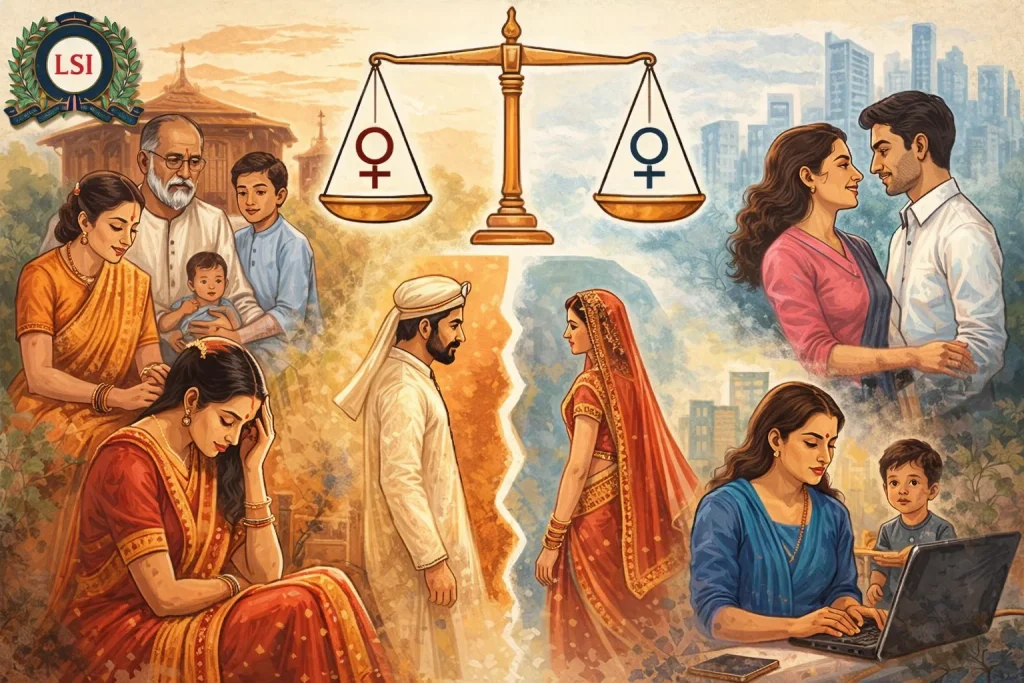

The family is the primary social institution shaping women’s lives in India. From birth to death, women’s identities, opportunities, and experiences are profoundly influenced by family structures, relationships, expectations, and norms. Indian families, while diverse across regions, religions, and classes, share certain patriarchal characteristics that systematically privilege men while subordinating women. Understanding how family and social structures shape women’s autonomy, choices, and well-being is crucial for comprehending the lived realities of Indian women and the challenges they face in asserting their rights and achieving equality.

The Indian Family: Structure and Ideology

The Indian family is not a singular entity but encompasses diverse forms—nuclear families, joint families, extended families, and increasingly, single-parent or non-traditional households. Despite this diversity, certain ideological underpinnings about family, gender roles, and women’s place within families show remarkable consistency across contexts.

The Joint Family Ideal

The joint family—multiple generations living together, sharing resources, and operating as a collective economic and social unit—has been idealized in Indian culture as the traditional, authentic family form. While the prevalence of joint families has declined with urbanization and economic changes, the ideology of the joint family continues to influence expectations and behaviors.

In the joint family ideal, hierarchy is a central aspect. Elders have authority over younger members, men over women, and within women, senior women (particularly mothers-in-law) over junior women (daughters-in-law). Individual desires and preferences are subordinated to family collective interests, as defined by family patriarchs.

For women, the joint family structure creates specific dynamics. New brides enter husbands’ joint families at the lowest status position. They’re subject to control and supervision by mothers-in-law and other senior family members. Privacy is minimal, with living arrangements, daily schedules, and even intimate relationships subject to family oversight.

The joint family can provide support—childcare assistance, economic security during crises, and social belonging. However, it also enables control over women, makes leaving abusive situations difficult, and subordinates women’s individual needs to family demands.

The Nuclear Family: Autonomy and Isolation

Nuclear families—married couples with their children living separately from extended family—have become increasingly common, particularly in urban areas. Nuclear family living can provide women more autonomy, freedom from constant supervision, and the ability to negotiate relationships with spouses directly rather than through family hierarchies.

However, nuclear families also create challenges. Women lose the support extended families sometimes provide—help with childcare, assistance during illness, or collective resources during economic hardship. The isolation of nuclear family living can leave women without allies when facing domestic violence or marital problems.

Nuclear families don’t necessarily escape patriarchal norms. Even in separate households, extended family expectations influence decisions about women’s employment, childbearing, child-rearing, and household management. Technology enables constant communication and surveillance, with mothers-in-law video-calling to supervise daughters-in-law’s activities despite physical distance.

Familial Ideology: Women as Repositories of Honor

Across family forms, certain ideological constructs consistently shape women’s experiences. Central is the notion of women as repositories of family honor (izzat). Women’s behavior—their dress, speech, mobility, relationships, and sexuality—reflects on family reputation. Protecting family honor requires controlling women’s autonomy and choices.

This ideology makes women responsible for family reputation while denying them control over their own lives. Women bear the burden of upholding honor through their conduct, yet decisions about their education, employment, marriage, and mobility are made by male family members ostensibly protecting that honor.

The honor ideology justifies extreme restrictions and violence. Women who defy family expectations—choosing their own partners, seeking divorce, pursuing unconventional careers—are seen as dishonoring families, inviting punishment. Honor killings, though officially condemned, are extreme manifestations of this ideology that views women’s autonomy as threatening family reputation.

Marriage: The Defining Transition

Marriage is the central life event for Indian women, marking the transition from natal to marital families and fundamentally reshaping their lives, identities, and social positions.

The Imperative to Marry

Marriage is not optional for most Indian women but a social and familial imperative. Unmarried women past a certain age face stigma, pity, and questions about their worth. Families feel obligated to marry daughters, viewing it as fulfilling parental duty.

This marriage imperative creates enormous pressure. Women’s education and career aspirations may be secondary to finding suitable matches. Families begin marriage preparations when daughters are quite young, with all life choices evaluated through the lens of marriageability.

The pressure to marry restricts women’s autonomy in multiple ways. Career choices may be constrained to “suitable” fields that won’t interfere with marriage prospects. Geographic mobility may be limited to avoid distance from potential marriage markets. Personal choices about appearance, behavior, and relationships are policed to maintain marriageability.

Arranged Marriage: Family Control and Women’s Agency

Arranged marriage, where families select spouses for their children, remains predominant in India. While the process has evolved—with young people sometimes having veto power or participating in selection—families, particularly parents, typically control the process.

For women, arranged marriage means limited choice in life partners. Matches are evaluated based on caste, class, education, profession, and family background, with women’s preferences about personality, compatibility, or attraction often secondary. Women meet potential husbands briefly, in artificial settings, with little opportunity to assess compatibility before making life-altering decisions.

The arranged marriage system perpetuates inequalities. Dowry, though illegal, remains integral to many arranged marriages, with grooms’ families demanding cash, goods, or property. Women’s families bear financial burdens, sometimes incurring debilitating debt. Dowry demands continue after marriage, creating ongoing vulnerability for women.

Caste endogamy—marrying within one’s caste—is enforced through arranged marriage, perpetuating caste hierarchy. Families reject matches across caste lines, sometimes violently, to maintain caste purity. Women choosing partners from different castes face family rejection, social ostracism, and sometimes honor violence.

Love Marriage: Choice and Consequences

Love marriage—individuals choosing their own partners—challenges family control and remains controversial. Young people, particularly in urban areas, increasingly seek autonomy in partner selection, but family opposition remains strong.

Women in love marriages face specific consequences. Families may disown daughters who marry against their wishes. Financial support may be withdrawn. Social networks may shun couples who married for love, particularly across caste or religious lines. Women bear a disproportionate burden of family rupture, often blamed for dishonoring families.

Inter-caste and inter-religious marriages face particular hostility. Such relationships challenge caste hierarchy and religious boundaries that families and communities police vigorously. Couples face social ostracism, economic boycott, and sometimes violence from families or community members.

Despite obstacles, love marriages are increasing, particularly among educated, urban young people. This shift represents an assertion of individual autonomy against collective control. However, the resistance love marriages face reveals how deeply family control over marriage is entrenched.

Marriage and Women’s Lives

Marriage fundamentally transforms women’s lives in ways it doesn’t transform men’s. Women typically move to their husbands’ homes and locations, disrupting education, careers, and social networks. They adopt husbands’ surnames and sometimes even first names are changed. Identity becomes defined by marital status and relationship to husbands.

Expectations for married women are rigid—prioritizing husbands and in-laws over natal families, managing households competently, bearing children (especially sons), maintaining family honor through conduct, and subordinating individual needs to family welfare.

The institution of marriage itself is gendered unequally. Divorce remains stigmatized for women far more than men. Divorced women face social judgment, economic hardship, and obstacles to remarriage, while divorced men remarry easily. Widowhood affects women’s lives dramatically—with restrictions, rituals, and loss of status—while widowers face minimal constraints.

Motherhood: Compulsory and Defining

Motherhood is constructed as women’s ultimate fulfillment and primary identity in Indian society. The cultural glorification of motherhood, while ostensibly honoring mothers, constrains women’s choices and identities.

The Pressure to Bear Children

Married women face intense pressure to conceive quickly. Questions about pregnancy begin soon after marriage, and the inability or unwillingness to conceive brings stigma and stress. Women are blamed for infertility even when male factors are responsible. Infertile women face abuse, divorce, or pressure to accept husbands’ second marriages.

The pressure continues until women produce sons. The preference for male children means women who bear only daughters face disappointment, blame, and pressure to continue childbearing until sons arrive. Sex-selective abortion, despite being illegal, persists because of this son preference.

Women’s bodies become contested terrain during pregnancy. Families control what pregnant women eat, their activities, and medical decisions. Autonomy over one’s own reproductive process is limited, with extended families and medical establishments making decisions about women’s pregnancies and deliveries.

Motherhood and Identity

Upon becoming mothers, women’s identities transform. They’re primarily known through relationships to children rather than as individuals. Women may be addressed as “so-and-so’s mother” rather than by their own names. Professional identities, personal interests, and individual aspirations may be subsumed under maternal identity.

The idealization of self-sacrificing motherhood creates impossible standards. Good mothers are expected to sacrifice personal ambitions, comfort, and needs for the welfare of their children. Women pursuing careers or personal interests are sometimes viewed as selfish or neglecting children, while fathers’ pursuit of careers is expected.

Intensive mothering norms—requiring constant attention, extensive educational involvement, and emotional labor—burden mothers while fathers remain peripheral to childcare. The unequal division of parenting work disadvantages women professionally and personally while being naturalized as maternal instinct rather than recognized as unequal labor distribution.

Child-Free Women: Stigma and Judgment

Women choosing not to have children face incomprehension and judgment. The decision to remain child-free is viewed as unnatural, selfish, or tragic. Women are assumed to be unable to conceive rather than choosing not to, and involuntary childlessness receives sympathy while voluntary childlessness receives condemnation.

Married women without children occupy ambiguous social positions. They don’t achieve the status motherhood confers, but also avoid some demands mothers face. However, social events, conversations, and relationships often center on children, leaving child-free women marginal.

The Mother-in-Law and Daughter-in-Law Dynamic

One of the most fraught relationships in Indian family life is between mothers-in-law (saas) and daughters-in-law (bahu). This relationship, shaped by patriarchal family structures, creates conflict and suffering for women while pitting them against each other.

Power Dynamics

New brides enter marital families at the lowest hierarchical position. Mothers-in-law, having endured similar subordination in their youth, now occupy positions of relative power. They supervise daughters-in-law’s work, evaluate their competence, and control their behavior.

This dynamic creates resentment and conflict. Daughters-in-law chafe under supervision and criticism. Mothers-in-law feel disrespected by daughters-in-law they view as lazy, incompetent, or disrespectful. The relationship is structurally designed for conflict, with built-in power imbalances and competing interests.

Domestic Violence by Mothers-in-Law

Mothers-in-law are frequently perpetrators of domestic violence against daughters-in-law—physical abuse, verbal abuse, emotional manipulation, and economic exploitation. This intra-gender violence reflects how patriarchal structures turn women against each other.

Dowry-related violence often involves mothers-in-law as primary perpetrators or collaborators. They make demands, harass daughters-in-law for insufficient dowries, and sometimes participate in violence, including murder. The complicity of mothers-in-law in violence against daughters-in-law reveals how patriarchy recruits women to enforce their own oppression.

Generational Changes

Contemporary dynamics show some evolution. Educated daughters-in-law may assert themselves more than previous generations. Nuclear family living separates mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law, reducing daily friction. Some mothers-in-law, recognizing the suffering they endured, consciously choose different relationships with daughters-in-law.

However, traditional expectations persist. Mothers-in-law may use technology to maintain surveillance and control from a distance. Cultural narratives continue to glorify submissive daughters-in-law and authoritative mothers-in-law, perpetuating dysfunctional dynamics.

Sisters, Brothers, and Sibling Relationships

Sibling relationships in Indian families are profoundly shaped by gender, creating different experiences and expectations for sisters and brothers.

Brother-Sister Bonds

Indian culture idealizes the brother-sister bond, celebrating it through festivals like Raksha Bandhan (where sisters tie protective threads on brothers’ wrists) and narratives of brothers protecting sisters. This idealization contains both affection and control.

Brothers are expected to protect sisters’ honor, which often means controlling their behavior, relationships, and choices. This protective ideology justifies surveillance and restrictions. Brothers may police sisters’ clothing, friendships, and mobility, positioning themselves as guardians of family honor through controlling sisters.

The protection narrative also creates expectations that brothers will support sisters in marital families, intervening if sisters face abuse. However, this support is conditional on sisters’ conformity to family expectations. Sisters who defy families—marrying against wishes or seeking divorce—may be abandoned by brothers.

Unequal Treatment

Differential treatment of sons and daughters is pervasive. Sons receive better nutrition, education, and resources. Their futures are invested in, while their daughters are viewed as temporary family members who will join other families through marriage. This unequal investment creates resentment and affects sisters’ life chances.

Brothers inherit property while sisters are often excluded or pressured to relinquish inheritance rights. After parents’ deaths, family homes and assets typically pass to sons, with sisters expected to accept token gifts rather than claim legal shares.

The preference for brothers over sisters is internalized by some women, who themselves favor sons over daughters, perpetuating cycles of discrimination. However, some women resist, insisting on equal treatment for daughters and challenging the preferential treatment of sons.

Women’s Relationships: Solidarity and Competition

Women’s relationships with other women—mothers, sisters, friends, and female relatives—are complex, containing both solidarity and competition within patriarchal structures.

Mother-Daughter Relationships

Mothers are primary socializers, teaching daughters gender norms, domestic skills, and survival strategies within the patriarchy. Mother-daughter relationships are often close, with mothers providing emotional support, practical help, and advocacy.

However, mothers also enforce patriarchal norms, restricting daughters’ autonomy, prioritizing sons, and pressuring daughters into marriages or motherhood. Mothers who suffered under patriarchy may perpetuate similar suffering for daughters, viewing it as inevitable or necessary.

Some mothers resist patriarchal norms, supporting daughters’ education, careers, and choices even against family opposition. These mothers model alternative possibilities and create space for daughters’ autonomy. The evolution of mothers’ attitudes reflects broader social changes in gender norms.

Female Friendships

Female friendships provide crucial emotional support, particularly for women facing restrictions in family contexts. Friends offer confidantes for sharing experiences, allies in navigating social expectations, and sources of joy and connection outside family obligations.

However, women are sometimes positioned as competitors for marriage prospects, social status, or male approval. Cultural narratives portray women as jealous, gossipy, and unable to maintain friendships, undermining potential solidarity.

Despite structural obstacles, many women build deep, lasting friendships that sustain them through life challenges. These friendships, though sometimes undervalued compared to family relationships, provide essential support networks.

Changing Dynamics: Urban, Educated Women

Social changes—urbanization, education, employment, exposure to diverse ideas—are transforming some women’s family experiences and expectations.

Negotiating Tradition and Modernity

Educated, urban women often navigate contradictions between traditional family expectations and contemporary aspirations. They may pursue careers while facing pressure to prioritize family. They seek egalitarian marriages while managing traditional in-law relationships. They want autonomy while valuing family connections.

This negotiation creates stress and requires constant balancing. Women develop strategies—delaying marriage to establish careers, negotiating with families about work or mobility, creating nuclear households while maintaining extended family ties, or selectively embracing and rejecting traditions.

Some women openly reject traditional expectations—choosing partners across caste or religious lines, remaining unmarried, or prioritizing careers over motherhood. These choices still face resistance but are becoming more socially acceptable in certain urban, educated contexts.

Technology and Transformation

Technology is changing family dynamics in complex ways. Women use social media to connect beyond family surveillance, access information about rights and opportunities, and build support networks. Dating apps enable meeting potential partners outside family networks.

However, technology also enables new forms of control. Families use location tracking, social media monitoring, and constant communication to surveil women. Technology-facilitated harassment and image-based abuse affect women who transgress family expectations.

Regional and Cultural Variations

Family structures, gender norms, and women’s experiences vary significantly across India’s diverse regions, religions, and communities.

Regional Differences

Northern Indian families often exhibit more restrictive norms—purdah practices, limited female mobility, strong son preference, and rigid gender roles. Southern regions sometimes show relatively more egalitarian practices, though patriarchy persists across the country.

North-eastern states and some tribal communities have matrilineal traditions where property and lineage pass through women. These communities offer different family experiences for women, though modernization and integration with mainland Indian culture are eroding some traditional practices.

Religious Variations

Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, and other religious communities have specific family practices and norms. While patriarchy cuts across religions, its specific manifestations vary—purdah practices among some Muslim communities, joint family structures more common among Hindus, or specific marriage and inheritance customs in different religious traditions.

However, religious differences in women’s family experiences shouldn’t be overstated. Across religious communities, women face similar fundamental constraints—male authority, control over sexuality and reproduction, restrictions on autonomy, and expectations of self-sacrifice for family welfare.

The Impact on Women’s Autonomy and Well-being

Family structures and social expectations profoundly affect women’s autonomy, mental health, and overall well-being.

Restricted Autonomy

Family control over women’s education, employment, mobility, finances, and life choices restricts autonomy at every stage. Women’s preferences about careers, where to live, how to spend money, or even daily schedules may be overridden by family decisions.

The restriction of autonomy affects psychological well-being. Lack of control over one’s life correlates with depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem. Women who cannot pursue aspirations or make basic life decisions experience frustration and helplessness.

Mental Health Impacts

Family pressures contribute significantly to women’s mental health problems. The stress of meeting impossible standards—being perfect wives, mothers, and daughters-in-law—creates a psychological burden. Unsupportive or abusive family relationships cause trauma and distress.

However, mental health problems are stigmatized, and women’s emotional struggles are dismissed as weakness or attention-seeking. Families may prevent women from seeking mental health care, viewing it as shameful or unnecessary.

Economic Dependence

Family structures often ensure women’s economic dependence on male relatives. Limited employment, unequal inheritance, lack of asset ownership, and male control over finances keep women dependent, making it difficult to leave abusive situations or assert autonomy.

Economic dependence particularly affects divorced, widowed, or unmarried women who cannot rely on husbands. Without independent resources, these women depend on their families, who may be unwilling or unable to support them.

Pathways to Change

Transforming family structures and social norms to support women’s autonomy and equality requires multi-level interventions.

Legal Reforms and Enforcement

Laws ensuring women’s property rights, protecting against domestic violence, prohibiting dowry, and guaranteeing equal inheritance must be rigorously enforced. Legal awareness programs can help women know and claim their rights.

Personal law reforms ensuring gender equality in marriage, divorce, inheritance, and maintenance across religious communities would eliminate legal discrimination. However, such reforms require navigating religious sensitivities and political calculations.

Economic Empowerment

Women’s economic independence through employment, entrepreneurship, and asset ownership provides resources to negotiate family relationships from positions of strength rather than dependence. Policies supporting women’s economic participation—childcare, equal pay, and non-discrimination—facilitate independence.

Education and Awareness

Education that includes gender equality curricula, critical thinking about social norms, and awareness of rights empowers women to question and challenge restrictive family expectations. Comprehensive sexuality education provides knowledge about relationships, consent, and autonomy.

Public awareness campaigns challenging harmful norms—son preference, dowry, honor ideology—can shift attitudes. Media portrayal of diverse family forms and egalitarian relationships normalizes alternatives to traditional patriarchal structures.

Men’s Engagement

Transforming family dynamics requires engaging men—as sons, brothers, husbands, and fathers—in questioning patriarchal privileges and adopting egalitarian practices. Men who share household work, respect women’s autonomy, and challenge family restrictions on women create more equitable family environments.

Supporting Alternative Family Forms

Recognizing and supporting diverse family forms—single-parent families, child-free couples, unmarried individuals, LGBTQ+ families—challenges the primacy of heterosexual, married-with-children nuclear or joint families. Legal recognition and social acceptance of diverse family forms expand women’s choices.

Conclusion

Family and society are the primary contexts shaping Indian women’s lives, profoundly influencing their opportunities, choices, and experiences. Indian family structures, despite regional and religious variations, share patriarchal characteristics that systematically privilege men while subordinating women to family collective interests as defined by male authority.

From birth through marriage, motherhood, and old age, women navigate family expectations that restrict autonomy, control sexuality and reproduction, limit economic independence, and subordinate individual needs to family welfare. The ideology of family honor places the burden of family reputation on women’s behavior while denying them control over their lives.

Yet families are not monolithically oppressive. They provide love, support, belonging, and resources. Many women value family connections and find fulfillment in family relationships. The challenge is transforming families from patriarchal institutions that subordinate women to supportive structures that nurture all members’ autonomy and well-being.

Change is occurring—educated urban women increasingly assert autonomy, love marriages challenge family control, and some families embrace egalitarian practices. However, transformation is uneven and faces resistance from those invested in traditional hierarchies.

Achieving genuine equality for Indian women requires transforming both family structures and the broader social norms that shape family expectations. When women can pursue education and careers without family obstruction, choose partners without family control, decide about childbearing freely, maintain autonomy within marriages, and access economic resources independently, Indian families will support rather than constrain women’s flourishing. Until then, the family—ostensibly the source of love and security—remains for many women a primary site of oppression and control.