The National Herald Case: Background And Context

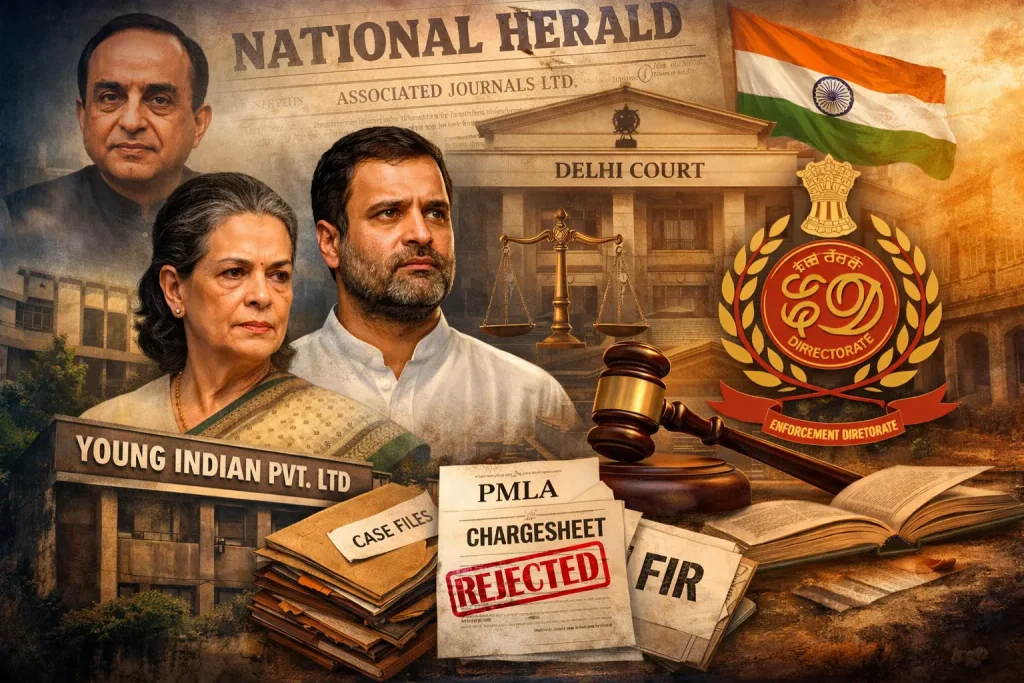

The National Herald case is not just another criminal dispute. It is a rare intersection of history, politics, corporate control, criminal law, and constitutional principles, unfolding over more than a decade. What began as a private complaint questioning the fate of a once-iconic nationalist newspaper gradually transformed into one of the most politically charged legal battles in independent India.

With the Delhi Rouse Avenue Court’s order of December 16, 2025, refusing to take cognisance of the Enforcement Directorate’s prosecution, the case has entered a crucial new phase. To understand why this order matters—and what it does not decide—it is necessary to trace the entire journey of the case from its origins.

This article does exactly that.

The Birth Of National Herald And Associated Journals Ltd

National Herald was founded in 1938 by Jawaharlal Nehru as a newspaper that would articulate the voice of India’s freedom movement. It was published by Associated Journals Ltd (AJL), a public limited company whose shareholders included several prominent freedom fighters.

For decades, National Herald functioned as a political and ideological platform rather than a profit-driven enterprise. Over time, however, financial difficulties mounted. By the early 2000s, the newspaper ceased publication, leaving AJL burdened with debt—but still owning valuable real estate assets across Delhi, Mumbai, Lucknow, Patna, and other cities.

These properties would later become the centre of controversy.

The Congress Party Loan And AJL’s Financial Crisis

Between 2002 and 2011, the All India Congress Committee (AICC) advanced an interest-free loan of approximately ₹90 crore to AJL. According to the Congress party, this was meant to keep the newspaper afloat and protect its legacy.

AJL, however, failed to revive operations or repay the loan.

Nature Of The Transaction

- The transaction involved an interest-free loan from a political party.

- The borrower was a public limited company historically linked to the party.

- No immediate criminal allegations were raised at this stage.

At this stage, the matter was entirely internal and civil in nature—a political party extending funds to a company historically linked to it.

The legal trouble began only after a major corporate restructuring.

The Entry of Young Indian Pvt. Ltd

In 2010, a new company named Young Indian Pvt. Ltd (YIL) was incorporated. Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi each held 38% shares, making them the majority shareholders. The remaining shares were held by senior Congress leaders.

In 2011, AJL transferred almost all of its equity—representing control over its assets—to Young Indian for a nominal consideration. The AICC’s loan to AJL was effectively assigned to Young Indian, which then converted it into equity.

According to the complainant, this transaction resulted in Young Indian acquiring control over AJL’s assets, worth thousands of crores, for a negligible amount.

This restructuring triggered criminal allegations.

The 2012 Private Criminal Complaint

In 2012, Dr. Subramanian Swamy filed a private criminal complaint before a Delhi court alleging:

- Criminal breach of trust

- Cheating

- Criminal conspiracy

Core Allegation and Argument

His argument was simple but explosive:

that Congress party funds were used in a manner that ultimately benefited private individuals, and that the restructuring was a colourable device to transfer valuable assets without fair consideration.

Importantly, this was not a police FIR. It was a private complaint under the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Years of Litigation and Preliminary Battles

From 2013 onwards, the case went through repeated legal challenges:

- Summoning orders were contested

- Petitions were filed before the Delhi High Court

- The Supreme Court intervened at various stages

While the courts allowed the proceedings to continue, they repeatedly clarified that no finding on guilt was being recorded at preliminary stages.

For years, the matter remained a trial court criminal case, moving slowly, attracting public debate but limited enforcement action.

That changed with the entry of the Enforcement Directorate.

The Enforcement Directorate and the PMLA Angle

The Enforcement Directorate (ED) began investigating the case under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), treating the alleged cheating and conspiracy as predicate offences.

Under PMLA, money laundering is a derivative offence—it can exist only if there is a legally recognised underlying criminal offence.

In April 2025, the ED filed its prosecution complaint (commonly referred to as a chargesheet) before the Rouse Avenue Court, naming Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi, and others.

This was the first time the case moved from a private criminal dispute to a full-fledged economic offence prosecution with serious consequences.

The Central Legal Question Before the Trial Court

When the ED’s complaint came up for consideration, the trial court was not asked to decide whether:

- assets were actually misappropriated, or

- the Gandhis gained personal benefit

Instead, the court faced a threshold legal issue:

Can a PMLA prosecution be sustained when it is based on a private criminal complaint and not on a registered FIR for a scheduled offence?

This procedural question would decide the immediate fate of the ED’s case.

Chronology of Key Developments

| Year | Development |

|---|---|

| 2010 | Incorporation of Young Indian Pvt. Ltd (YIL) |

| 2011 | AJL transferred almost all of its equity to Young Indian for a nominal consideration |

| 2012 | Dr. Subramanian Swamy filed a private criminal complaint before a Delhi court |

| 2013 onwards | Repeated legal challenges before the trial court, Delhi High Court, and Supreme Court |

| April 2025 | The ED filed its prosecution complaint before the Rouse Avenue Court |

The December 16, 2025 Verdict: What the Court Held

On December 16, 2025, the Special Judge at Delhi’s Rouse Avenue Court refused to take cognisance of the ED’s prosecution complaint.

The court held that:

- A money-laundering case must rest on a legally recognised predicate offence

- In the present matter, the ED’s case was anchored to a private complaint, not a police FIR

- This procedural foundation was insufficient under the PMLA framework

As a result, the court declined to proceed further with the ED’s case in its present form.

What the Verdict Means—and What It Does Not

It is crucial to understand the limited but significant scope of this order.

| What It Means | What It Does Not Mean |

|---|---|

| The ED cannot proceed with its current PMLA prosecution | It is not an acquittal |

| The court found a procedural defect, not factual innocence | It does not declare the transactions legal |

| The ruling reinforces the principle that process matters as much as allegations | It does not bar appeals or fresh proceedings |

The ED retains the right to challenge the order or correct procedural shortcomings.

Political Reactions and Public Debate

Predictably, the verdict sparked strong political reactions.

- The Congress party described the order as vindication and proof of political misuse of investigative agencies.

- The BJP responded by asserting that the case is far from over and that no court has cleared the accused on merits.

Legal experts, however, largely agree on one point:

this verdict is a textbook example of procedural scrutiny, not political adjudication.

What Lies Ahead

The National Herald case is unlikely to end here. Possible next steps include:

- An appeal by the ED

- Re-initiation of proceedings with a different procedural foundation

- Continuation of the original private complaint

- Further constitutional challenges on the scope of PMLA

In legal terms, the case has paused—not concluded.

Conclusion: A Case That Defines Legal Boundaries

The National Herald case is ultimately less about personalities and more about how far criminal law can stretch into political and corporate arrangements.

The December 2025 verdict reaffirms an essential principle of Indian criminal jurisprudence:

Even the most serious allegations must stand on correct legal foundations.

Whether the story ends in exoneration, prosecution, or prolonged litigation will depend not on headlines—but on how carefully the law is followed in the next chapter.