waqf.

The Division Bench’s judgment included strong observations about the potential for abuse in Waqf property declarations. The court remarked that if judicial approval were placed on arbitrary declarations of Waqf, “tomorrow any random building or structure, including Taj Mahal, Red Fort, Niyama Sabha Mandiram (State Legislature Complex), or even this Court’s building would be vulnerable of being painted with the brush of a waqf property by the Waqf Board on the basis of any random document at any point of time.” This observation reflected the court’s concern about protecting property rights from potentially unfounded Waqf claims.

Aggrieved by this sweeping declaration by the Division Bench, Kerala Waqf Samrakshana Vedhi filed a Special Leave Petition before the Supreme Court of India. The petitioner’s case before the apex court centered on the argument that the Division Bench had exceeded its jurisdiction by making a definitive determination on whether the property was Waqf, when this question fell exclusively within the domain of the Waqf Tribunal and was already the subject of pending proceedings before that forum.

The matter came before a bench comprising Justice Manoj Misra and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan. Senior Advocate Huzefa Ahmadi appeared for the petitioner, Senior Advocate Jaideep Gupta represented the State of Kerala, and Senior Advocates V Chitambaresh and Maninder Singh appeared for the residents of the land. The Supreme Court proceedings revealed the complexity of the jurisdictional and substantive issues involved, with the bench expressing concern about the High Court’s approach of going “much beyond” what was required to decide the appeal before it.

Court’s Observations: Supreme Court’s Analysis and the Jurisdictional Question

The Supreme Court’s hearing in the Munambam Waqf property case revealed critical insights into the jurisdictional complexities surrounding Waqf disputes and the appropriate role of different forums in resolving such controversies. The bench comprising Justice Manoj Misra and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan demonstrated acute awareness of the procedural irregularities in the High Court’s approach and the potential implications of allowing such jurisdictional transgressions to stand.

Senior Advocate Huzefa Ahmadi, appearing for the petitioner Kerala Waqf Samrakshana Vedhi, presented a focused jurisdictional argument. He explained to the court that his original challenge before the Single Judge was specifically directed at the Inquiry Commission constituted by the State Government. His contention was straightforward: by virtue of the statutory bar enacted under Sections 85, 83 read with Section 7 of the Waqf Act, only the Waqf Tribunal possesses jurisdiction to determine whether a property constitutes Waqf. Therefore, the State Government could not invoke the Commissions of Inquiry Act to establish a commission that would effectively adjudicate this jurisdictional question reserved for the Waqf Tribunal.

Ahmadi emphasized that the jurisdictional issue remained properly within the Waqf Tribunal’s domain, where proceedings were already pending to challenge the notification declaring the property as Waqf. However, he pointed out the problematic expansion of scope by the Division Bench: “Now, what the division bench does, it goes into my waqf deed, declares once and for all that it is not a waqf but a gift…” This observation highlighted how the High Court had transformed a limited jurisdictional challenge into a comprehensive substantive determination.

Justice Misra’s response to this submission was telling: “So you have been placed in a situation worse than before…” This remark encapsulated the paradox facing the petitioner. By successfully challenging the Inquiry Commission before the Single Judge on jurisdictional grounds, the petitioner had inadvertently opened the door for the Division Bench to make an even more adverse determination—a definitive declaration that the property was not Waqf at all, thereby potentially undermining the very foundation of the Waqf Board’s claim.

Senior Advocate Jaideep Gupta, representing the State of Kerala, raised a procedural point regarding the nature of the original petition. He submitted that the matter before the High Court was a Public Interest Litigation (PIL), not a case brought by the muttawalli (the manager of the Waqf property) claiming direct interest in the Waqf property. Gupta argued, “He claims to be a person aggrieved, but he is a person aggrieved as a public.” This submission appeared aimed at questioning the petitioner’s locus standi to challenge the Inquiry Commission and, by extension, to now appeal the Division Bench’s decision.

However, Ahmadi clarified this misconception, stating, “I don’t claim to be the PIL Petitioner…I was the writ petitioner before the Learned Single Judge, and it has categorically said that I have locus, because, if it is a Waqf Property…there is a representative interest.” This clarification was significant because it established that the petitioner was not merely a public-spirited individual but had a recognized legal interest in protecting Waqf property, which the Single Judge had already acknowledged. This representative interest is a recognized concept in Waqf law, where individuals or organizations can act to protect Waqf properties from alienation or misappropriation.

Justice Bhuyan’s observations cut to the heart of the jurisdictional problem. He questioned, “Can the writ Court go into all this?…what happens to the inquiry commission report?…He could have set aside the order of the single judge instead of going into all this. Nobody has asked for this…” These remarks reflected the bench’s concern that the Division Bench had exceeded the scope of the appeal before it. The State’s appeal was against the quashing of the Inquiry Commission; the appropriate remedy, if the Division Bench disagreed with the Single Judge, was to set aside that order and restore the Commission. Instead, the Division Bench had proceeded to adjudicate the substantive question of Waqf status, which nobody had asked it to determine in those proceedings.

This judicial overreach had significant implications. By making a definitive declaration on Waqf status, the Division Bench had potentially pre-empted the Waqf Tribunal’s exclusive jurisdiction and rendered the pending proceedings before that specialized forum redundant. It had also created a situation where a writ court, in proceedings concerning the validity of an administrative action (constitution of an inquiry commission), had made substantive determinations on property rights that required detailed examination of documentary evidence, historical transactions, and the technical requirements of Waqf law.

Justice Bhuyan’s further observation was particularly pointed: “State Government should have challenged this order…this order has made your…(referring to the petition) redundant.” This remark suggested that the Division Bench’s order was so problematic in its scope and implications that the State Government itself should have recognized the need to challenge it, regardless of whether the ultimate conclusion favored the State’s position or the residents’ claims. The observation underscored a principle of institutional responsibility—that governments must ensure proper adherence to jurisdictional boundaries and statutory frameworks, even when a particular outcome might be politically convenient or publicly popular.

Senior Advocate V Chitambaresh, representing the current residents of the land, presented the human dimension of the dispute. He submitted, “We are all bona fide purchasers of the parcels of the land…mostly fishermen, hundreds of them have erected homes…the original deed was of 1950. 69 years later they have registered the Waqf, the way the property has been assigned….” This submission highlighted the temporal aspect of the dispute—the significant gap between the original 1950 transaction and the 2019 Waqf declaration, during which numerous innocent purchasers had acquired rights in the property.

The residents’ position raised important questions about the doctrine of bona fide purchasers for value without notice, the principle of adverse possession, and the limits of Waqf Boards’ powers to declare property as Waqf decades after transactions that appear to have treated the property as alienable private property. However, Justice Bhuyan’s response—”What was the need of going into that? (regarding the impugned order)…He has gone much beyond”—indicated that while these substantive issues were important, they were not properly before the Division Bench in the form they were addressed.

The Supreme Court’s ultimate decision reflected its assessment of the jurisdictional irregularity. The bench ordered: “…The present matter requires consideration…Issue notice returnable in the week commencing 27 January. In the meantime, the declaration in the impugned judgment that the property in question is not the subject matter of ‘Waqf’ shall remain stayed. The status quo regarding the same shall be maintained.”

This order has several significant components. First, by staying the declaration that the property is not Waqf, the Supreme Court has effectively restored the position that existed before the Division Bench’s judgment—a position where the property’s Waqf status remained disputed and subject to determination by the appropriate forum. Second, by ordering maintenance of status quo, the Court has ensured that neither party can take any action to alter the ground situation while the legal issues are being resolved. Third, by issuing notice and setting the matter for further hearing, the Court has signaled that the jurisdictional and substantive issues require detailed consideration.

From a legal analysis perspective, the Supreme Court’s intervention appears to rest on several foundational principles. The first is the principle of specialized jurisdiction—when Parliament creates specialized tribunals with exclusive jurisdiction over particular categories of disputes, ordinary civil courts and writ courts cannot encroach upon that jurisdiction, except in limited circumstances such as jurisdictional error or violation of natural justice. The Waqf Act clearly establishes the Waqf Tribunal as the exclusive forum for determining whether property constitutes Waqf, and this jurisdictional allocation must be respected.

The second principle is that of judicial restraint—courts should confine themselves to deciding the issues actually before them and should not make determinations on questions that are not necessary for resolving the specific dispute at hand. The Division Bench’s decision to declare definitively that the property was not Waqf, when the appeal before it concerned only the validity of the Inquiry Commission, violated this principle of restraint.

The third principle relates to the hierarchy of remedies and forums. When a specialized statutory remedy exists (in this case, proceedings before the Waqf Tribunal), parties should ordinarily be required to exhaust that remedy before seeking relief in writ jurisdiction. The High Court’s decision to bypass the Waqf Tribunal and make its own determination disrupted this hierarchical structure.

Impact: Broader Legal and Practical Implications of the Supreme Court’s Intervention

The Supreme Court’s decision to stay the Kerala High Court’s declaration regarding the Munambam property carries profound implications that extend far beyond the immediate parties to the dispute. This intervention touches upon fundamental questions of property rights, religious endowments, jurisdictional boundaries, and the balance between historical claims and contemporary realities. The ramifications of this case will likely influence Waqf law jurisprudence, property transactions involving potentially disputed titles, and the administration of religious endowments across India.

Jurisdictional Clarity and the Role of Specialized Tribunals

Perhaps the most significant impact of the Supreme Court’s intervention is the reinforcement of jurisdictional boundaries between ordinary courts and specialized tribunals. The Waqf Act’s creation of Waqf Tribunals with exclusive jurisdiction to determine disputes regarding Waqf property reflects a legislative judgment that such matters require specialized adjudication by forums with expertise in Islamic law, Waqf administration, and the unique legal principles governing religious endowments.

By staying the High Court’s declaration and implicitly criticizing the Division Bench’s approach, the Supreme Court has sent a clear message that this jurisdictional allocation must be respected. This has important implications for the administration of justice in specialized areas of law. If ordinary civil courts or High Courts in writ jurisdiction could freely make determinations on matters reserved for specialized tribunals, the entire purpose of creating such tribunals would be defeated.

This principle extends beyond Waqf law to other areas where Parliament has created specialized adjudicatory mechanisms—consumer disputes, taxation matters, labor disputes, and various regulatory issues. The Munambam case reinforces the doctrine that specialized tribunals’ jurisdiction must be respected, and courts should not lightly assume jurisdiction over matters that fall within these tribunals’ exclusive domain.

However, this raises a related question: what is the appropriate scope of judicial review over tribunal decisions? While tribunals have exclusive jurisdiction over their subject matter, they remain subject to judicial review for jurisdictional errors, violations of natural justice, and errors of law apparent on the face of the record. The challenge is maintaining the balance between respecting tribunal autonomy and ensuring judicial oversight to prevent abuse or error. The Munambam case will likely contribute to the evolving jurisprudence on this balance.

Implications for Waqf Property Administration and Protection

For Waqf Boards across India, the Supreme Court’s intervention provides both reassurance and caution. On one hand, the stay of the High Court’s declaration that the property is not Waqf protects the Board’s authority to identify and notify Waqf properties. If High Courts could simply declare properties not to be Waqf in writ proceedings, bypassing the Waqf Tribunal, the statutory framework for Waqf protection would be severely undermined.

On the other hand, the case highlights the challenges Waqf Boards face in establishing Waqf status for properties where there has been a significant temporal gap between the alleged Waqf dedication and the Board’s notification. The 69-year gap between the 1950 deed and the 2019 Waqf declaration in the Munambam case raises legitimate questions about due diligence, the reliability of historical records, and the impact on intervening transactions.

This temporal dimension has practical implications for Waqf Boards’ survey and notification processes. Boards must ensure that their declarations of property as Waqf are based on solid documentary evidence and proper investigation, particularly when significant time has elapsed since the alleged dedication. The risk of declaring property as Waqf based on questionable historical claims is not merely legal but also social and political, as demonstrated by the large-scale protests in Munambam.

Furthermore, the case may prompt Waqf Boards to be more proactive in identifying and protecting Waqf properties before intervening rights are created. The longer a property remains unidentified as Waqf while being treated as private property in the market, the more complex the legal and equitable issues become when Waqf status is eventually asserted.

Impact on Bona Fide Purchasers and Property Transactions

From the perspective of property purchasers, the Munambam case highlights a troubling vulnerability in the Indian property market. Hundreds of families who believed they had purchased property with clear title now find themselves embroiled in a dispute over Waqf status, with their homes and investments at risk. This situation raises fundamental questions about the security of property transactions and the protection of bona fide purchasers.

The case underscores the limitations of title verification in the Indian context. Even when purchasers conduct due diligence, examine title documents, and ensure proper registration, they may remain vulnerable to claims based on historical dedications or transactions that are not reflected in contemporary records. This is particularly problematic with Waqf properties, where the dedication may have occurred decades or centuries ago, and records may be incomplete or disputed.

This vulnerability has several practical implications. First, it may increase the cost and complexity of property transactions, as purchasers and their legal advisors must conduct more extensive historical research to identify potential Waqf claims. Second, it may affect property values in areas where Waqf claims are considered possible, as the risk of future disputes creates uncertainty. Third, it may necessitate reforms in property registration and title guarantee systems to provide better protection for bona fide purchasers.

The case also raises questions about the doctrine of adverse possession in the context of Waqf property. Generally, Waqf property is considered inalienable and not subject to adverse possession. However, when numerous families have resided on property for decades, treating it as their own with the knowledge of authorities, equitable considerations come into play. The resolution of the Munambam dispute may need to address how these competing principles can be reconciled.

Implications for Government Action and Commission of Inquiry

The Supreme Court’s observations about the State Government’s role in this dispute have important implications for how governments respond to property controversies involving religious endowments. The Court’s remark that “State Government should have challenged this order” suggests that governments have a responsibility to ensure proper adherence to jurisdictional boundaries and statutory frameworks, even when a particular judicial outcome might be politically convenient.

The case also raises questions about the appropriate use of Commissions of Inquiry in property disputes. While such commissions can serve valuable purposes in investigating matters of public concern, their use becomes problematic when they are constituted to examine questions that fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of specialized tribunals. The Munambam case suggests that governments must carefully consider jurisdictional issues before constituting inquiry commissions in areas governed by special legislation.

This has broader implications for administrative action in the face of public pressure. The Munambam dispute generated significant protests and political attention, creating pressure on the State Government to take action. However, the legal challenges to the Inquiry Commission demonstrate that even well-intentioned governmental responses must respect statutory frameworks and jurisdictional boundaries. Governments must find ways to address public concerns while working within the legal architecture established by Parliament.

Social and Communal Implications

Beyond the strictly legal dimensions, the Munambam case has significant social and communal implications. Property disputes involving religious endowments have the potential to generate communal tension, particularly when they involve large numbers of people from different communities. The case involves claims by a Waqf Board (representing Muslim religious interests) over property occupied by hundreds of families (predominantly from the fishing community), creating a situation ripe for communal polarization.

The Kerala High Court’s strong observations about the potential for arbitrary Waqf declarations—including the reference to iconic structures like the Taj Mahal and Red Fort—reflect broader anxieties about the scope of Waqf Boards’ powers. While these concerns may be legitimate in some contexts, they can also contribute to communal narratives that portray Waqf law as a threat to property rights. The challenge for courts and policymakers is to address genuine concerns about arbitrary or unfounded Waqf claims while protecting the legitimate institution of Waqf and preventing communal exploitation of property disputes.

The resolution of the Munambam case will likely be watched closely by various stakeholders as an indicator of how the legal system balances these competing interests. A resolution that is perceived as fair to all parties—protecting legitimate Waqf properties while safeguarding the rights of bona fide purchasers—could serve as a model for addressing similar disputes. Conversely, a resolution perceived as one-sided could exacerbate tensions and generate further litigation.

Implications for Waqf Law Reform

The Munambam case arrives at a time when Waqf law in India is undergoing significant scrutiny and proposed reforms. The Waqf (Amendment) Bill has been the subject of intense debate, with discussions centered on transparency, accountability, protection of Waqf properties from encroachment, and safeguards against arbitrary declarations of property as Waqf. The issues highlighted by the Munambam dispute directly inform these reform discussions.

The case demonstrates the need for clearer procedures for identifying and notifying Waqf properties, with adequate safeguards for affected parties. It highlights the importance of maintaining accurate and accessible records of Waqf properties to prevent disputes. It underscores the need for effective mechanisms to resolve competing claims between Waqf Boards and other parties, including bona fide purchasers.

Any comprehensive reform of Waqf law must address these issues. This might include requirements for more rigorous investigation before property is declared as Waqf, mandatory notice to affected parties, time limitations on asserting Waqf status for properties that have been treated as private property for extended periods, and enhanced protection for bona fide purchasers. At the same time, reforms must ensure that genuine Waqf properties are protected from encroachment and alienation, and that Waqf Boards have adequate powers to fulfill their statutory mandate.

Impact on Legal Practice and Property Law

For legal practitioners, the Munambam case provides important lessons about jurisdictional strategy in Waqf disputes. The case demonstrates the risks of challenging governmental action in writ jurisdiction when doing so might open the door for courts to make broader determinations that could be adverse to one’s client. It highlights the importance of carefully framing legal challenges to avoid unintended consequences.

The case also underscores the importance of understanding the specialized nature of Waqf law and the exclusive jurisdiction of Waqf Tribunals. Lawyers advising clients on property transactions must be aware of potential Waqf issues and the limitations of ordinary civil remedies when Waqf status is disputed. Similarly, lawyers representing Waqf Boards or challenging Waqf claims must understand the proper forums and procedures for such disputes.

From a broader property law perspective, the case contributes to the ongoing tension between historical title and contemporary possession, between religious endowment claims and market transactions, and between specialized statutory regimes and general property law principles. These tensions are not unique to Waqf law but appear in various contexts, including temple properties, church lands, and government lands. The principles developed in resolving the Munambam dispute may have applicability in these other contexts as well.

FAQs: Common Questions About Waqf Property Ownership

Q1: Who legally owns Waqf property, and can it be sold or transferred?

Waqf property occupies a unique position in Indian property law. Once property is validly dedicated as Waqf, it ceases to be the property of any individual. In theological and legal terms, the ownership vests in Allah (God), with the property being perpetually dedicated to the religious, pious, or charitable purposes specified in the Waqf deed. The beneficiaries of the Waqf have only usufructuary rights—meaning they can benefit from the property’s use or income but do not own the property itself.

The muttawalli, who is the manager or trustee of the Waqf property, administers the property on behalf of the Waqf but has no ownership rights. The muttawalli’s role is fiduciary in nature—they must manage the property in accordance with the terms of the Waqf deed and for the benefit of the designated beneficiaries, but they cannot treat the property as their personal asset.

As a general principle, Waqf property is inalienable, meaning it cannot be sold, gifted, or transferred. This inalienability is fundamental to the concept of Waqf, which involves a permanent dedication of property. However, the Waqf Act does provide for limited exceptions where Waqf property can be transferred with the permission of the Waqf Board and subject to specific conditions. These exceptions typically involve situations where the transfer is necessary for the better administration of the Waqf or where the property has become useless for Waqf purposes and can be exchanged for more suitable property.

The Munambam case illustrates the complications that arise when property claimed as Waqf has been treated as alienable private property and sold to multiple purchasers over decades. If the property is ultimately determined to be Waqf, the subsequent sales would generally be void, as Waqf property cannot be validly sold without proper authorization. However, this creates significant hardship for bona fide purchasers who acquired the property in good faith, believing they were obtaining valid title. Balancing the principle of Waqf inalienability with protection for innocent purchasers remains one of the most challenging aspects of Waqf law.

Q2: What is the jurisdiction of Waqf Tribunals, and can civil courts decide Waqf disputes?

The Waqf Act establishes Waqf Tribunals with exclusive jurisdiction to determine disputes regarding whether a property constitutes Waqf and related matters. Sections 7, 83, and 85 of the Waqf Act, 1995 (and corresponding provisions in the Waqf Act, 2013) create a comprehensive statutory framework that bars the jurisdiction of civil courts over matters that fall within the Waqf Tribunal’s domain.

Section 83 of the Waqf Act, 1995 specifically provides that any dispute, question, or other matter relating to whether a property is Waqf property or not, or relating to any Waqf or Waqf property, shall be decided by the Waqf Tribunal. Section 85 contains a bar on the jurisdiction of civil courts, stating that no suit or other legal proceeding shall lie in any civil court in respect of any dispute, question, or other matter relating to any Waqf or Waqf property which is required to be determined by the Waqf Tribunal.

This exclusive jurisdiction reflects a legislative judgment that Waqf disputes require specialized adjudication by a forum with expertise in Islamic law and Waqf administration. The Waqf Tribunal is typically composed of members with knowledge of Muslim law and Waqf matters, enabling more informed decision-making on these specialized issues.

However, the jurisdiction of civil courts is not entirely ousted. Civil courts retain jurisdiction over matters that do not directly involve the determination of Waqf status. For example, if a dispute involves purely contractual issues between parties where Waqf status is not in question, civil courts may have jurisdiction. Additionally, High Courts retain their constitutional jurisdiction under Article 226 to issue writs for enforcement of fundamental rights or in cases of jurisdictional error or violation of natural justice by the Waqf Tribunal.

The Munambam case highlights the importance of respecting this jurisdictional allocation. The Supreme Court’s concern about the Kerala High Court’s Division Bench making a definitive declaration on Waqf status stems from the principle that such determinations fall within the Waqf Tribunal’s exclusive jurisdiction. While High Courts can exercise writ jurisdiction to review administrative actions or tribunal decisions, they should not bypass the Tribunal and make original determinations on matters reserved for the Tribunal’s adjudication.

Q3: What rights do bona fide purchasers have when property they bought is later claimed as Waqf?

The rights of bona fide purchasers in the face of Waqf claims present one of the most difficult and contentious issues in Waqf law. A bona fide purchaser is someone who acquires property in good faith, for valuable consideration, and without notice of any defect in the seller’s title. In ordinary property transactions, bona fide purchasers are generally protected, even if it later emerges that the seller’s title was defective.

However, Waqf property presents a special case. The principle of inalienability of Waqf property means that sales of Waqf property without proper authorization are void, not merely voidable. This creates a harsh result for bona fide purchasers: even if they had no knowledge that the property was Waqf and paid full market value, their purchase may be declared void if the property is determined to be Waqf.

This situation is particularly problematic when, as in the Munambam case, the Waqf claim is asserted many decades after the property has been treated as private property and sold to multiple purchasers. The purchasers may have conducted due diligence, examined title documents, ensured proper registration, and possessed the property openly for years, yet still find their title vulnerable to a historical Waqf claim.

The law does provide some potential protections for bona fide purchasers, though these are limited and uncertain. First, if the Waqf Board’s notification of property as Waqf is successfully challenged before the Waqf Tribunal as being without basis, the purchasers’ titles would be secure. Second, in some cases, courts have recognized equitable considerations and the need to protect innocent purchasers, particularly where there has been significant delay in asserting Waqf claims and the purchasers have made substantial improvements to the property. Third, the doctrine of estoppel may apply in limited circumstances where the Waqf Board or its representatives have acted in a manner that led purchasers to believe the property was not Waqf.

However, these protections are uncertain and case-specific. The resolution of the Munambam dispute may provide important guidance on how courts and tribunals should balance the principle of Waqf inalienability with protection for bona fide purchasers, particularly in cases involving long delays and multiple transactions. This remains an area where legal reform may be necessary to provide clearer protections while maintaining the integrity of Waqf dedications.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complex Intersection of Religious Endowment and Property Rights

The Supreme Court’s intervention in the Munambam Waqf property dispute represents a critical juncture in the evolution of Waqf law in India. By staying the Kerala High Court’s declaration that the property is not Waqf and ordering maintenance of status quo, the apex court has signaled its concern about jurisdictional overreach and the need for careful adherence to the statutory framework governing Waqf disputes. This decision has implications that extend far beyond the immediate parties, touching upon fundamental questions about property rights, religious endowments, specialized tribunals, and the protection of bona fide purchasers.

At its core, the case highlights the tension between two important legal principles. On one hand, there is the principle of Waqf inalienability—the idea that once property is validly dedicated as Waqf, it becomes perpetually dedicated to religious or charitable purposes and cannot be alienated. This principle is fundamental to the institution of Waqf and serves important purposes in protecting religious endowments from dissipation. On the other hand, there is the principle of protecting bona fide purchasers and ensuring security of property transactions, which is essential for a functioning property market and for preventing injustice to innocent parties.

The Munambam case demonstrates how these principles can come into sharp conflict, particularly when there are significant temporal gaps between alleged Waqf dedications and their assertion by Waqf Boards. The 69-year gap between the 1950 deed and the 2019 Waqf declaration, during which the property was apparently treated as private property and sold to numerous purchasers, creates a situation where strict application of Waqf inalienability principles would cause severe hardship to hundreds of families who believed they had acquired valid title.

The Supreme Court’s decision to stay the High Court’s declaration and maintain status quo suggests that the ultimate resolution of this dispute will require careful balancing of these competing interests. The Court’s observations about the High Court having gone “much beyond” what was required and the State Government’s responsibility to challenge such orders indicate that procedural regularity and respect for jurisdictional boundaries will be important factors in the final determination.

Looking forward, several potential developments merit attention. First, the Supreme Court’s final decision in this case will likely provide important guidance on the scope of High Courts’ writ jurisdiction in Waqf matters and the circumstances under which courts can make determinations that fall within the Waqf Tribunal’s exclusive jurisdiction. This will have implications for how Waqf disputes are litigated across India.

Second, the case may influence ongoing efforts to reform Waqf law. The issues highlighted by the Munambam dispute—the need for clearer procedures for identifying Waqf properties, better protection for bona fide purchasers, and mechanisms to address historical claims that emerge after significant delays—are precisely the concerns that have motivated reform discussions. The resolution of this case may inform the shape of future legislative amendments.

Third, the case may prompt Waqf Boards across India to reassess their procedures for surveying and notifying Waqf properties. The controversy generated by the Munambam notification demonstrates the risks of asserting Waqf status without thorough investigation and consideration of intervening rights. Boards may need to develop more rigorous due diligence processes and better mechanisms for engaging with affected parties before making Waqf declarations.

Fourth, the case may lead to greater awareness among property purchasers and their legal advisors about the need to investigate potential Waqf claims as part of title verification. While this may increase transaction costs, it could help prevent future disputes by identifying potential issues before purchases are completed.

Finally, the case underscores the need for a comprehensive approach to resolving long-standing property disputes involving religious endowments. Such disputes often involve not just legal questions but also social, economic, and communal dimensions. Resolution mechanisms must be capable of addressing all these dimensions while ensuring fairness to all parties.

The Munambam case serves as a reminder that property law in India operates at the intersection of multiple legal traditions, religious principles, and contemporary realities. Waqf law, in particular, must navigate the complex terrain between Islamic legal principles regarding religious endowments and modern statutory frameworks for property rights and administration. The challenge for courts, legislators, and administrators is to develop approaches that honor the religious and charitable purposes of Waqf while ensuring fairness, transparency, and protection for all affected parties.

As the matter returns to the Supreme Court for final hearing, all stakeholders—Waqf Boards, property owners, government authorities, and the broader legal community—will be watching closely. The Court’s ultimate decision has the potential to clarify important aspects of Waqf law and provide a framework for resolving similar disputes that undoubtedly exist in various parts of the country. Whatever the outcome, the case has already succeeded in focusing attention on the need for thoughtful reform and careful administration in this important but often overlooked area of Indian law.

How Claw Legaltech Can Help Navigate Waqf Property Disputes and Complex Litigation

In the complex landscape of Waqf property disputes, as exemplified by the Munambam case, legal professionals, litigants, and stakeholders require sophisticated tools to navigate the intricate web of case law, statutory provisions, and procedural requirements. Claw Legaltech offers a comprehensive suite of AI-powered legal technology solutions specifically designed to address these challenges and streamline legal research, case management, and litigation strategy.

Legal GPT: Specialized Research and Drafting for Waqf Matters

Claw Legaltech’s Legal GPT is an advanced AI-powered legal assistant that can revolutionize how lawyers approach Waqf property disputes. When dealing with complex jurisdictional questions like those in the Munambam case—involving the interplay between Waqf Tribunals, civil courts, and High Courts’ writ jurisdiction—Legal GPT can quickly provide relevant statutory provisions, case law citations, and legal principles. Lawyers can ask specific questions about Sections 83, 85, and 7 of the Waqf Act, and receive comprehensive answers with proper legal citations. The tool can also assist in drafting petitions, written submissions, and legal notices related to Waqf disputes, ensuring that all relevant legal arguments and precedents are properly incorporated. For instance, when preparing a Special Leave Petition challenging a High Court’s determination on Waqf status, Legal GPT can help identify relevant Supreme Court precedents on jurisdictional issues and draft persuasive legal arguments.

AI Case Search and Judgment Database: Comprehensive Legal Research

The Munambam case demonstrates how Waqf disputes often involve nuanced legal questions that require extensive research across multiple areas of law—property law, religious endowment law, administrative law, and civil procedure. Claw Legaltech’s AI Case Search feature, backed by a judgment database of over 100 crore rulings, enables lawyers to find relevant precedents quickly and efficiently. Instead of spending hours manually searching through case law, lawyers can use natural language queries to find judgments dealing with similar issues—such as “High Court jurisdiction in Waqf disputes,” “rights of bona fide purchasers of Waqf property,” or “bar on civil court jurisdiction under Waqf Act.” The AI-powered search understands context and can identify relevant cases even when they use different terminology, ensuring comprehensive research coverage.

Chat with Judgments: Deep Analysis of Complex Decisions

The Kerala High Court’s judgment in the Munambam case is lengthy and involves multiple legal issues. Claw Legaltech’s “Chat with Judgments” feature allows lawyers to upload such judgments and interact with them conversationally. You can ask specific questions like “What was the court’s reasoning on jurisdictional issues?” or “What precedents did the court rely on regarding Waqf inalienability?” and receive precise answers extracted from the judgment. This feature is invaluable for quickly understanding complex decisions, identifying key holdings, and extracting relevant passages for use in subsequent pleadings or arguments. For litigants and students trying to understand the implications of the Supreme Court’s stay order, this feature provides accessible insights without requiring them to parse through dense legal language.

The combination of these powerful features makes Claw Legaltech an indispensable tool for anyone involved in Waqf property disputes or similar complex litigation. Whether you’re a lawyer representing a Waqf Board, an advocate for property owners challenging Waqf claims, a government counsel navigating jurisdictional issues, or a legal researcher studying religious endowment law, Claw Legaltech provides the technological infrastructure to work more efficiently and effectively. In an area of law as specialized and evolving as Waqf property, having access to cutting-edge legal technology can make the difference between success and failure in litigation.

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. For specific legal guidance on Waqf property matters, please consult a qualified legal professional.