Introduction

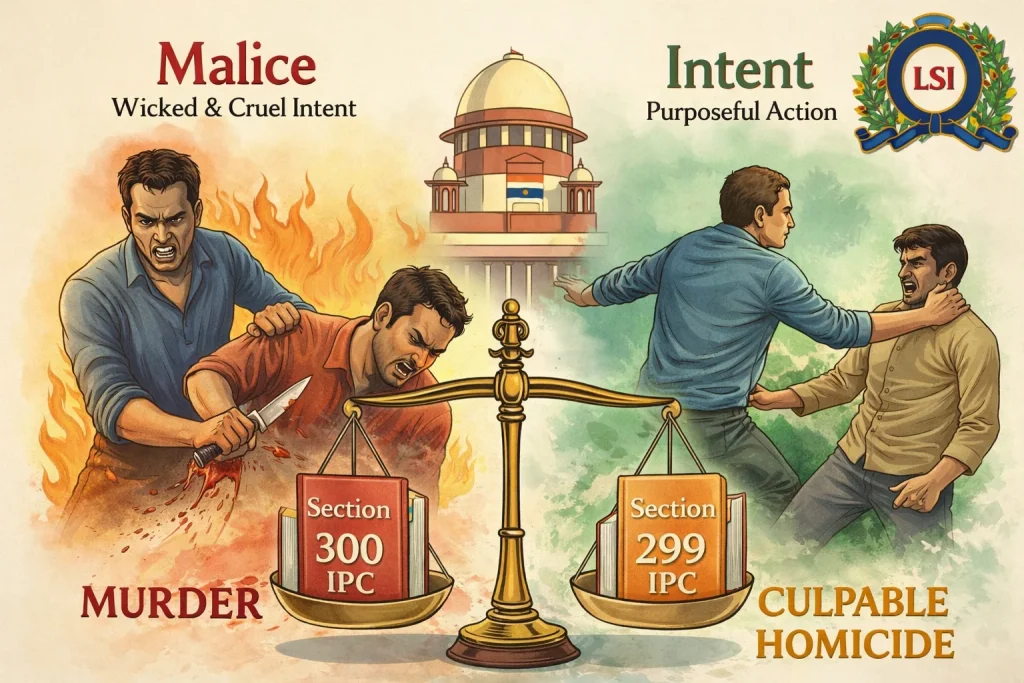

The distinction between intent and malice forms one of the most fundamental yet complex aspects of criminal jurisprudence in India. These two concepts, while often used interchangeably in common parlance, carry distinct legal meanings that can determine whether an act constitutes murder or culpable homicide not amounting to murder. The difference between these classifications is not merely academic—it can mean the difference between a death sentence or life imprisonment and a significantly reduced sentence of up to ten years.

In the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC), the legislature has carefully crafted provisions that distinguish between different degrees of culpable homicide. Section 299 IPC defines culpable homicide, while Section 300 IPC defines murder as an aggravated form of culpable homicide. The relationship between these sections has been the subject of extensive judicial interpretation over the decades, with courts attempting to draw clear lines between acts committed with different mental states.

Intent, in legal terminology, refers to the purpose or objective behind an action. It is the conscious decision to engage in conduct that one knows will produce a particular result. When a person acts with intent, they have a clear understanding of what they are doing and the consequences that will follow. In criminal law, intent is often described as the mens rea or the guilty mind that accompanies the actus reus or the guilty act. The presence of intent transforms what might otherwise be an accident into a criminal offense.

Malice, on the other hand, carries a more sinister connotation. It implies not just the intention to cause harm but also an element of wickedness, cruelty, or ill-will. Malice aforethought, a term borrowed from English common law, suggests premeditation and deliberation. It indicates that the accused not only intended to cause the harm but did so with a depraved or evil state of mind. In the context of murder, malice can be express (where there is a clear intention to kill) or implied (where the circumstances of the killing demonstrate a reckless disregard for human life).

The IPC recognizes that not all killings are equal. While all murders involve the intentional taking of human life, the law provides certain exceptions under Section 300 that reduce what would otherwise be murder to culpable homicide not amounting to murder. These exceptions recognize situations where, despite the presence of intent to cause death or bodily injury likely to cause death, the circumstances surrounding the act mitigate the moral culpability of the accused. These exceptions include grave and sudden provocation (Exception 1), exceeding the right of private defense (Exception 2), acts done by public servants exceeding their lawful powers (Exception 3), sudden fights without premeditation (Exception 4), and consent of the victim in certain circumstances (Exception 5).

The recent Supreme Court judgment in Surender Kumar v. State of Himachal Pradesh (2025) provides valuable insights into how courts analyze the mental state of an accused and determine whether the exceptions to Section 300 IPC apply. The case involved an appellant who was convicted under Section 302 IPC for murder and sought to have his conviction reduced to Section 304 IPC by invoking the exceptions to Section 300. The Supreme Court’s analysis in this case demonstrates the rigorous scrutiny applied to claims that seek to benefit from these exceptions and highlights the importance of evidence in establishing the accused’s state of mind at the time of the offense.

This judgment is particularly significant because it addresses multiple exceptions to Section 300 IPC and explains the specific requirements that must be satisfied for each exception to apply. The Court’s reasoning provides clarity on what constitutes a “sudden fight,” the nature of evidence required to establish self-defense, and the circumstances under which an act can be considered to have been committed in the heat of passion. Moreover, the Court’s emphasis on the nature and number of injuries inflicted, the vulnerability of the victim, and the manner of the attack provides practical guidance for assessing whether an accused acted with malice or mere intent.

Understanding the distinction between intent and malice is crucial not only for legal practitioners and judges but also for law students, researchers, and anyone interested in the criminal justice system. This blog post will examine the Surender Kumar case in detail, analyzing the Court’s reasoning and exploring the broader implications of this judgment for criminal law in India.

Case Background

The case of Surender Kumar v. State of Himachal Pradesh arose from a tragic incident that resulted in the death of an individual due to multiple knife wounds. The appellant, Surender Kumar, was charged with murder under Section 302 of the Indian Penal Code and was subsequently convicted by the trial court. The High Court of Himachal Pradesh affirmed this conviction, leading the appellant to approach the Supreme Court of India.

The factual matrix of the case, as it emerged during the trial, painted a grim picture of violence. The deceased was found to have suffered four knife blows, all inflicted on vital parts of his body. The autopsy report, which became a crucial piece of evidence in the case, revealed the severity of the injuries. The medical examination disclosed that the common carotid artery and subclavian artery of the deceased had been severed. These are major blood vessels that supply blood to the head, neck, and upper limbs. The cutting of these arteries would result in massive hemorrhage and, in the ordinary course of events, would inevitably lead to death within minutes.

The prosecution’s case was built on establishing that the appellant had intentionally inflicted these injuries with the knowledge that they were likely to cause death. The nature of the injuries, their location on vital parts of the body, and the use of a knife as the weapon all pointed toward a deliberate and calculated attack. The prosecution argued that this was a clear case of murder as defined under Section 300 IPC, where the accused had the intention of causing death or causing such bodily injury as was likely to cause death.

The appellant, represented by AOR Ajay Marwah along with advocates Swaroopanand Mishra, Mrigank Bhardwaj, Dhriti Sharma, Rahulkumar, and Rajiv Sethi, challenged his conviction on several grounds. The defense strategy centered on attempting to bring the case within one or more of the exceptions to Section 300 IPC, which would reduce the offense from murder to culpable homicide not amounting to murder, punishable under Section 304 IPC with a significantly lesser sentence.

One of the primary contentions raised by the appellant was that the deceased was addicted to drugs. The defense argued that this fact was relevant because it could explain the circumstances leading to the incident. Additionally, the defense pointed to evidence that loud shouts were heard before the occurrence. Based on these two factors—the deceased’s alleged drug addiction and the sounds of shouting—the appellant contended that the incident must have been preceded by an altercation or quarrel between the parties.

Building on this foundation, the defense argued that the case should fall under either Exception 2 or Exception 4 to Section 300 IPC. Exception 2 deals with situations where a person, in the exercise of the right of private defense, exceeds the power given to them by law and causes the death of the person against whom they are exercising such right. The defense suggested that if there had been an attack by the deceased, the appellant might have been defending himself and, in the process, exceeded the limits of lawful self-defense.

Alternatively, the defense invoked Exception 4, which applies to cases of sudden fights. This exception states that culpable homicide is not murder if it is committed without premeditation in a sudden fight in the heat of passion upon a sudden quarrel, and without the offender having taken undue advantage or acted in a cruel or unusual manner. The defense argued that if the incident occurred during a sudden fight triggered by the altercation, and if the appellant acted in the heat of passion without premeditation, then the offense should be reduced to culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

However, the prosecution, represented by AOR Varinder Kumar Sharma, strongly contested these claims. The State argued that there was no credible evidence to support the defense’s theory of either self-defense or sudden fight. The prosecution emphasized that the appellant had failed to provide any substantive evidence to establish the occurrence of an altercation or attack by the deceased.

A critical weakness in the defense case was the statement of the appellant under Section 313 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC). Section 313 CrPC provides an opportunity for the accused to explain any circumstances appearing in the evidence against them. It is a valuable safeguard that allows the accused to put forth their version of events. However, in this case, the appellant’s statement under Section 313 CrPC was one of complete denial. He did not claim that the deceased had attacked him, nor did he allege that he had suffered any injury or harm at the hands of the deceased. He did not raise any plea of self-defense or provocation.

Furthermore, the defense did not lead any evidence to support their contentions. In criminal trials, while the burden of proving the guilt of the accused beyond reasonable doubt lies on the prosecution, when an accused seeks to benefit from an exception to Section 300 IPC, they must provide some material or evidence to show that the case falls within that exception. The complete absence of defense evidence and the lack of any specific plea in the Section 313 statement significantly weakened the appellant’s case.

The trial court, after considering all the evidence, convicted the appellant under Section 302 IPC and sentenced him accordingly. The High Court of Himachal Pradesh, in its appellate jurisdiction, examined the evidence afresh and found no reason to interfere with the trial court’s findings. The High Court affirmed both the conviction and the sentence, leading to the present appeal before the Supreme Court.

Before the Supreme Court, the Division Bench comprising Justice Manoj Misra and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan was tasked with examining whether the High Court had erred in affirming the conviction under Section 302 IPC. The appellant urged the Court to take a lenient view and either convert the conviction to one under Section 304 IPC or at least reduce the period of sentence. The appellant’s counsel argued that the circumstances of the case warranted the application of one or more exceptions to Section 300 IPC.

The Supreme Court’s task was to carefully analyze the evidence on record, examine the applicability of the exceptions claimed by the appellant, and determine whether the case was one of murder or culpable homicide not amounting to murder. The Court had to assess whether the appellant had acted with malice aforethought or whether the circumstances mitigated his culpability to the extent that the offense should be classified as culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

Court’s Observations

The Supreme Court’s analysis in the Surender Kumar case provides a masterclass in judicial reasoning on the distinction between murder and culpable homicide not amounting to murder. The Division Bench of Justice Manoj Misra and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan systematically examined each of the exceptions to Section 300 IPC that the appellant sought to invoke and explained why none of them applied to the facts of this case.

Analysis of Exception 2 (Exceeding Right of Private Defense)

The Court began by addressing the appellant’s claim that the case fell under Exception 2 to Section 300 IPC. This exception applies when a person, in the exercise of the right of private defense of person or property, exceeds the power given to them by law and causes the death of the person against whom they are exercising such right, without premeditation and without any intention of doing more harm than is necessary for the purpose of such defense.

The Court noted that for Exception 2 to apply, there must be evidence to show that the accused or their property was under attack by the deceased. The right of private defense is a well-established principle in criminal law, recognizing that a person has the right to protect themselves and their property from unlawful aggression. However, this right is not absolute and is subject to certain limitations. The force used must be proportionate to the threat, and the person exercising this right must not exceed what is reasonably necessary for defense.

In the present case, the Court observed that there was no evidence whatsoever to show that the deceased had attacked the appellant or posed any threat to him or his property. Crucially, even in his statement under Section 313 CrPC, the appellant did not raise any plea of self-defense. He did not claim that the deceased had attacked him or that he had suffered any injury at the hands of the deceased. The Court also noted that no defense evidence was led to establish that the appellant was acting in self-defense.

Moreover, the Court pointed out that there was no evidence to show that the deceased was armed. This is a significant factor because if the deceased had been armed with a weapon, it could have supported the appellant’s claim that he was defending himself against a threat. The absence of any weapon with the deceased further weakened the self-defense theory.

The Court concluded that in such circumstances, the benefit of Exception 2 would not be available to the appellant. This conclusion is legally sound and reflects the well-established principle that the burden of establishing circumstances that would bring a case within an exception to Section 300 IPC lies on the accused, and mere assertions without supporting evidence are insufficient.

Analysis of Exception 4 (Sudden Fight)

The Court then turned its attention to Exception 4, which the appellant had also invoked. Exception 4 to Section 300 IPC states that culpable homicide is not murder if it is committed without premeditation in a sudden fight in the heat of passion upon a sudden quarrel and without the offender having taken undue advantage or acted in a cruel or unusual manner.

The Court explained that for Exception 4 to apply, the following ingredients must be fulfilled: (i) there should be no premeditation; (ii) there should be a sudden fight; (iii) the act should be committed in the heat of passion; and (iv) the assailant should not have taken any undue advantage or acted in a cruel manner.

The Court noted that the term “fight” has not been defined in the IPC. However, drawing on consistent judicial interpretation, the Court stated that a “fight” implies mutual assault by use of criminal force and not a mere verbal duel. In other words, for Exception 4 to apply, there must be evidence of physical altercation between the parties, with both sides engaging in the use of force.

The Court observed that in the instant case, there was no evidence of any exchange of blows. The appellant had not claimed that there was a physical altercation or that the deceased had assaulted him. The mere fact that loud shouts were heard before the occurrence was insufficient to establish that there was a sudden fight. Shouting or verbal altercation, by itself, does not constitute a “fight” within the meaning of Exception 4.

Even more significantly, the Court focused on the fourth ingredient of Exception 4—that the assailant should not have acted in a cruel or unusual manner. The Court made a critical observation that forms the crux of this judgment: “Moreover, infliction of 4 knife blows to an unarmed person, on vital parts of the body, is indicative of the accused acting in a cruel manner.”

This observation is of immense legal significance. The Court was emphasizing that the manner in which the attack was carried out demonstrated cruelty and malice. The deceased was unarmed and vulnerable. The appellant inflicted not one but four knife blows, all targeted at vital parts of the body. The autopsy report revealed that the common carotid and subclavian arteries were cut, which would result in rapid and massive blood loss leading to death.

The Court’s reasoning reflects the principle that the nature, number, and location of injuries are crucial factors in determining the mental state of the accused. Multiple blows to vital organs suggest a determined and calculated effort to cause death, rather than an impulsive act in the heat of passion. The fact that the victim was unarmed further indicates that the accused had taken undue advantage and acted in a cruel manner.

The Court concluded that the case would not fall under Exception 4 to Section 300 IPC. This conclusion is well-reasoned and supported by the evidence on record. The absence of any evidence of mutual combat, combined with the cruel manner in which the attack was carried out, clearly took the case outside the scope of Exception 4.

Analysis of Exception 1 (Grave and Sudden Provocation)

Although not extensively discussed in the judgment summary, the Court also addressed Exception 1 to Section 300 IPC, which deals with grave and sudden provocation. This exception applies when a person causes death while deprived of the power of self-control by grave and sudden provocation.

The Court held that there was not much evidence on record to disclose that provocation was so grave and sudden that the appellant was deprived of his self-control. For Exception 1 to apply, the provocation must be of such a nature that it would cause a reasonable person to lose self-control. Moreover, the provocation must be sudden, and the act must be committed before there is time for passion to cool down.

In this case, the appellant had not provided any specific evidence of what provocation, if any, he had received from the deceased. The mere allegation that the deceased was addicted to drugs or that loud shouts were heard was insufficient to establish grave and sudden provocation. The Court’s conclusion that Exception 1 did not apply is consistent with the established legal principle that provocation must be proved by credible evidence and cannot be inferred from mere speculation.

Assessment of Injuries and Intent

A crucial aspect of the Court’s reasoning was its analysis of the nature and extent of injuries inflicted on the deceased. The Court noted that the autopsy report revealed four knife blows on vital parts of the body, with the common carotid and subclavian arteries being cut. The Court observed that “injuries found on the body of the deceased in ordinary course would have resulted in death.”

This observation is significant because it establishes that the injuries were of such a nature that death was the natural and probable consequence. Under Section 300 IPC, if a person does an act with the intention of causing such bodily injury as is likely to cause death, it amounts to murder. The nature and location of the injuries in this case clearly indicated that the appellant intended to cause injuries that were likely to result in death.

The Court’s emphasis on the fact that the deceased was unarmed is also noteworthy. When an armed person attacks an unarmed person, it demonstrates a significant power imbalance and suggests that the accused had taken undue advantage. This factor is relevant not only for Exception 4 but also for assessing the overall culpability of the accused.

Critical Analysis

From a legal perspective, the Supreme Court’s judgment in this case is sound and well-reasoned. The Court has correctly applied the principles governing the exceptions to Section 300 IPC and has emphasized the importance of evidence in establishing circumstances that would reduce murder to culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

However, one aspect that could have been explored in greater detail is the psychological state of the appellant at the time of the offense. While the Court has rightly focused on the objective factors such as the nature of injuries and the absence of evidence of provocation or self-defense, a more detailed examination of the appellant’s mental state could have provided additional insights.

The judgment also highlights a common problem in criminal trials—the failure of the accused to properly articulate their defense in the Section 313 CrPC statement. Many accused persons, either due to lack of legal awareness or poor legal representation, fail to raise specific defenses in their Section 313 statements, which can significantly prejudice their case. This judgment serves as a reminder of the importance of the Section 313 statement and the need for accused persons to clearly state their version of events.

Another interesting aspect is the Court’s interpretation of “cruel manner” in the context of Exception 4. The Court has held that inflicting multiple knife blows on vital parts of an unarmed person’s body constitutes acting in a cruel manner. This interpretation is consistent with the humanitarian principles underlying criminal law, which seek to distinguish between different degrees of moral culpability. An attack that is particularly brutal or that takes advantage of the victim’s vulnerability is deserving of greater punishment than one that occurs in more equal circumstances.

Impact

The Supreme Court’s judgment in Surender Kumar v. State of Himachal Pradesh has significant implications for criminal jurisprudence in India, particularly in cases involving charges of murder and culpable homicide. The decision clarifies several important legal principles and provides guidance for courts, prosecutors, and defense lawyers in similar cases.

Clarification of the Distinction Between Intent and Malice

One of the most important contributions of this judgment is its clarification of the distinction between intent and malice in the context of murder cases. The Court has demonstrated that not all intentional killings are equal. While intent refers to the purpose or objective behind an action, malice implies an element of wickedness, cruelty, or ill-will that aggravates the moral culpability of the accused.

The Court’s analysis shows that the presence of malice can be inferred from the circumstances of the case, particularly the manner in which the offense was committed. Factors such as the number of injuries inflicted, their location on vital parts of the body, the vulnerability of the victim, and the use of excessive force all point toward the presence of malice. This understanding is crucial for distinguishing between murder and culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

Guidance on Application of Exceptions to Section 300 IPC

The judgment provides detailed guidance on the application of exceptions to Section 300 IPC, particularly Exceptions 2 and 4. The Court has emphasized that these exceptions are not to be applied mechanically but require careful examination of the evidence in each case.

For Exception 2 (exceeding the right of private defense) to apply, there must be credible evidence that the accused was acting in self-defense. Mere assertions without supporting evidence are insufficient. The accused must show that they were under attack or faced a threat, and that they exceeded the limits of lawful defense without premeditation.

For Exception 4 (sudden fight) to apply, there must be evidence of mutual combat, not just a one-sided attack. The term “fight” implies an exchange of blows and the use of criminal force by both parties. Moreover, even if there is evidence of a sudden fight, the exception will not apply if the accused acted in a cruel manner or took undue advantage of the victim.

This guidance is valuable for trial courts and appellate courts in assessing whether a particular case falls within one of the exceptions to Section 300 IPC. It also serves as a reminder to defense lawyers that they must lead credible evidence to establish circumstances that would bring the case within an exception.

Importance of the Section 313 CrPC Statement

The judgment highlights the critical importance of the statement of the accused under Section 313 CrPC. This statement provides an opportunity for the accused to explain the circumstances appearing in the evidence against them and to put forth their version of events. However, as this case demonstrates, a statement of mere denial without specific explanations or defenses can significantly prejudice the accused’s case.

Defense lawyers must ensure that their clients provide detailed and specific statements under Section 313 CrPC, particularly when seeking to invoke exceptions to Section 300 IPC. If the accused claims self-defense, provocation, or sudden fight, these defenses must be clearly articulated in the Section 313 statement. Failure to do so can result in the court concluding that these defenses are afterthoughts and not genuine.

Emphasis on Medical Evidence

The judgment underscores the importance of medical evidence, particularly autopsy reports, in murder cases. The Court relied heavily on the autopsy report to assess the nature and extent of injuries and to determine whether the injuries were likely to cause death in the ordinary course of events.

Medical evidence provides objective and scientific data that can corroborate or contradict other evidence in the case. In this case, the autopsy report revealed that major blood vessels had been severed, which established that the injuries were of a fatal nature. This evidence was crucial in supporting the prosecution’s case that the accused had the intention of causing death or causing such bodily injury as was likely to cause death.

Prosecutors should ensure that medical evidence is properly collected, preserved, and presented in court. Defense lawyers, on the other hand, should carefully examine medical evidence to identify any inconsistencies or alternative explanations that could support their client’s case.

Implications for Sentencing

While the primary focus of this judgment is on the distinction between murder and culpable homicide not amounting to murder, it also has implications for sentencing. The Court refused to reduce the sentence imposed on the appellant, finding no mitigating circumstances that would justify a lesser punishment.

This aspect of the judgment reinforces the principle that sentencing must be proportionate to the gravity of the offense and the culpability of the offender. In cases involving brutal attacks on vulnerable victims, courts are unlikely to take a lenient view, even if the accused has no prior criminal record or other mitigating factors.

The judgment also serves as a deterrent to potential offenders, sending a clear message that violent crimes, particularly those involving cruelty and malice, will be met with severe punishment. This deterrent effect is an important function of criminal law and contributes to the maintenance of public order and safety.

Impact on Legal Practice

For legal practitioners, this judgment provides valuable insights into how courts analyze evidence and apply legal principles in murder cases. Defense lawyers must be aware that seeking to invoke exceptions to Section 300 IPC requires more than mere assertions—it requires credible evidence and a coherent narrative that explains the circumstances of the offense.

Prosecutors, on the other hand, must focus on establishing not just the fact of the killing but also the mental state of the accused. Evidence of the manner in which the offense was committed, the nature and number of injuries, and the vulnerability of the victim can all help establish that the accused acted with malice and not merely with intent.

Broader Societal Implications

Beyond its legal significance, this judgment has broader societal implications. It reflects the judiciary’s commitment to protecting human life and ensuring that those who take lives in a cruel and malicious manner are held accountable. The judgment sends a message that the law will not tolerate violence, particularly when it is directed at vulnerable and unarmed individuals.

The judgment also highlights the importance of evidence-based decision-making in the criminal justice system. Courts must base their decisions on credible evidence and sound legal reasoning, not on speculation or sympathy. This approach ensures fairness and consistency in the administration of justice.

Potential for Future Development

While this judgment provides valuable guidance on the distinction between intent and malice, there is scope for further development of this area of law. Future cases may explore the psychological aspects of criminal behavior in greater depth, examining factors such as mental illness, emotional disturbance, and the impact of substance abuse on criminal responsibility.

There is also scope for developing more nuanced approaches to sentencing in murder cases. While the law recognizes exceptions to Section 300 IPC that reduce the offense to culpable homicide not amounting to murder, there may be other circumstances that, while not falling within these exceptions, nevertheless warrant a more lenient approach to sentencing. Courts may need to develop a more sophisticated framework for assessing mitigating and aggravating factors in murder cases.

FAQs

Q1: What is the difference between intent and malice in criminal law?

Intent and malice are related but distinct concepts in criminal law. Intent refers to the purpose or objective behind an action—it is the conscious decision to engage in conduct that one knows will produce a particular result. When a person acts with intent, they have a clear understanding of what they are doing and the consequences that will follow. For example, if a person deliberately shoots another person, they have the intent to cause injury or death.

Malice, on the other hand, goes beyond mere intent and implies an element of wickedness, cruelty, or ill-will. Malice suggests not just the intention to cause harm but also a depraved or evil state of mind. In the context of murder, malice aforethought indicates that the accused not only intended to cause death but did so with premeditation and deliberation, or in a manner that demonstrates a reckless disregard for human life.

The distinction between intent and malice is important because it can determine the classification of an offense. All murders involve intent (the intention to cause death or bodily injury likely to cause death), but murder also requires malice or circumstances that demonstrate a higher degree of moral culpability. The exceptions to Section 300 IPC recognize situations where, despite the presence of intent, the circumstances mitigate the moral culpability of the accused, reducing the offense from murder to culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

Q2: What are the exceptions to Section 300 IPC, and when do they apply?

Section 300 IPC defines murder as an aggravated form of culpable homicide. However, the section also provides five exceptions that reduce what would otherwise be murder to culpable homicide not amounting to murder, punishable under Section 304 IPC with a lesser sentence.

Exception 1 deals with grave and sudden provocation. It applies when a person causes death while deprived of the power of self-control by grave and sudden provocation. The provocation must be of such a nature that it would cause a reasonable person to lose self-control, and the act must be committed before there is time for passion to cool down.

Exception 2 deals with exceeding the right of private defense. It applies when a person, in the exercise of the right of private defense of person or property, exceeds the power given to them by law and causes death without premeditation and without any intention of doing more harm than is necessary for defense.

Exception 3 applies to public servants who, in the exercise of their lawful powers, exceed those powers and cause death without malice and in the belief that they are acting lawfully.

Exception 4 deals with sudden fights. It applies when culpable homicide is committed without premeditation in a sudden fight in the heat of passion upon a sudden quarrel, and without the offender having taken undue advantage or acted in a cruel or unusual manner.

Exception 5 applies when a person above eighteen years of age causes the death of another person with that person’s consent.

For any of these exceptions to apply, the accused must provide credible evidence to establish the circumstances that would bring the case within the exception. Mere assertions without supporting evidence are insufficient.

Q3: How do courts determine whether an accused acted in a cruel manner?

Courts assess whether an accused acted in a cruel manner by examining the totality of circumstances surrounding the offense. Several factors are considered, including the nature and number of injuries inflicted, the location of injuries on the body, the vulnerability of the victim, the weapon used, and the manner in which the attack was carried out.

In the Surender Kumar case, the Supreme Court held that inflicting four knife blows on an unarmed person, targeting vital parts of the body, is indicative of acting in a cruel manner. The Court noted that the common carotid and subclavian arteries were severed, which would result in rapid and massive blood loss leading to death. The fact that the victim was unarmed and vulnerable, combined with the deliberate targeting of vital organs, demonstrated cruelty and malice.

Courts also consider whether the accused took undue advantage of the victim. For example, if the accused was armed while the victim was unarmed, or if the accused attacked the victim from behind or when the victim was in a helpless condition, these factors would indicate that the accused acted in a cruel manner and took undue advantage.

The assessment of cruelty is important for determining whether Exception 4 to Section 300 IPC (sudden fight) applies. Even if there is evidence of a sudden fight, the exception will not apply if the accused acted in a cruel or unusual manner. This ensures that the law distinguishes between acts committed in the heat of passion during a fair fight and acts that demonstrate a depraved or malicious state of mind.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s judgment in Surender Kumar v. State of Himachal Pradesh represents a significant contribution to the jurisprudence on the distinction between murder and culpable homicide not amounting to murder. The Court’s detailed analysis of the exceptions to Section 300 IPC and its emphasis on the importance of evidence in establishing these exceptions provide valuable guidance for courts and legal practitioners.

The judgment reinforces the principle that intent and malice are distinct concepts, and that the presence of malice—as evidenced by the cruel manner in which an offense is committed—is a key factor in determining whether an act constitutes murder. The Court’s observation that inflicting multiple knife blows on vital parts of an unarmed person’s body is indicative of acting in a cruel manner establishes an important precedent for future cases.

One of the key takeaways from this judgment is the importance of the Section 313 CrPC statement. Accused persons must use this opportunity to clearly articulate their defense and explain the circumstances of the offense. A statement of mere denial, without specific explanations or defenses, can significantly prejudice the accused’s case and make it difficult to invoke the exceptions to Section 300 IPC.

The judgment also highlights the critical role of medical evidence in murder cases. Autopsy reports and other medical evidence provide objective and scientific data that can establish the nature and extent of injuries and help determine the mental state of the accused. Prosecutors and defense lawyers must pay careful attention to medical evidence and ensure that it is properly presented and analyzed in court.

Looking ahead, this judgment is likely to influence how courts approach similar cases in the future. The principles established in this case—particularly regarding the interpretation of “cruel manner” and the requirements for establishing a “sudden fight”—will serve as important precedents for lower courts. The judgment also provides a framework for assessing the applicability of exceptions to Section 300 IPC, which will help ensure consistency and fairness in the administration of criminal justice.

However, there is scope for further development of this area of law. Future cases may explore the psychological aspects of criminal behavior in greater depth, examining factors such as mental illness, emotional disturbance, and the impact of substance abuse on criminal responsibility. There is also a need for more nuanced approaches to sentencing in murder cases, taking into account a wider range of mitigating and aggravating factors.

The judgment in Surender Kumar v. State of Himachal Pradesh serves as a reminder of the complexity of criminal law and the importance of careful analysis of evidence and legal principles. It demonstrates the judiciary’s commitment to protecting human life and ensuring that those who take lives in a cruel and malicious manner are held accountable. At the same time, it recognizes that not all killings are equal and that the law must distinguish between different degrees of moral culpability.

For legal practitioners, this judgment provides valuable insights into how courts analyze evidence and apply legal principles in murder cases. For law students and researchers, it offers an opportunity to deepen their understanding of the distinction between intent and malice and the exceptions to Section 300 IPC. For the general public, it reinforces the message that the law will not tolerate violence, particularly when it is directed at vulnerable and unarmed individuals.

As the criminal justice system continues to evolve, judgments like this one play a crucial role in shaping legal principles and ensuring that the law remains responsive to the needs of society. The distinction between intent and malice, and the careful application of exceptions to Section 300 IPC, are essential for ensuring that justice is done in each case, balancing the need for punishment and deterrence with the recognition of mitigating circumstances that may reduce the moral culpability of the accused.

How Claw Legaltech Can Help?

Navigating the complexities of criminal law, particularly in cases involving charges of murder and culpable homicide, requires access to comprehensive legal resources, up-to-date case law, and efficient case management tools. Claw Legaltech is a cutting-edge legal technology platform designed to assist lawyers, law students, and litigants in managing their legal matters more effectively.

Legal GPT – AI-Powered Legal Assistance

One of the standout features of Claw Legaltech is Legal GPT, an AI-powered tool that can draft legal documents, answer complex legal queries, and provide relevant citations from case law and statutes. For lawyers handling criminal cases like the Surender Kumar case, Legal GPT can quickly generate drafts of petitions, written arguments, and legal opinions. It can also help in researching the applicability of exceptions to Section 300 IPC by analyzing similar cases and providing relevant precedents. This saves valuable time and ensures that legal arguments are well-supported by authoritative sources.

AI Case Search – Find Relevant Judgments Instantly

The AI Case Search feature allows users to find judgments by keyword or context, making it easy to locate relevant case law on specific legal issues. For instance, if you are working on a case involving the distinction between intent and malice, or the application of Exception 4 to Section 300 IPC, you can use AI Case Search to find judgments that have dealt with similar issues. The platform’s advanced search algorithms ensure that you get the most relevant results quickly, enabling you to build stronger legal arguments based on established precedents.

Case Summarizer – Quick Insights with Citations

Understanding lengthy judgments can be time-consuming, especially when dealing with multiple cases. The Case Summarizer feature provides concise summaries of judgments with proper citations, allowing you to quickly grasp the key points and legal principles established in each case. This is particularly useful for lawyers preparing for hearings or students studying case law. The summaries include the facts of the case, the legal issues involved, the court’s reasoning, and the final decision, giving you a comprehensive overview in a fraction of the time it would take to read the full judgment.

Whether you are a practicing lawyer handling criminal cases, a law student studying criminal jurisprudence, or a litigant seeking to understand your legal rights, Claw Legaltech provides the tools and resources you need to navigate the legal system more effectively. The platform’s combination of AI-powered features and comprehensive legal databases makes it an invaluable resource for anyone involved in legal matters. By leveraging technology to make legal information more accessible and manageable, Claw Legaltech is helping to democratize access to justice and empower legal professionals to serve their clients more effectively.