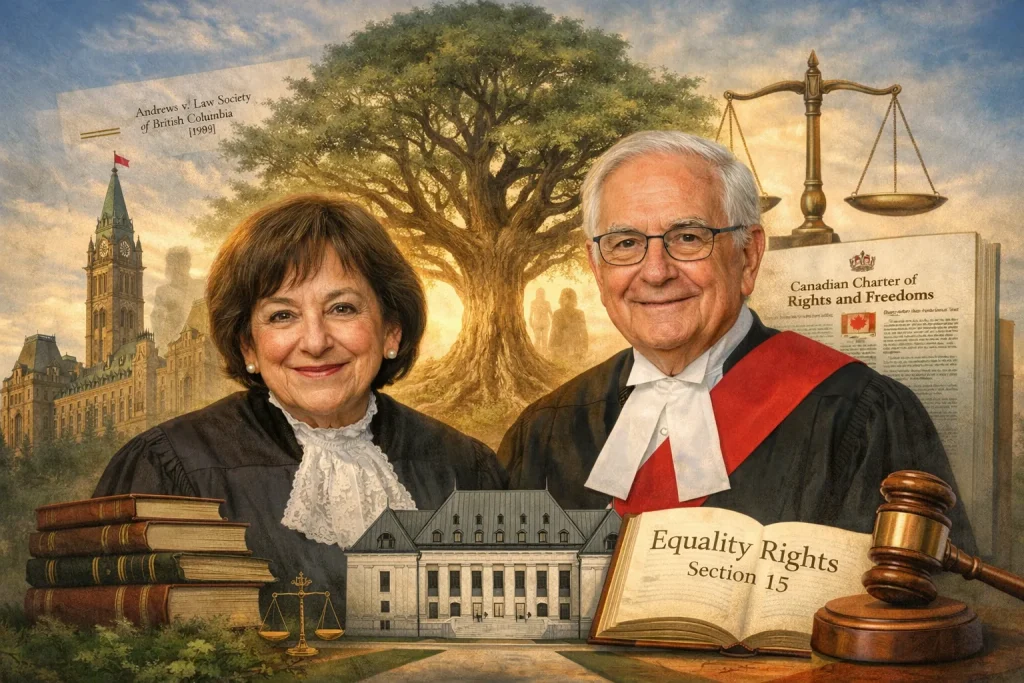

Justice Rosalie Abella, Justice Frank Iacobucci, and the Living Tree of Canadian Law

Canadian constitutional law has evolved not only through statutes and judgments, but through jurists who understood law as a social and moral force. A remarkable public dialogue involving Justice Rosalie Silberman Abella and Justice Frank Iacobucci, both former judges of the Supreme Court of Canada, offers a rare insight into how Canadian law consciously departed from rigid formalism and developed a human-centred constitutional tradition.

This conversation illuminates the foundations of substantive equality, judicial independence, and the uniquely Canadian commitment to the Living Tree doctrine.

Justice Rosalie Abella: Equality as Lived Reality

Justice Rosalie Abella served on the Supreme Court of Canada from 2004 to 2021 and is globally recognised for shaping Canadian equality jurisprudence. Her legal philosophy was deeply influenced by her background as the child of Holocaust survivors, an immigrant to Canada, and one of only a handful of women in law school at the time.

Before joining the Supreme Court, Justice Abella chaired the Royal Commission on Equality in Employment (1984), where she articulated a concept of equality that rejected mere formal sameness. She argued that discrimination arises when arbitrary barriers prevent individuals from fully participating in society, regardless of merit.

This understanding later became foundational to Canadian constitutional law.

From Formal Equality to Substantive Equality

Canadian law made a decisive shift away from the idea that equality means treating everyone identically. Justice Abella explained that formal equality—borrowed from early American constitutional thought—fails to address real disadvantage.

- Treating unequal situations the same often entrenches injustice rather than curing it.

This principle was constitutionally affirmed in Andrews v. Law Society of British Columbia (1989), where the Supreme Court of Canada interpreted Section 15 of the Charter for the first time. The Court held that equality requires recognition, accommodation, and respect for difference, rather than uniform treatment.1

Significantly, Andrews concerned a citizenship requirement that barred a non-citizen from practising law—an issue mirroring the historical exclusion faced by Justice Abella’s father. The judgment struck down the requirement as discriminatory, embedding substantive equality into Canadian constitutional doctrine.

Justice Frank Iacobucci and the Institutional Evolution of Rights

Justice Frank Iacobucci, who served on the Supreme Court from 1991 to 2004, played a pivotal role in shaping Charter jurisprudence during its formative decades. His reflections situate equality within a broader institutional framework, emphasizing that constitutional interpretation is a responsibility assigned to courts by democratic choice.

The adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 fundamentally transformed the judicial role. Unlike the pre-Charter era—dominated by federalism disputes under the British North America Act—the Charter required courts to engage directly with questions of dignity, liberty, and equality.

Cases such as R. v. Oakes (1986) established that constitutional rights are enforceable limits on state power, subject only to strict justification.2

The Living Tree Doctrine: Canada’s Constitutional Identity

A defining feature of Canadian constitutionalism is the Living Tree doctrine, first articulated by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the Persons Case (Edwards v. Canada, 1929). Rejecting narrow originalism, Lord Sankey held that a constitution must grow and adapt to changing social realities.3

This approach has consistently guided Canadian courts in interpreting rights expansively and purposively.

Later decisions such as Hunter v. Southam Inc. (1984) and Big M Drug Mart Ltd. (1985) reinforced the principle that constitutional interpretation must be generous and contextual, focusing on the protection of human dignity rather than historical technicalities.45

Judicial Independence and the Myth of “Judicial Activism”

The discussion directly challenges the critique that rights-based adjudication amounts to judicial overreach. In Canada, courts do not claim authority unilaterally; they exercise authority explicitly granted by the Constitution.

The judiciary’s insulation from electoral pressure exists precisely so it can protect minorities and unpopular interests—an idea affirmed in cases such as Reference re Secession of Quebec (1998), where the Court emphasised constitutionalism, democracy, and the rule of law as interdependent principles.6

Accusations of “activism” often reflect dissatisfaction with outcomes rather than flaws in reasoning. Canadian courts have repeatedly held that enforcing constitutional limits is not intrusion, but obligation.

Equality, Citizenship, and Access to the Legal Profession

Citizenship-based exclusions once prevented skilled immigrants from fully participating in Canadian professional life. Canadian equality jurisprudence now recognises that neutral rules can produce discriminatory effects.

This insight underpins later cases such as Law v. Canada (1999) and Withler v. Canada (2011), which refined equality analysis by focusing on impact, context, and dignity, rather than mechanical comparison.78

The Canadian approach ensures that equality remains responsive to lived realities rather than frozen abstractions.

Canada’s Global Constitutional Influence

Canadian constitutional reasoning now influences courts worldwide, including the South African Constitutional Court, the European Court of Human Rights, and courts in Israel and the United Kingdom. Decisions expanding protections for gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and reproductive autonomy have drawn upon Canada’s purposive interpretive framework.

Cases such as Vriend v. Alberta (1998) and R. v. Morgentaler (1988) demonstrate how Canadian courts have addressed controversial issues by grounding rights in dignity and substantive equality rather than political expediency.910

Conclusion: Canadian Law as Moral Responsibility

The reflections of Justices Abella and Iacobucci reveal why Canadian law occupies a distinctive place in global constitutionalism. Canadian courts have chosen to interpret rights not merely as historical text, but as living commitments to fairness, inclusion, and human dignity.

In doing so, Canadian constitutional law answers not only the question of what the law is, but what the law ought to be.

End-Notes

- Andrews v. Law Society of British Columbia, [1989] 1 SCR 143.

- R. v. Oakes, [1986] 1 SCR 103.

- Edwards v. Canada (Attorney General), [1930] AC 124 (PC).

- Hunter v. Southam Inc., [1984] 2 SCR 145.

- R. v. Big M Drug Mart Ltd., [1985] 1 SCR 295.

- Reference re Secession of Quebec, [1998] 2 SCR 217.

- Law v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration), [1999] 1 SCR 497.

- Withler v. Canada (Attorney General), 2011 SCC 12.

- Vriend v. Alberta, [1998] 1 SCR 493.

- R. v. Morgentaler, [1988] 1 SCR 30.

Also Read:

Partner Lawyers in Canada – Search by City

| Eastern Canada | Central Canada | Western Canada |

|---|---|---|

| Lawyers in Montreal | Lawyers in Ottawa | Lawyers in Edmonton |

| Lawyers in Toronto | Lawyers in Vancouver |