Introduction

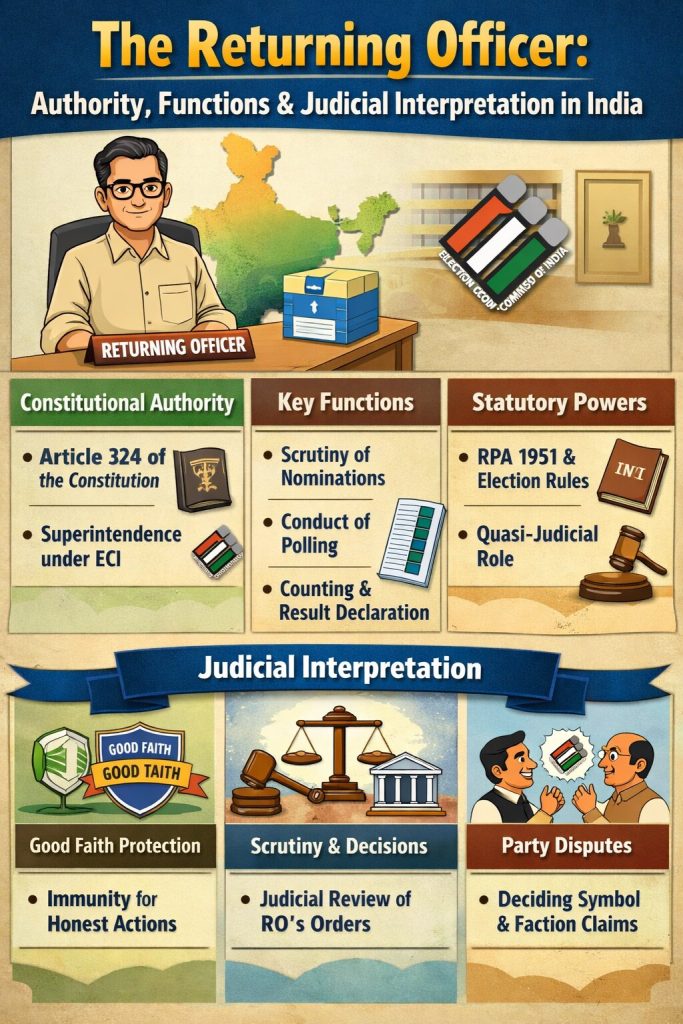

The Returning Officer (RO) in India derives authority from the Constitution of India and the statutory framework governing elections. The office is not created by a single exhaustive provision but emerges from a combination of constitutional mandates, parliamentary enactments, and subordinate rules. Anchored primarily in Article 324 of the Constitution and the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA, 1951), the RO functions as the cornerstone of electoral administration at the constituency level, responsible for conducting elections in a free, fair, and lawful manner.

The role encompasses wide-ranging administrative and quasi-judicial powers relating to nominations, scrutiny, polling, counting, and declaration of results, while ensuring compliance with electoral laws and directions of the Election Commission of India (ECI). Judicial interpretation has further delineated the scope, limits, and accountability of the RO, reinforcing the office’s central importance in upholding the integrity of India’s democratic process.

Constitutional Provision

Article 324 of the Constitution of India

This foundational provision vests the superintendence, direction, and control of the preparation of electoral rolls and the conduct of all elections (to Parliament, State Legislatures, President, and Vice-President) in the ECI. The ECI appoints or nominates Returning Officers (and Assistant Returning Officers) under powers derived from this Article, often in consultation with state governments. The RO acts as the ECI’s delegate at the constituency level, overseeing the entire electoral process in one or more constituencies.

Key Sections under the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA, 1951)

Section 21: Appointment of Returning Officers — The ECI may appoint one or more ROs for a constituency (or constituencies) and Assistant Returning Officers to assist.

Section 22: Assistant Returning Officers (performing functions of RO) — The ECI may appoint assistants who can perform functions authorized by the RO or ECI (e.g., scrutiny or segment-wise polling).

Section 23: Returning Officer to include Assistant Returning Officers performing functions — Clarifies that references to the RO include assistants when performing delegated functions.

Section 31: Public notice of election — The RO publishes the notice (in Form 1 under the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961) on the date specified in the ECI’s notification.

Section 33: Presentation of nomination papers — Nomination papers are presented to the RO (or authorized person), who receives them, checks deposits, and administers oaths/affirmations.

Section 36: Scrutiny of nominations — A critical quasi-judicial function; the RO scrutinizes papers, hears objections, and decides on acceptance/rejection (recording brief reasons for rejections). Rejections are limited to substantial defects; curable/minor ones are not grounds.

Section 37: Withdrawal of candidature — The RO receives and notes withdrawal notices.

Section 38: Publication of list of contesting candidates (including allotment of election symbols) — The RO publishes the list (in Form 7A) after withdrawals, allotting symbols as per the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, and ECI directions.

Various sections in Part V (Conduct of Elections, Sections 47–78): The RO oversees polling arrangements (e.g., polling stations, presiding officers), counting, and declaration of results.

Section 64: Counting of votes — The RO supervises counting.

Section 66: Declaration of result — The RO declares the elected candidate after counting.

Section 134: Breaches of official duty in connection with elections — Applies to the RO; imposes penalties for breaches without reasonable cause, while protecting good-faith acts from civil suits.

Key Rules under the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961

These Rules, framed under the Representation of the People Act, 1951, lay down detailed procedural guidelines for the conduct of elections.

Rule 3: Public notice of intended election (Form 1) — issued by the Returning Officer.

Rules 4–10: Provisions relating to nominations, including presentation of nomination papers, security deposits, publication of the list of nominations, withdrawal of candidature (Form 5), and preparation and publication of the list of contesting candidates (Forms 7A/7B).

Rule 11: Scrutiny of nominations — conducted by the Returning Officer.

Rule 10: Preparation and publication of the list of contesting candidates by the Returning Officer after scrutiny and withdrawals (Form 7A or 7B, as applicable).

Rules 28–49: Provisions relating to polling, including the fixing of polling stations, appointment of presiding and polling officers, use of marked copies of electoral rolls, voting procedures through ballot papers/EVMs, and maintenance of secrecy of voting.

Rules 50–66 (and allied provisions): Counting of votes, sealing and custody of EVMs/ballot boxes, declaration of result, and safe custody of election records.

Other provisions: Rules relating to postal ballots, service voters, election duty votes, and special voting procedures, many of which involve the Returning Officer.

Additional Frameworks

Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968: Regulates the reservation and allotment of election symbols by the Election Commission of India, with the Returning Officer implementing symbol choice and allotment at the constituency level strictly in accordance with ECI directions, supported procedurally by Rules 5 and 10(4) of the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961.

Handbooks and Instructions from ECI: Practical guidance (e.g., Handbook for Returning Officers) supplements statutes with checklists, timelines, and best practices.

Model Code of Conduct: Enforced at the constituency level by the Returning Officer under the overall superintendence, direction, and control of the Election Commission of India in terms of Article 324 of the Constitution.

In summary, the Returning Officer’s authority flows from Article 324 (constitutional superintendence of elections by the ECI) and is operationalized primarily through Sections 21–23, 31, 33, 36, 37, 38, 64, 66, and 134 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, supplemented by detailed procedures under the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961. The Returning Officer functions as the key statutory pivot for constituency-level election administration, exercising quasi-judicial powers—particularly during the scrutiny of nominations—and enjoying statutory protection for actions taken in good faith, subject to post-election judicial scrutiny through election petitions.

Judicial Nature of the Returning Officer’s Functions

The Supreme Court has consistently held that certain functions of the Returning Officer—particularly the scrutiny of nomination papers—are quasi-judicial in character. While the RO is not a court, this role demands the application of legal standards and adherence to principles of natural justice. In Virindar Kumar Satyawadi v. State of Punjab (AIR 1956 SC 153) and subsequent rulings, the Court has emphasized that the RO must act with fairness, objectivity, and in strict accordance with law when scrutinizing nominations. The scrutiny process requires reasoned decision-making, especially in cases of rejection, to uphold electoral integrity.

Acceptance and Rejection of Nomination Papers

Improper acceptance or rejection of a nomination constitutes a grave electoral infirmity. In Shiv Kirpal Singh v. V.V. Giri ((1970) 2 SCC 567), the Supreme Court ruled that an erroneous rejection of nomination papers can vitiate the election if it materially affects the result. The Court stressed: “The right to contest an election, though statutory, cannot be defeated by an arbitrary or mechanical exercise of power by the Returning Officer.”

Similarly, in Brundaban Nayak v. Election Commission of India (AIR 1965 SC 1892), the Court cautioned against a hyper-technical approach during scrutiny, particularly for curable defects, underscoring the need for substantive justice over procedural rigidity.

Limited Judicial Interference During the Electoral Process

A foundational principle is the bar on judicial interference during ongoing elections. In the landmark case of N.P. Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer, Namakkal (AIR 1952 SC 64), the Supreme Court held that challenges to the RO’s actions—such as acceptance or rejection of nominations—cannot be entertained mid-process and must await an election petition after completion. The Court famously observed: “The law of elections in this country does not contemplate that there should be two attacks on election proceedings—one while they are going on and another after they have been completed.” This doctrine safeguards the seamless conduct of elections and shields the RO from premature litigation.

Declaration of Results and Finality

The RO’s declaration of results marks the culmination of the electoral process. In Mohinder Singh Gill v. Chief Election Commissioner ((1978) 1 SCC 405), while examining the ECI’s broader powers, the Supreme Court affirmed the RO’s statutory authority at the constituency level, noting: “The Returning Officer is the statutory pivot of the election in a constituency, whose actions are final for the purpose of the poll, subject only to election petitions.” This reinforces the RO’s operational autonomy and responsibility.

Good Faith Protection and Accountability

Courts recognize the intense pressure and time-bound nature of the RO’s duties. In Hari Vishnu Kamath v. Ahmad Ishaque (AIR 1955 SC 233), the Supreme Court held that errors committed in good faith do not automatically invalidate an election unless they materially affect the result. The Court observed: “Election law does not envisage the setting aside of elections for mere technical errors or omissions which do not go to the root of the matter.” This balanced approach protects functionality while ensuring accountability.

Drawbacks of the Returning Officer

Despite serving as a pivotal figure in ensuring the smooth conduct of elections, the Returning Officer (RO) encounters several inherent limitations that can compromise the efficiency, impartiality, and robustness of election administration.

- Overburdened Workload and Time Constraints — The RO is typically a serving government administrative officer (e.g., District Collector/ Additional District Collector/ Sub-divisional Magistrate Magistrate or equivalent) who juggles multiple non-election duties. This dual responsibility leads to an intense workload, acute time pressure, and significant operational stress, especially during the compressed election schedule involving nomination scrutiny, polling arrangements, counting, and result declaration.

- Limited Institutional Independence — As part of the executive branch hierarchy, the RO lacks full institutional autonomy from the government. This structural position can foster perceptions of bias or executive influence, particularly in politically charged or sensitive constituencies, even when the RO acts in good faith under Election Commission directives.

- Challenges in Quasi-Judicial Decision-Making — Although equipped with quasi-judicial powers—most notably during the scrutiny of nominations under Section 36 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951—the RO must render legally binding decisions within extremely tight statutory timelines. The scope for in-depth inquiry is limited to a summary process, heightening the risk of procedural errors, improper acceptances or rejections, and subsequent election petitions or litigation that may challenge results.

- Restricted Discretion Due to Centralized Instructions — The RO operates under strict, detailed guidelines and instructions from the Election Commission of India. While this promotes uniformity, it can curtail necessary situational discretion in handling unique local contingencies, potentially leading to rigid application of rules that may not fully address ground realities.

- Variable Legal Expertise and Training Gaps — Not all ROs possess specialized legal training or extensive prior experience in electoral law. Variations in competence can result in inadvertent lapses during complex tasks like nomination scrutiny (e.g., assessing “defects of substantial character”), symbol allotment, or managing objections, thereby exposing decisions to judicial scrutiny and potential invalidation.

- Pressure to Reject Opposition Nominations

Returning Officers often face intense political pressure from ruling party affiliates to reject nomination papers of opposition candidates on technical or flimsy grounds. This undermines electoral integrity, erodes public trust, and risks post-election litigation, highlighting the RO’s vulnerable position despite quasi-judicial powers.

- Bias in Enforcement of Model Code of Conduct

The Model Code of Conduct is often enforced unevenly, with stricter action against opposition leaders for alleged violations while ruling party infractions—such as hate speech, misuse of government machinery, or inducements—receive lenient or delayed responses, fostering perceptions of partisan bias by election authorities.

- Bias in Granting Campaign Permissions

Returning Officers may be perceived as biased when permissions for public meetings, rallies, or campaign activities are granted selectively or with delay, favouring ruling parties while imposing restrictive conditions on opposition candidates. Such unequal application of rules undermines the level playing field mandated by the Model Code of Conduct.

- Bias in Lodging and Processing Complaints

Bias may arise when complaints against ruling party candidates are ignored, delayed, or diluted, while those against opposition candidates are acted upon swiftly. Selective registration, inquiry, or forwarding of complaints undermines neutrality, weakens enforcement of the Model Code of Conduct, and erodes public confidence in the fairness of election administration.

These limitations underscore the need for reforms such as dedicated election cadres, enhanced training, greater safeguards for independence, or expanded support mechanisms to strengthen the RO’s effectiveness while upholding the integrity of India’s electoral process. Overall, while the RO remains indispensable, these constraints highlight systemic pressures on frontline election administrators in the world’s largest democracy.

Conclusion

The Returning Officer occupies a pivotal position in India’s electoral architecture, translating the constitutional mandate of free and fair elections into operational reality at the constituency level. Drawing authority from Article 324 of the Constitution and a comprehensive statutory framework under the Representation of the People Act, 1951 and the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961, the RO performs a delicate blend of administrative and quasi-judicial functions that directly influence the legitimacy of the electoral outcome. Judicial interpretation has consistently reinforced both the finality and accountability of the RO’s actions—shielding good-faith decisions from undue interference while permitting post-election scrutiny through election petitions to safeguard democratic integrity.

At the same time, structural and practical constraints, including workload pressures, limited institutional independence, and the complexity of legal decision-making under strict timelines, expose the vulnerabilities of the office. Taken together, the analysis underscores that while the Returning Officer is indispensable as the statutory pivot of constituency-level election administration, strengthening institutional support, training, and autonomy is essential to further reinforce public confidence in India’s electoral democracy.