Introduction

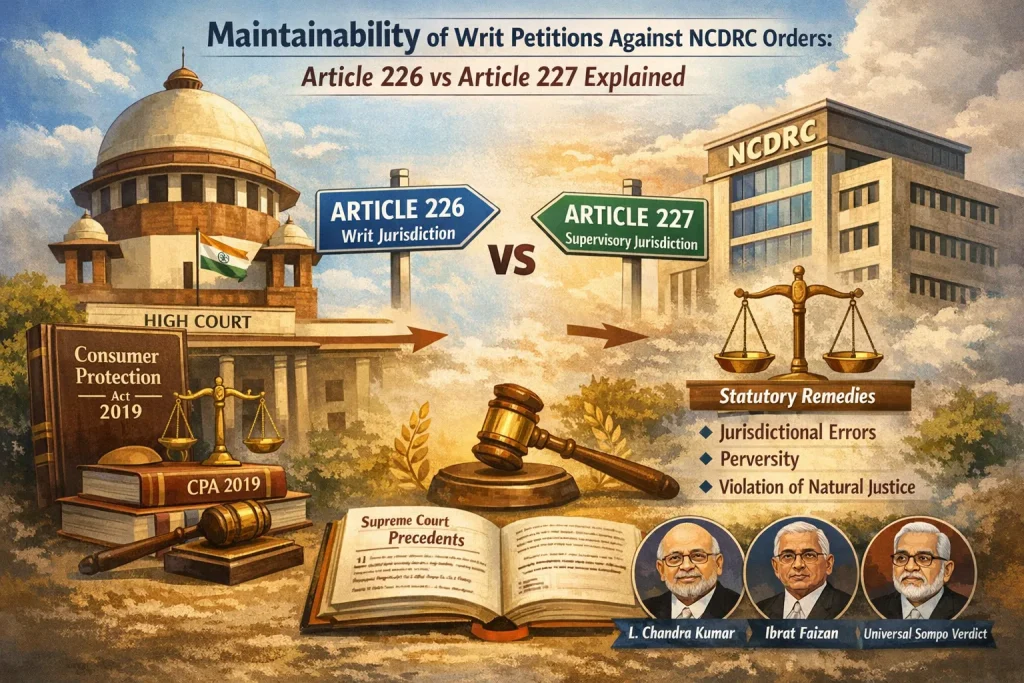

Writ petitions under Article 226 of the Constitution challenging orders of the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC) are technically maintainable, as the NCDRC qualifies as a “tribunal” amenable to High Court jurisdiction per the seminal Constitution Bench decision in L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997) 3 SCC 261.

Maintainability and Judicial Restraint

However, such petitions should not be normally entertained, with High Courts prioritizing the supervisory jurisdiction under Article 227 where available.

Exhaustion of Statutory Remedies Under the CPA, 2019

This restraint ensures the exhaustion of statutory remedies under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019 (CPA), reserving Article 226 intervention for exceptional cases involving jurisdictional errors, perversity, or violations of natural justice.

Role of the NCDRC and the Appellate Structure

The NCDRC’s dual role—original and appellate—further underscores this hierarchy, with no direct appeal to the Supreme Court under Section 67 for appellate orders, directing parties to jurisdictional High Courts first.

Exceptional Circumstances Justifying Article 226 Intervention

- Jurisdictional errors

- Perversity

- Violations of natural justice

Key Judicial Principles

1. L. Chandra Kumar: The Foundational Framework

The foundational principle stems from L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997) 3 SCC 261, where a Constitution Bench affirmed that tribunals like the NCDRC are subject to judicial review under Articles 226 and 227, but such review must not supplant statutory mechanisms. The Court held:

“We hold that all decisions of Tribunals, whether created pursuant to Article 323-A or Article 323-B of the Constitution, will be subject to the High Court’s writ jurisdiction under Articles 226/227 of the Constitution, before a Division Bench of the High Court within whose territorial jurisdiction the particular Tribunal falls.” (Para 91)

Critically, the Court declared that “the power of judicial review under Articles 226 and 227 is a basic feature of the Constitution and cannot be ousted,” thereby striking down provisions that sought to completely exclude High Court jurisdiction. However, this did not mean writs should be routinely entertained. The Court clarified that tribunals serve as “supplemental, not substitute” mechanisms, filtering frivolous claims before reaching higher courts.

2. Cicily Kallarackal: Caution Against Bypassing Statutory Appeals

This principle was reinforced in Cicily Kallarackal v. Vehicle Factory (2012) 8 SCC 524, where the Supreme Court held:

“Despite this, we cannot help but state in absolute terms that it is not appropriate for the High Courts to entertain writ petitions under Article 226 of the Constitution of India against the orders passed by the Commission, as a statutory appeal is provided and lies to this Court under the provisions of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986.” (Para 4)

The Court issued a “direction of caution” that entertaining writs where statutory appeals exist would undermine the Act’s expeditious framework. This judgment clarifies that writs under Article 226 are not maintainable against orders appealable to higher consumer fora, as it would frustrate legislative intent.

3. Ibrat Faizan: Article 227 as the Proper Remedy

In Ibrat Faizan v. Omaxe Buildhome Pvt. Ltd. (2022) 8 SCC 502, the Supreme Court clarified that NCDRC appellate orders under Section 58(1)(a)(iii) are challengeable via Article 227 before jurisdictional High Courts, not direct Supreme Court appeals under Article 136. The Court held thus:

“Now so far as the remedy which may be available under Article 136 of the Constitution of India is concerned, it cannot be disputed that the remedy by way of an appeal by special leave under Article 136 of the Constitution of India may be too expensive and as observed and held by this Court in the case of L. Chandra Kumar (supra), the said remedy can be said to be inaccessible for it to be real and effective. Therefore, when the remedy under Article 227 of the Constitution of India before the concerned High Court is provided, in that case, it would be in furtherance of the right of access to justice of the aggrieved party… to approach the concerned High Court at a lower cost.” (Para 13)

The Court upheld the CPA’s hierarchy, directing parties to High Courts first and affirming NCDRC’s “tribunal” status for limited supervisory review, while cautioning against using Article 136 to circumvent this framework.

4. Universal Sompo: Territorial Jurisdiction Clarified

More recently, in Universal Sompo General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Suresh Chand Jain (2023) SCC OnLine SC 877, the Supreme Court clarified territorial jurisdiction, holding:

“In the aforesaid view of the matter, we have reached to the conclusion that we should not adjudicate this petition on merits. The petitioner would be at liberty to approach the jurisdictional High Court either by way of a writ application under Article 226 of the Constitution or by invoking the supervisory jurisdiction of the jurisdictional High Court under Article 227 of the Constitution.” (Para 38)

The Court emphasized that aggrieved parties must approach the “jurisdictional High Court” under Articles 226 or 227 for NCDRC appellate orders, emphasizing territorial jurisdiction based on the situs of the original cause of action rather than the NCDRC’s location in Delhi. This prevents forum-shopping and aligns with principles of access to justice.

5. Siddhartha S. Mookerjee: Cause of Action Determines Jurisdiction

This was further clarified in Siddhartha S. Mookerjee v. Madhab Chand Mitter (2024) 3 SCC 1, which reiterated that the “concerned High Court” is determined by where the dispute originated, not the appellate forum. The Supreme Court observed:

“The respondent No.1 ought to have approached the High Court of Calcutta being aggrieved by the impugned judgment as the entire cause of action in the present case has arisen in Kolkata… Merely, because the NCDRC has allowed the revision petitions filed by the appellants and the respondent no.2 would not be a ground to vest jurisdiction in the High Court of Delhi.” (Para 9)

This judgment definitively establishes that “cause of action is bundle of facts existing at the stage of pre-institution of any case” and the mere fact that NCDRC (located in Delhi) passed an order does not confer jurisdiction on Delhi High Court.

6. Article 227 vs. Article 226: Scope and Application

Article 227’s supervisory scope is narrower than Article 226’s broader writ powers, limited to correcting jurisdictional excesses or patent errors, not re-appreciating evidence. In Shalini Shyam Shetty v. Rajendra Shankar Patil (2010) 8 SCC 329, the Supreme Court held:

“Supervisory jurisdiction under Article 227 of the Constitution is exercised for keeping the subordinate courts within the bounds of their jurisdiction. When a subordinate Court has assumed a jurisdiction which it does not have or has failed to exercise a jurisdiction which it does have or the jurisdiction though available is being exercised by the Court in a manner not permitted by law and failure of justice or grave injustice has occasioned thereby, the High Court may step in to exercise its supervisory jurisdiction.”

This principle was followed in Ibrat Faizan v. Omaxe Buildhome Pvt. Ltd. (2022) 8 SCC 502, reaffirming that Article 227 does not permit evidence re-appreciation. Thus, while Article 226 offers discretionary relief for fundamental rights enforcement, it yields to Article 227’s superintendence over tribunals to maintain judicial discipline.

Summary of Key Judicial Principles

| Case | Core Principle |

|---|---|

| L. Chandra Kumar (1997) | Judicial review under Articles 226/227 is a basic feature; tribunals are supplemental, not substitutes |

| Cicily Kallarackal (2012) | Writ petitions should not bypass statutory appellate remedies |

| Ibrat Faizan (2022) | Article 227 is the appropriate remedy against NCDRC appellate orders |

| Universal Sompo (2023) | Territorial jurisdiction lies with the High Court of the cause of action |

| Siddhartha S. Mookerjee (2024) | NCDRC’s location does not confer jurisdiction; cause of action governs |

Key Judicial Precedents

1. Allahabad High Court in M/s Sahu Land Developers Pvt. Ltd. v. State of UP (2025:AHC:LKO:79436-DB)

Dismissing a writ under Article 226 against an NCDRC appellate order directing plot refunds, the Division Bench of Justices Shekhar B. Saraf and Prashant Kumar held:

“When a supervisory jurisdiction under Article 227 is available to the petitioner, writ petition under Article 226 should not be normally entertained but the remedy under Article 227 is always available to the petitioner.”

The Court emphasized that mere dissatisfaction with concurrent findings does not justify bypassing Article 227. Article 226 applies only for:

- Grave injustice

- Violations of principles of natural justice

- Breaches of fundamental rights

- Patent illegality

None of these were pleaded in the case, reinforcing the rule of alternate remedy. The Court refused to allow re-examination of factual disputes like possession knowledge, deeming them unsuitable for writ proceedings.

The Court observed thus:

“Writ under Article 226 serves as an extraordinary corrective remedy, not an appellate forum or substitute for statutory hierarchies. Mere dissatisfaction with concurrent findings does not qualify as exceptional; Article 227 suffices for jurisdictional errors.”

2. Delhi High Court in Punjab National Bank v. Rohit Malhotra (2024) SCC OnLine Del 7035

In a batch of matters involving NCDRC orders from non-Delhi State Commissions, the Court ruled:

“The words ‘jurisdictional High Court’ as used in Universal Sompo General Insurance Co. Ltd (supra) cannot be automatically inferred to be Delhi High Court only… such phrases ‘concerned High Court’ and ‘Jurisdictional High Court’ would not ipso facto mean ‘Delhi High Court’, more particularly, in view of Siddhartha S. Mookerjee.”

The Court held that:

- NCDRC appellate orders arising from non-Delhi State Commissions cannot be challenged under Article 227 in the Delhi High Court solely due to the NCDRC’s location.

- Such challenges must be filed before the High Court having jurisdiction over the original forum.

This interpretation aligns with Universal Sompo and prevents overburdening the Delhi High Court, thereby promoting true access to justice. The Court further observed that the cause of action is a “bundle of facts existing at the stage of pre-institution” and that passing of orders by superior courts does not create a fresh cause of action.

3. Bombay High Court in Aparna Abhitabh Chatterjee v. Union of India (2022) SCC OnLine Bom 760

While upholding writ maintainability against NCDRC execution orders, the Court stressed that invocation of Article 226 must remain exceptional. It dismissed routine challenges in order to avoid diluting Section 71’s deeming provision, which equates NCDRC orders to civil decrees.

The Court emphasized that:

- Execution proceedings require adherence to specific procedural safeguards.

- Writ petitions should not be used as a routine mechanism to challenge execution proceedings.

- Jurisdictional error must be clearly demonstrated for Article 226 intervention.

Comparative Summary of Judicial Reasoning

| High Court | Case | Core Holding | Article Applied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allahabad High Court | M/s Sahu Land Developers Pvt. Ltd. | Article 226 not maintainable where Article 227 remedy exists | Article 227 preferred |

| Delhi High Court | Punjab National Bank v. Rohit Malhotra | Jurisdiction lies with High Court of original forum, not NCDRC location | Article 227 jurisdiction clarified |

| Bombay High Court | Aparna Abhitabh Chatterjee | Writs against execution orders only in exceptional cases | Article 226 (exceptional use) |

Arguments Against Normal Entertainment of Article 226 Petitions

High Courts must exercise Article 226 cautiously to preserve the CPA’s objective of speedy, inexpensive redressal (Preamble, CPA, 2019), avoiding collateral challenges that erode consumer fora’s finality. Key arguments include:

1. Exhaustion of Statutory Remedies

Direct writs bypass the Act’s graduated appeals (Sections 41, 47, 58 of the 2019 Act), available even for appellate NCDRC orders via Article 227. As held in Cicily Kallarackal, entertaining writs where appeals exist “would not be a proper exercise of jurisdiction,” frustrating legislative intent.

Supreme Court appeals under Section 67 are confined to original NCDRC jurisdiction (Sections 58(1)(a)(i) and (ii)), leaving appellate orders (Section 58(1)(a)(iii)) to High Courts under Article 227—premature Article 226 filings thus multiply litigation unnecessarily.

It would be apropos to refer to Whirlpool Corporation v. Registrar of Trade Marks (1999) 1 SCC 242, wherein the Supreme Court held that “when a right or liability is created by a statute which gives a special remedy for enforcing it, the remedy provided by that statute only must be availed of.” This principle applies with full force to consumer disputes where the CPA provides a complete Code.

2. Promotion of Judicial Economy and Forum Discipline

Routine entertainment burdens constitutional courts with matters suited for specialized fora, diluting the efficiency mandates of Sections 47 and 58 of the 2019 Act. Sahu Land Developers warns that this invites “forum-shopping,” especially post-Siddhartha Mookerjee, where erroneous jurisdictional claims (e.g., filing in Delhi for pan-India disputes) waste judicial resources.

It would be trite to refer to Rikhab Chand Jain v. Union of India (2025) LiveLaw (SC) 1129 wherein the Apex Court recently deprecated the practice of High Courts entertaining writs when appropriate remedy exists before a different jurisdiction of the same High Court, stating that such approach leads to “procedural chaos and forum shopping.”

3. Limited Scope of Interference

Article 226 is not appellate; it targets only “exceptional circumstances” like jurisdictional overreach or procedural infirmities (Universal Sompo). Mere errors of fact or law, absent perversity, fail this threshold. As Ibrat Faizan clarified, re-appreciation of evidence undermines NCDRC’s expertise in consumer matters.

In Surya Dev Rai v. Ram Chander Rai (2003) 6 SCC 675, the Supreme Court held:

“Be it a writ of certiorari or the exercise of supervisory jurisdiction, none is available to correct mere errors of fact or of law unless the following requirements are satisfied: (i) the error is manifest and apparent on the face of the proceedings such as when it is based on clear ignorance or utter disregard of the provisions of law, and (ii) a grave injustice or gross failure of justice has occasioned thereby.”

Invoking Article 226 prematurely also risks inconsistent rulings, conflicting with the Act’s uniformity goal and potentially creating conflicting precedents across different High Courts on similar consumer protection issues.

4. Balancing Consumer Protection with Finality

While the CPA prioritizes consumers (Section 2(9)), unchecked writs delay enforcement under Section 71 (execution provisions), ironically harming complainants. Punjab National Bank (Delhi HC) highlights how non-jurisdictional filings exacerbate delays, advocating strict adherence to cause of action tests.

Reference to State of Karnataka v. Vishwabharathi House Building Coop. Society (2003) 2 SCC 412 is worthwhile, wherein while upholding the constitutional validity of the Consumer Protection Act, the Supreme Court observed:

“The provisions relating to power to approach appellate court by a party aggrieved by a decision of the forums/State Commissions as also the power of the High Court and this Court under Articles 226/227 of the Constitution of India and Article 32 are adequate safeguards against any order passed by the National Commission.”

This confirms that both statutory appeals and constitutional remedies coexist, but the latter should not be used to bypass the former routinely.

Practical Implications And Guidance

1. Hierarchy Of Remedies

Aggrieved parties—developers or consumers—must prioritize remedies in the following order:

| Priority Level | Remedy | Relevant Provision / Scope |

|---|---|---|

| First | Statutory Appeals | Sections 41, 47, or 58 of the CPA 2019 |

| Second | Supervisory Jurisdiction | Article 227 for NCDRC appellate/revisional orders |

| Third | Writ Jurisdiction | Article 226 in narrow and exceptional cases |

Article 226 may be invoked only in limited situations such as fundamental rights violations, jurisdictional errors, or patent illegality.

This framework, as established in Ibrat Faizan and Universal Sompo, mandates approaching the High Court of the State Commission’s situs (where the original cause of action arose) before considering Supreme Court SLPs under Article 136. This approach curbs delays and promotes judicial efficiency.

2. Territorial Jurisdiction

Post-Siddhartha Mookerjee, the phrase “jurisdictional High Court” means:

- The High Court within whose territorial limits the original cause of action arose

- Not the High Court where the NCDRC is located (Delhi)

- Not the High Court where the State Commission from which the appeal arose is located, if different from where the cause of action originated

3. Execution Challenges

For execution challenges, Palm Groves Cooperative Housing Society Ltd. v. M/s Magar Girme and Gaikwad Associates (2025 INSC 456) clarifies that appeals lie only to the next consumer level, with no further revision, thereby streamlining enforcement.

However, gross procedural violations or jurisdictional errors in execution proceedings may still warrant Article 227 intervention.

4. When Article 226 May Be Appropriate

Despite the general rule of restraint, Article 226 may be invoked in exceptional cases:

- Fundamental Rights Violations: Where consumer forum orders violate Article 14, 19, or 21

- Complete Lack Of Jurisdiction: Where the forum assumed jurisdiction it never had

- Violation Of Natural Justice: Where a fair hearing was denied and no effective statutory remedy exists

- Patent Illegality: Where the order is contrary to express statutory provisions

Authority

In Associated Cement Companies Ltd. v. P.N. Sharma, AIR 1965 SC 1595, the Supreme Court held that tribunals fall within the definition of “authority” under Article 226, but cautioned:

“The High Court should not ordinarily issue a writ of certiorari quashing the decision of an inferior tribunal unless the court is satisfied that the tribunal has acted without jurisdiction or in excess of its jurisdiction, or has failed to exercise its jurisdiction or that it has acted in violation of principles of natural justice.”

Conclusion

The jurisprudence establishes a clear hierarchy: statutory remedies first, Article 227 supervisory jurisdiction second, and Article 226 writ jurisdiction only in exceptional circumstances. This balanced approach enhances consumer access to justice while upholding judicial hierarchy, minimizing abuse, and ensuring the CPA’s welfare ethos endures.

Parties challenging NCDRC orders must:

- Plead exceptional grounds explicitly with supporting affidavits

- Approach the correct jurisdictional High Court (based on cause of action, not NCDRC location)

- First exhaust or demonstrate the inadequacy of statutory remedies

- Limit prayers to jurisdictional corrections rather than merit review

This framework ensures the Consumer Protection Act’s twin objectives—speedy redressal and effective consumer protection—are achieved without overwhelming constitutional courts or creating judicial chaos through forum shopping and premature constitutional challenges.

The consistent judicial message is clear: constitutional jurisdiction is a safety valve, not a bypass.