India is among the most disaster‑prone nations globally. Nearly 60% of its landmass is vulnerable to earthquakes, 12% to floods, and 68% to droughts. Recognizing this, Parliament enacted the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (DMA), establishing a three‑tier institutional framework: the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), State Disaster Management Authorities (SDMAs), and District Disaster Management Authorities (DDMAs).

Yet, despite this statutory architecture, district‑level implementation remains the weakest link. This article examines the common problems in disaster management at the district level, situating them within the statutory framework and judicial pronouncements, while offering recommendations for reform.

Statutory Framework

The DMA 2005 provides the legal foundation for disaster management in India.

- Section 25: Establishes DDMAs, chaired by the District Magistrate/Collector.

- Section 31: Mandates preparation of District Disaster Management Plans (DDMPs).

- Section 33: Empowers DDMAs to coordinate and monitor disaster preparedness and response.

- Section 34: Grants powers to requisition resources, control traffic, and order evacuations.

Despite these provisions, implementation gaps persist, undermining the Act’s objectives.

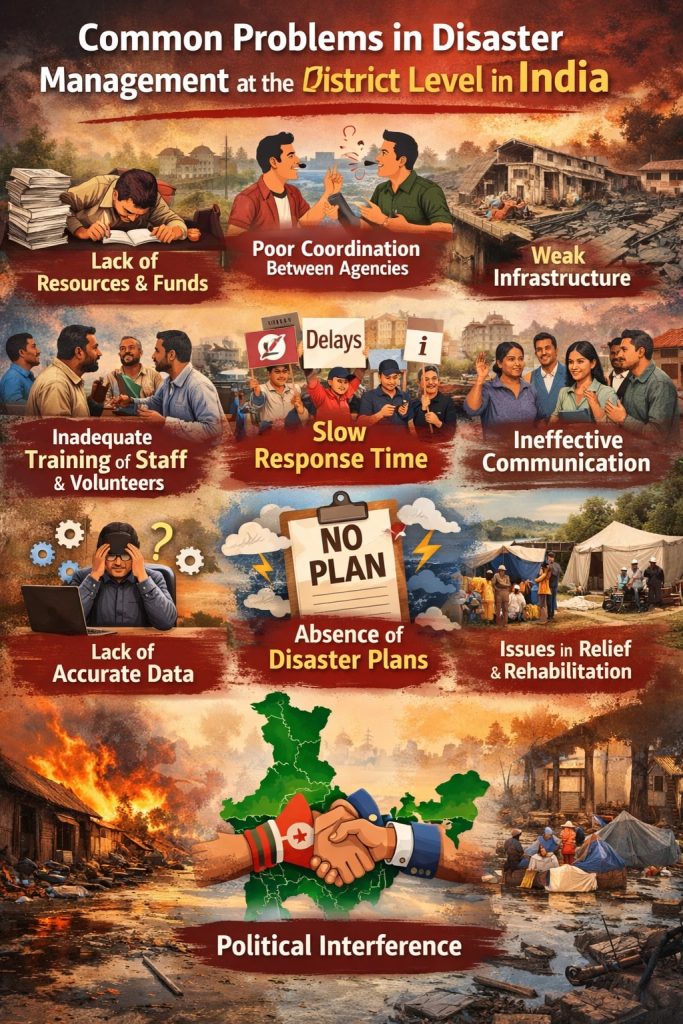

Common Problems

- Institutional and Policy Gaps

- DDMPs often remain outdated or perfunctory.

- Overlapping responsibilities between district departments create confusion.

- Accountability mechanisms under Section 33 are weak.

Coordination Failures

- Poor inter‑departmental coordination delays relief.

- Weak integration with SDMAs and NDMA.

- Bureaucratic red tape hampers rapid decision‑making.

Resource Constraints

- Lack of dedicated district‑level disaster funds.

- Shortage of trained personnel for search and rescue.

- Inadequate equipment and communication tools.

Infrastructure Deficiencies

- Poor road connectivity delays relief.

- District hospitals lack surge capacity.

- Communication breakdowns during disasters.

Community Participation Issues

- Low awareness of evacuation routes and shelters.

- Rarely conducted disaster drills.

- Vulnerable groups (women, children, elderly, disabled) often excluded.

- Climate Change and Urbanization Pressures

- Urban flooding due to unplanned growth.

- Encroachment on wetlands and forests.

- Increasing frequency of cyclones and heatwaves.

- Monitoring and Evaluation Weaknesses

- Lack of district‑level disaster risk databases.

- Poor early warning dissemination.

- Absence of post‑disaster reviews.

- Political and Administrative Challenges

- Relief prioritized over mitigation.

- Politicization of relief distribution.

- Frequent transfers of district officials disrupt continuity.

Judicial Perspectives

Indian courts have repeatedly emphasized the constitutional duty to protect life under Article 21 in disaster contexts:

- Charan Lal Sahu v. Union of India, (1990) 1 SCC 613 – Supreme Court underscored the State’s duty to protect citizens in the aftermath of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy.

- C. Mehta v. Union of India, (1987) 1 SCC 395 – Introduced the principle of absolute liability for hazardous industries, relevant for district‑level disaster preparedness.

- Gaurav Kumar Bansal v. Union of India, (2014) 6 SCC 321 – Court directed NDMA to frame guidelines for disaster relief, highlighting accountability gaps.

These cases demonstrate that district authorities cannot shirk responsibility, as disaster management is integral to the right to life.

Recommendations

- Strengthen DDMPs: Regular updates and integration with state/national plans.

- Dedicated Funds: Establish district disaster funds for immediate mobilization.

- Capacity Building: Training for officials, volunteers, and communities.

- Infrastructure Investment: Roads, health facilities, and communication systems.

- Community Engagement: Awareness campaigns, inclusion of vulnerable groups.

- Technology Integration: GIS, mobile apps, drones for early warning and relief.

- Accountability: Clear delineation of roles under Sections 33–34, DMA 2005.

Comparative Insights

- Japan: Localized Preparedness and Community Integration

Japan, one of the most disaster‑prepared nations, offers valuable lessons:

- Legal Framework: The Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act (1961) mandates local governments to prepare disaster management plans.

- Community Participation: Local volunteer fire corps and neighborhood associations are deeply integrated into disaster response.

- Technology Use: Japan employs advanced early warning systems for earthquakes and tsunamis, disseminated directly to local authorities and citizens.

- Case Study: During the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, local governments coordinated evacuation and relief despite massive infrastructural damage, demonstrating resilience through community‑based preparedness.

Lesson for India: District authorities must move beyond bureaucratic structures to embed community participation and technology integration into disaster planning. However, the 2011 Japan earthquake case highlights community resilience effectively, though it also exposed some initial coordination issues.

- United States: Federal‑Local Coordination through FEMA

The U.S. model emphasizes coordination between federal, state, and local agencies:

- Legal Framework: The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (1988) empowers the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support local governments.

- Incident Command System (ICS): Standardized command structures ensure clarity of roles during emergencies.

- Funding Mechanisms: FEMA provides pre‑disaster mitigation grants and post‑disaster relief funds directly to local governments.

- Case Study: Hurricane Katrina (2005) exposed failures in coordination, but subsequent reforms strengthened local preparedness through FEMA’s National Response Framework.

Lesson for India: District Disaster Management Authorities (DDMAs) require dedicated funding and standardized command structures to avoid confusion and delays.

- Comparative Table

|

Country |

Local Authority Role |

Community Involvement |

Funding |

Technology Use |

Lessons for India |

|

India |

DDMA under DMA 2005 |

Limited, ad‑hoc |

No dedicated funds |

Weak early warning |

Strengthen DDMPs, funds, accountability |

|

Japan |

Local governments under Disaster Act |

Strong volunteer corps |

Local + national |

Advanced earthquake/tsunami alerts |

Embed community + tech |

|

U.S. |

Local govts under FEMA framework |

Moderate, structured |

Federal grants |

ICS + digital alerts |

Standardize command + funding |

Integrating Comparative Lessons into Indian Context

- Community‑Based Models (Japan): India should institutionalize village‑level disaster committees under DDMPs.

- Funding Mechanisms (U.S.): Dedicated district disaster funds, akin to FEMA grants, must be legislated.

- Technology Integration (Japan/U.S.): GIS mapping, mobile alerts, and real‑time dashboards should be mandatory at district headquarters.

- Standardized Command (U.S.): Adoption of an Incident Command System under Section 33, DMA 2005 would clarify roles and reduce bureaucratic delays.

Conclusion

A comparative analysis underscores that India’s district‑level disaster management continues to lag behind global best practices. Japan illustrates the transformative role of community integration, while the United States highlights the necessity of dedicated funding and standardized command structures. Incorporating these lessons into India’s statutory framework would not only enhance resilience but also fulfill the constitutional mandate under Article 21 to protect life and personal liberty.

Despite the robust architecture of the Disaster Management Act, 2005, district‑level implementation remains uneven, plagued by institutional gaps, poor coordination, resource shortages, and weak community engagement. Judicial pronouncements have consistently reinforced the constitutional imperative of disaster preparedness, reminding authorities that disaster management is inseparable from the right to life. Strengthening district capacity—through clearer accountability, adequate resources, and meaningful community participation—is therefore essential to safeguard lives and build resilience in India’s disaster‑prone regions.