Importance of Enforcement of Fundamental Rights

The crafters of the Indian Constitution did not find any real value in declaring Fundamental Rights without a mechanism for enforcement. Rights that are unenforceable are merely aspirational ideals; they do not defend individual rights or delimit the arbitrary powers of the State. The Constitution, thus, incorporates judicial remedies to give these rights existence an enforcement, which is a vital distinctive aspect of the Indian constitutional provision.

Constitutional Mechanism for Enforcement

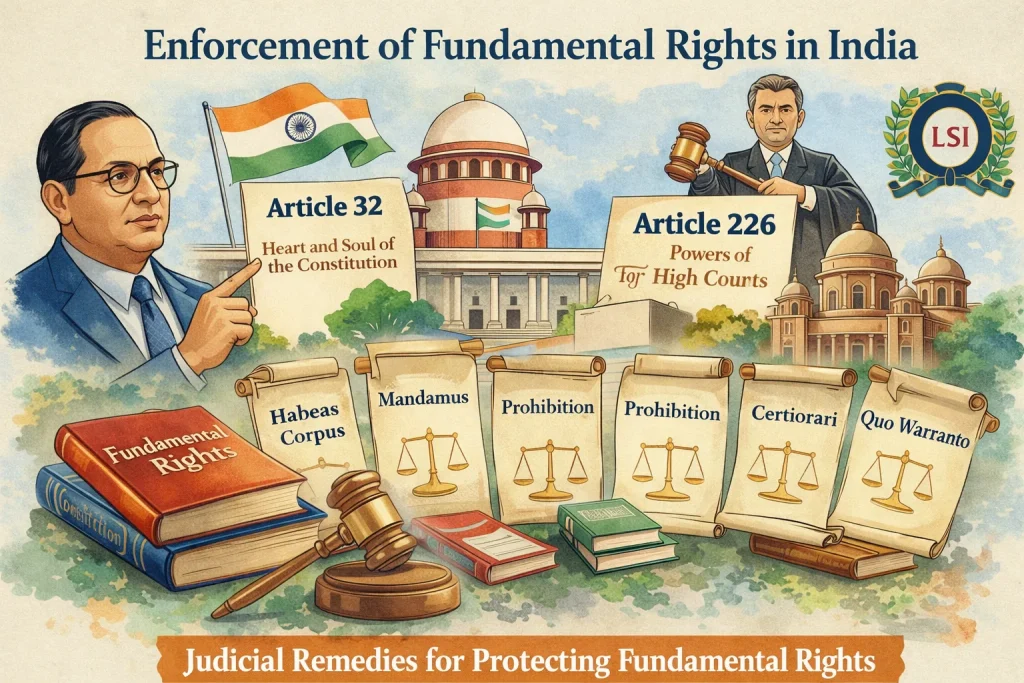

The mechanism for enforcement of Fundamental Rights is in Articles 32 and 226 of the Constitution.

Article 32: The Heart and Soul of the Constitution

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar referred to Article 32 as the “heart and soul” of the Constitution because your right to directly petition the Supreme Court for enforcement of the Fundamental Rights. The right to constitutional remedies is also classified as a Fundamental Right, which gives the right constitutional authority.

Article 32 makes it clear that if any of the rights specified in Part III of the Constitution is violated, the Supreme Court has power of action on that violation by issuing the appropriate writs of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, certiorari and quo warranto to restore law and order and provide remedial action.

Writs Issued Under Article 32

- Habeas Corpus

- Mandamus

- Prohibition

- Certiorari

- Quo Warranto

Article 226: Powers of the High Courts

In addition, Article 226 grants the power to the High Courts to issue any writs beyond the context of Fundamental Rights, “for any other purpose,” which encompasses rights that may be legally recognized but are not Fundamental.

This breadth of power allows the High Courts to be an important vehicle for citizens in search of justice, allowing for speedier access and reduction of the burden on the Supreme Court.

Comparative Scope of Articles 32 and 226

| Provision | Authority | Scope of Power |

|---|---|---|

| Article 32 | Supreme Court | Enforcement of Fundamental Rights under Part III of the Constitution |

| Article 226 | High Courts | Enforcement of Fundamental Rights and other legally recognized rights “for any other purpose” |

Articles 32 and 226 as the Engine of Constitutional Democracy

The relationship of Article 32 and Article 226 is the engine that keeps India’s constitutional democracy functioning by allowing Fundamental Rights to be realized as practical, enduring realities and not merely aspirations or ideals.

Analysis

Articles 32 and 226 are a carefully constructed set of judicial remedies meant to co-exist within India’s constitutional framework. Both articles allow the higher judiciary to protect individual rights from interference by the state, but Articles 32 and 226 are different with respect to character, scope and constitutional philosophy which creates a two tier (but, complementary) remedial scheme.

Distinct Constitutional Roles of Articles 32 and 226

Article 32 has its own particular significance and character as it is itself a Fundamental Right. Anyone whose Fundamental Rights are violated may approach the Supreme Court directly without being first required to pursue another avenue of redress.

Article 32 establishes a convenient predicate of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s designation of the Supreme Court as “protector and guarantor of Fundamental Rights.” The Supreme Court is empowered to issue writs (such as habeas corpus or mandamus) which provide immediate and enforceable redress from arbitrary action of the state.

Evolution of Judicial Interpretation

Over the past decade the Court’s reasoning has been expanded and Judges have recognized that Public Interest Litigations (PILs) also provide ordinary people with access to redress, over the systemic injustices.

The important cases of Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India (1984) and Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978) are among the more recent litmus tests of this precept.

Federal Dimension and Forum Shopping

From the perspective of the federal nature of our Constitution, Article 226 advances decentralized justice by providing remedies to citizens across the states, while easing the Supreme Court’s direct burden.

However, this overlaps cause of action lines leads to what can be described as “forum shopping” whereby litigants are making choices between High Court and Supreme Court based on what they feel would be advantageous for them to litigate in one of them.

High Court Jurisdiction and the Basic Structure Doctrine

The Supreme Court has consistently held in similar jurisprudence as in L. Chandra Kumar v Union of India that High Court jurisdiction under Article 226 is part of the basic structure of the Constitution and unless there is parliamentary method to oust them by the creation of tribunals.

Article 32 – Right to Constitutional Remedies

“Adherence to those rights cannot be enforced if we do not provide remedies to pay heed to those rights… If I was asked to name particular Article in this Constitution as the most important one, I would be unable to name any Article except this one…”

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, one of the founders of the Constitution and chief architect of the document, emphasized the importance of Article 32 in relation to previous discussions regarding fundamental rights.

Ambedkar made a number of critical statements about the importance of litigation if one’s rights violate—including the idea that if descendants of untouchables violate care and disrespect, they will not be able to aggregate and litigate without a remedy, that they would have no recourse, and that their individual dignity is then subject to social discrimination.

Scope and Limitation: Enforcement of Fundamental Rights Only

A key aspect of Article 32 is that it can only be invoked for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights. This stipulates that if someone’s legal right under an ordinary statute has been infringed, it is not possible to approach the Supreme Court directly under Article 32.

You must instead pursue other remedies, including high court jurisdiction under Article 226, or ordinary civil and criminal court remedies.

Judicial Clarification on Limitations

The Supreme Court itself has emphasized this distinction, in State of Orissa v. Madan Gopal Rungta, (1952). Article 32 is simply not available to enforce rights aside from those enumerated in Part III.

The Court made a similar ruling in Charanjit Lal v. Union of India (1950), when it ruled that the mere infringement of a statutory or contractual obligation does not permit a violation claimed under Article 32, unless it took away a Fundamental Right.

Liberal Interpretation of Fundamental Rights

The Court has, however, taken a generous approach to the interpretation of Fundamental Rights, in order not to deny justice to litigants simply based on narrow technicalities.

For example, in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), the Supreme Court gave a broad interpretation of Article 21 that included a number of rights for a dignified life, which expanded the scope for invoking Article 32.

Writ Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court

To properly protect those rights the Supreme Court, by virtue of Clause (1) of Article 32, is empowered to issue one of five available writs, each of which has its own unique objective:

Five Constitutional Writs Under Article 32

| Writ | Meaning and Purpose |

|---|---|

| Habeas Corpus | Meaning “produce the body”, this writ orders the release of a person that is being held in custody without legal grounds to do so. |

| Mandamus | This writ is a command from the Supreme Court to a public authority to comply with a duty it has created by law. |

| Prohibition | This writ is a command from the Supreme Court to protect jurisdiction by prohibiting a lower court or tribunal from exercising jurisdiction. |

| Certiorari | This writ is issued to quash the order of a lower court or tribunal which has acted outside of its jurisdiction. |

| Quo Warranto | This writ investigates the legality of the office being held by any person. |

The incorporation of these five writs, grounded in English common law but now part of Indian jurisprudence, provides the Supreme Court with a very flexible and effective set of remedies to investigate arbitrary actions of the State.

Evolution Through Case Law

Throughout history, Article 32 has become a powerful tool for social justice. For example, in Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India, 1984, the Supreme Court made a positive decision to entertain Public Interest Litigation (PIL) for the purposes of protecting bonded labourers, affirming that, even for the most marginalized persons living without a fundamental ally, each individual can bring a case before the Court.

In Hussa Inara Khatoon v. State of Bihar, 1979, for instance the Court found that the right to a speedy trial could be implied from Article 21, upholding undertrial prisoners’ ability to invoke Article 32.

Impact of Public Interest Litigation

With the advent of Public Interest Litigation starting in the late 1970s and 1980s, Article 32 has also provided a form of legal mechanism to seek remedy for systemic violations of rights that impact large groups of individuals, or the public as a whole.

- Environmental degradation

- Bonded labour

- Custodial violence

- Representation of socially and politically marginalized communities

The use of Public Interest Litigation has provided the Court a focal point to hear grievances regarding these issues, helping to solidify the notion of the Supreme Court as custodian of democracy (Chanda, 2012).

Conclusion

Article 32 and Article 226 of the Constitution of India establish a sophisticated, interrelated regime of constitutional remedies that are critical to the democracy of India. In contrast to mere procedural provisions, they demonstrate faith in the relevance of remedies to rights. Through them, collectively, Fundamental Rights are enforced and access to justice is made easy.

Article 32: The Heart and Soul of the Constitution

Article 32 stands out as an independent Fundamental Right. It referred to it as the “heart and soul” of the Constitution, revealing its significance. Any person whose Fundamental Rights are infringed can directly approach the Supreme Court without first exhausting lower remedies.

The Court can grant five kinds of writs:

- Habeas Corpus

- Mandamus

- Prohibition

- Certiorari

- Quo Warranto

This makes the guarantee effective. Decisions in cases such as Maneka Gandhi and Bandhua Mukti Morcha have expanded the rights which are enforceable under Article 32. The Supreme Court is able to address individual grievances and issues at large by means of Public Interest Litigation.

Yet the Court has emphasized that such jurisdiction exists solely for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights and not for ordinary statutory or contractual disputes, which serves to maintain the remedy constitutional.

Article 226: Wider and More Elastic Jurisdiction

Conversely, Article 226 is not a Fundamental Right; it is a constitutional power accorded to all High Courts. Its ambit is wider and more elastic. High Courts can issue the same five writs to uphold Fundamental Rights and other purposes, such as statutory, common-law, and some contractual rights.

This increased scope enables citizens to challenge administrative action, enforce observance of natural justice, and safeguard legal rights despite the absence of a Fundamental Right.

Territorial jurisdiction, as established in decisions such as Election Commission v. Saka Venkata Rao and Navinchandra Majithia, means High Courts can exercise power whenever a material portion of the cause of action takes place within their jurisdiction, making it easier for people to access justice.

Complementary Nature of Articles 32 and 226

Judicial precedent indicates that these two Articles complement each other but do not conflict with each other. The Supreme Court, in L. Chandra Kumar, held that the judicial review under Articles 32 and 226 forms part of the basic structure of the Constitution and cannot be lightly changed or overridden.

While overlapping jurisdictions may result in “forum shopping,” the Constitution is so framed that no illegality on the part of the legislature, the executive, or the lower judiciary goes unpunished.

Institutional Roles of Courts

| High Courts | Supreme Court |

|---|---|

| Act as the first constitutional watchdogs in the states and grant more expeditious relief, reducing the workload of the Supreme Court. | Remains the ultimate guardian of Fundamental Rights and the final interpreter of the Constitution. |

Implications for Indian Democracy

This two-tier system has profound implications for democracy. It decentralizes constitutional justice, bringing remedies within reach of ordinary citizens and bolstering the supremacy of the Constitution over all State branches.

Article 32 provides that basic freedoms are not made nugatory by executive or legislative measures, while Article 226 ensures judicial protection even for non-basic legal interests.

Together, they form a seamless line of responsibility, maintaining the rule of law and promoting the vision of India as a “living Constitution” in which rights are actual, actionable, and consequential.

By creating both central and provincial channels of constitutional remedy, the framers constructed not only an apparatus of enforcement but a base for Indian democracy itself.