Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) are among the deadliest threats faced by security forces because they are designed to exploit human behavior rather than technology alone. Even when made from simple materials, IEDs take advantage of curiosity that draws personnel closer, haste driven by operational pressure, overconfidence built from past experience, or the temptation to ignore standard operating procedures. These devices are deliberately placed to punish small mistakes, turning a momentary lapse into a fatal outcome. This makes discipline, patience, and strict adherence to procedure essential in every IED-related situation.

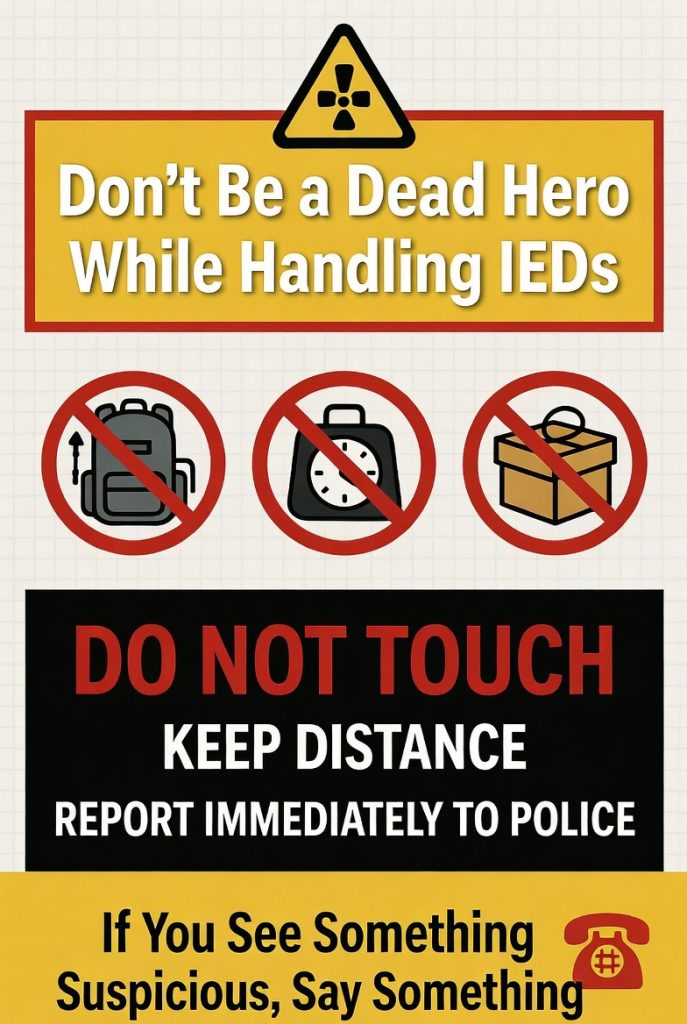

The warning “Don’t be a dead hero” is therefore not a slogan meant to discourage courage, but a professional principle meant to protect lives. For soldiers, police officers, and bomb disposal experts, real courage lies in restraint, not reckless action. Following established protocols, using distance and technology, and taking the necessary time to assess threats saves lives and preserves operational capability. In counter-IED operations, survival is the true measure of success, because staying alive ensures experience, skills, and vigilance remain available for future missions.

The Illusion of Experience and the Cost of Complacency

One of the biggest dangers around IEDs is overconfidence caused by familiarity. After many patrols or defusal missions, experienced personnel may start relying on instinct instead of procedures, cut corners to save time, or treat a suspicious object as routine. This is exactly what IEDs are designed to exploit. Even highly trained Bomb Disposal Squad (BDS) experts have been killed because of a single mistake—getting too close without full protection, missing booby traps, or ignoring the risk of secondary devices.

This risk is well documented. In places like Iraq, Afghanistan, and India’s Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) areas, studies show that nearly 30–40% of IED casualties among experienced personnel are due to skipped procedures, not lack of training. Experience only reduces danger when it is matched with strict discipline. Otherwise, it becomes a hidden risk. As experts often say, a bomb does not care how experienced you are—it only reacts to what you do.

Case Examples: When Negligence Turned Fatal

Real incidents clearly show how small mistakes and overconfidence can turn manageable IED situations into deadly disasters. These are not rare events—they follow a repeated pattern.

- Central India (LWE area, 2019): In Gadchiroli, 15 elite QAT commandos were killed when Maoists triggered IEDs during a search operation. Familiarity with the area, fatigue, and poor reconnaissance led to pressure-plate devices being missed along escape routes. Past successes created a false sense of safety.

- Jammu & Kashmir (2023): Near the Line of Control, an IED was declared neutralized after partial defusal. Secondary devices were not checked properly. The IED later exploded during routine movement, killing three personnel and injuring others.

- Delhi-NCR (2025): In a crowded market, first responders chose close inspection instead of evacuation and robotic handling. The VBIED detonated, killing one officer and injuring four. Speed was chosen over safety.

- Iraq (2021): An Iraqi EOD team rushed the removal of an artillery shell IED without checking for anti-tamper devices. The explosion killed two technicians and injured three, showing how skipping steps can be fatal even for trained teams.

- Afghanistan (2007–2014): Thousands of IED casualties occurred due to repeated use of the same routes and relaxed threat assessment. In one case, a “cleared” culvert contained a secondary device that killed four EOD personnel.

- The most prominent “Barikul incident” in the context of Maoist/IED threats in West Bengal refers to the July 9, 2005, killing of Prabal Sengupta, the Officer-in-Charge (OC) of Barikul Police Station in Bankura district.

Maoists first gunned down two CPI(M) leaders (Raghunath Murmu and Bablu Mudi) in Majhgeria village. They left behind a booby-trapped bag containing explosives as a deadly lure. Sengupta, responding to the scene around 11 PM with a small team, attempted to examine/open the suspicious bag—likely assuming it held evidence or weapons—triggering the device. The explosion killed him instantly and injured others.

This case exemplifies the “Don’t Be a Dead Hero” principle: an experienced officer’s fatal lapse in manually handling a potential IED (booby trap) without remote tools, full standoff, or protocol-driven caution, despite the known Maoist tactic of secondary/anti-handling devices to target responders.

These cases underline a hard truth: IEDs punish shortcuts. When discipline fades, even the best training cannot prevent loss of life.

Heroism vs. Professionalism: Redefining Valour in the Face of Fire

In counter-IED work, true heroism is not about dramatic acts or risky bravery, but about calm discipline and controlled action. Rushing toward a device without full preparation, trying quick fixes under pressure, or giving in to demands from seniors or anxious civilians weakens professional standards.

Around the world, bomb disposal doctrines—from the U.S. Joint Improvised-Threat Defeat Organization to India’s National Bomb Data Centre—agree on three basic rules that save lives: distance, time, and protection. Keep maximum distance by using robots or drones. Take enough time and never rush, because careful work is more important than speed. Always use proper shielding, including blast suits, armour, and barriers.

A hard lesson came from the 2019 South Los Angeles fireworks explosion, when an LAPD bomb squad vehicle failed during a controlled blast. Thirty-one people were injured due to wrong safety assumptions. Real courage is shown by the technician who stops, reassesses, and refuses to hurry, denying the device its chance to win.

Best Practices: Building Strong Protection Against IEDs

To reduce mistakes and save lives, counter-IED procedures must go beyond basic rules and adapt to new threats with the help of technology and training. Key best practices include:

- Robotic and Remote Handling: Use unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), such as TALON or DRDO-developed robots, for checking and disrupting devices first. This keeps personnel at safe distances, often more than 100 meters away.

- Layered Threat Checks: Combine multiple tools like ground-penetrating radar, chemical sensors, and AI-based detection systems to find hidden or secondary devices. This greatly reduces missed threats.

- Psychological Training: Include special drills that target overconfidence, especially in familiar situations. Training should reinforce the rule: never assume—always verify.

- Post-Incident Reviews: Conduct mandatory debriefs after every incident, focusing on human factors like fatigue or judgment errors, not just technical issues. This helps teams learn and improve together.

Following these practices is not optional. It is the difference between staying effective in the field and suffering avoidable loss.

Systemic Factors That Contribute to Fatal Errors

Sadly, many deaths from IEDs are not caused by individual carelessness but by system-level failures: irregular refresher training that weakens skills, extreme fatigue from repeated deployments in dangerous areas, poor coordination between intelligence and field teams, and constant pressure to reopen roads or markets for political or economic reasons. In West Africa, IED attacks killed more than 100 people in Nigeria in 2023, made worse by weak funding and limited counter-terror resources. Worldwide, the UN estimates that IEDs account for about 40% of casualties in asymmetric conflicts, with poor systems increasing the damage. Preventing this requires broad reform: fixed rotation limits, joint intelligence centres, and leaders who treat every avoidable death as a failure of command.

The Core Message: Survival as Strategy

An IED neutralized at the cost of a defender’s life is not a victory—it is a costly loss that benefits the enemy. The goal is not reckless heroism, but denying adversaries casualties, fear, and propaganda for recruitment. Every fallen bomb technician weakens morale, raises training costs, and encourages militants, as seen after 2021 when Taliban IED attacks resurged, causing over 2,000 coalition casualties between 2001 and 2021. Protecting lives honours the fallen by ensuring their skills and experience live on.

Conclusion: Humility in the Shadow of the Blast

“Don’t be a dead hero” is written not with ink but in the scars of survivors and the silence of those lost—a clear warning to stay humble, remain patient, and follow standard operating procedures like a lifeline. In the harsh math of IEDs, the safest choice is often the slower one: stop, breathe, reassess calmly, and use distance, information, and tools instead of courage. Survival is not the opposite of bravery; it is its highest form, a duty that protects tomorrow’s protectors. In a world where every wire hides risk, let this rule be the shield that stands firm and outlasts fear, chaos, and death.