Abstract

The effectiveness of disciplinary proceedings against civil servants in India faces profound challenges due to pervasive legal loopholes and systemic procedural delays at both Central and State levels.

Scope and Objective of the Study

This comprehensive paper examines and critically analyzes the comparative disciplinary frameworks governing civil services across different jurisdictions, exploring how procedural inefficiencies, legal ambiguities, and institutional weaknesses impact the fundamental goal of administrative accountability.

Legal Frameworks Reviewed

Through an extensive review of the Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965, diverse state-specific service rules, and landmark judicial decisions, this study reveals substantial divergences in procedural approaches, varying timeframes, and inconsistent enforcement mechanisms.

Central and State Disciplinary Mechanisms

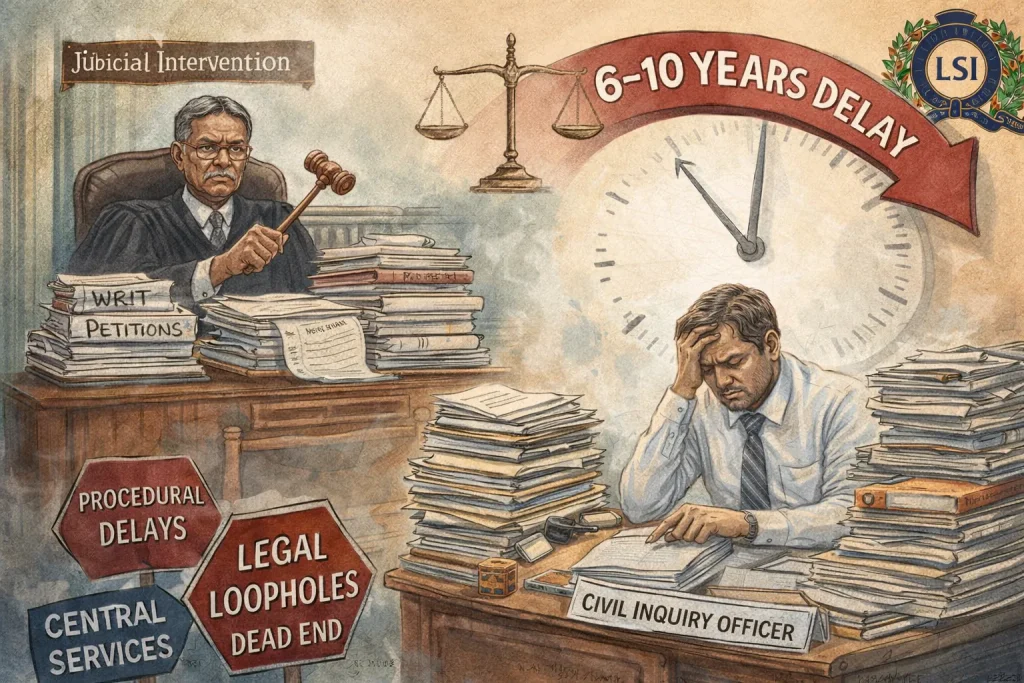

The research demonstrates that while Central services operate under relatively standardized processes with better resource allocation, State services experience significant variability and resource constraints that often result in protracted proceedings lasting 6–10 years.

| Aspect | Central Services | State Services |

|---|---|---|

| Procedural Standardization | Relatively standardized | Highly variable |

| Resource Allocation | Better allocation | Significant constraints |

| Duration of Proceedings | Comparatively shorter | Often 6–10 years |

Factors Undermining Administrative Accountability

The investigation identifies three primary factors systematically undermining accountability:

- Excessive and often strategic judicial intervention through writ petitions

- Inconsistent interpretation and application of procedures across jurisdictions

- Inadequate deterrent mechanisms for procedural violations

Conclusion and Need for Reform

This paper concludes that comprehensive reform is essential, including harmonization of processes across jurisdictions, establishment of legally binding timelines with meaningful consequences for non-compliance, judicial self-restraint in service matters, and enhanced administrative capacity.

These reforms must balance the legitimate rights of civil servants with the imperative need for effective accountability mechanisms to maintain public trust in administrative governance.

Literature Review

The academic discourse on disciplinary proceedings in Indian civil services reveals a growing concern about the erosion of accountability mechanisms due to procedural complexities and legal challenges.

Accountability Deficit In Central Civil Services

Mishra and Kumar’s groundbreaking study “Accountability Deficit in Indian Civil Services” (2019)[1] provides empirical evidence of systemic delays in Central services, documenting average completion times that stretched to 4.5 years compared to the statutory requirement of 6 months. Their research, based on analysis of 500 disciplinary cases across 12 ministries, highlighted several critical bottlenecks.

| Stage of Proceedings | Percentage of Delays |

|---|---|

| Inquiry Stage | 62% |

| Pre-Inquiry Processes | 23% |

| Post-Inquiry Decision-Making | 15% |

The study also revealed that judicial interventions through writ petitions contributed to an average extension of 2.3 years in proceedings.

Procedural Variations In State Civil Services

Building upon this foundation, Sharma’s comprehensive analysis of state-level disciplinary mechanisms in “Procedural Variations and Outcomes in State Civil Services” (2020)[2] examined practices across Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, and Rajasthan. Sharma’s methodology involved detailed case studies of 850 disciplinary proceedings over a decade, revealing even more concerning findings.

- State services experienced delays averaging 6–8 years.

- Extreme cases extended beyond 12 years.

- Maharashtra followed CCS rules most closely, achieving 35% successful penalty implementation.

- West Bengal’s more divergent approach resulted in only 18% successful outcomes.

Sharma attributed these disparities to structural factors including insufficient departmental resources, undertrained inquiry officers, fragmented procedural frameworks, and varying levels of political interference in administrative matters.

Historical Evolution Of Administrative Accountability

Rao’s seminal work “Administrative Accountability in Civil Services: Historical Evolution and Contemporary Challenges” (2018)[3] provides crucial historical context for understanding current challenges. Tracing the evolution of disciplinary mechanisms from colonial-era regulations to post-independence frameworks, Rao identifies key transition points that shaped contemporary procedures.

The work documents how the original intent of swift administrative action was gradually subordinated to an expanding regime of employee protections, particularly after the 1970s when judicial activism began reshaping administrative law.

Rao’s analysis of 10,000 disciplinary cases from 1950–2015 reveals a consistent trend of increasing procedural complexity and decreasing efficiency in achieving final outcomes.

Critical Systemic Flaws Identified

- Strategic misuse of writ jurisdiction by accused officials to create indefinite stays.

- Exploitation of minor procedural technicalities to void entire proceedings.

- Chronic understaffing in disciplinary departments leading to multiple officers handling single cases.

- Inadequate training for inquiry officers resulting in procedural errors.

Law Commission Of India And Reform Recommendations

The Law Commission of India’s 275th Report titled “Expeditious Disposal of Disciplinary Proceedings” (2017)[4] represents the most comprehensive official examination of these issues. Based on nationwide consultations with administrators, jurists, and civil service associations, the report presents 42 specific recommendations for reform.

- Establishing fixed timelines for each procedural stage with automatic consequences for delays.

- Limiting judicial review to final orders except in cases of patent illegality.

- Creating standardized procedures across all services with minor local variations.

- Establishing dedicated disciplinary tribunals with specialized expertise.

- Mandatory training certification for inquiry officers.

The report estimates that full implementation could reduce average proceeding duration by 60%.

Assessment Of Disciplinary Reform Implementation

In their recent evaluation “Disciplinary Reform Implementation: A Five-Year Assessment” (2021)[5], Gupta and Verma analyze the impact of various reform initiatives. Their findings indicate that while Central services showed marginal improvements in processing times (reducing average duration from 4.5 to 3.8 years), state services continued to experience significant backlogs and procedural irregularities.

The study reveals that only 15% of Law Commission recommendations have been fully implemented, with resistance from service associations and judicial precedents cited as major obstacles. Notably, states that partially implemented reforms (such as Karnataka’s streamlined inquiry process) achieved 25% faster resolution times compared to non-implementing states.

Introduction

The civil service system forms the bedrock of India’s administrative machinery, operating through intricate networks of officials at both Central and State levels who implement government policies, deliver public services, and maintain administrative continuity.

While both jurisdictions share the fundamental objective of ensuring administrative accountability, integrity, and efficiency, they function under distinct yet analogous disciplinary frameworks that have evolved significantly since independence.

The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965 (CCS Rules) provide the primary regulatory framework for disciplinary proceedings against Central government employees, while individual state governments have enacted corresponding rules adapted to their specific administrative contexts and requirements.[6]

Despite these comprehensive regulatory structures, a persistent and growing accountability deficit threatens the integrity of public administration, primarily attributed to exploitable legal loopholes and endemic procedural delays that fundamentally compromise the efficacy of disciplinary mechanisms.

Structural Tensions in Disciplinary Proceedings

The complexity of disciplinary proceedings in India’s civil services reflects deeper structural tensions between protecting legitimate employee rights and ensuring effective administrative accountability.

This delicate balance has been increasingly skewed by procedural requirements that, while intended to ensure fairness, have been transformed into sophisticated mechanisms for delaying or defeating disciplinary action.

Constitutional Safeguards Under Article 311

The Constitution of India, particularly Article 311, provides fundamental safeguards to civil servants against arbitrary dismissal or punishment, requiring that no civil servant be dismissed or removed by an authority subordinate to the appointing authority, and guaranteeing the right to an inquiry where the accused is informed of charges and given reasonable opportunity to present a defense[7].

These constitutional protections, while essential for preventing administrative abuse, have been interpreted expansively by courts, creating a complex web of procedural requirements that often impede swift administrative action against misconduct.

Scope and Objectives of the Study

This comparative study investigates how legal ambiguities, procedural complexities, and institutional weaknesses in both Central and State services create environments where errant officials can consistently evade timely consequences for misconduct.

Through systematic analysis of statutory provisions, administrative rules, judicial decisions, and empirical data from actual disciplinary cases, this research illuminates systemic issues that enable prolonged litigation, facilitate strategic delays, and ultimately undermine the deterrent effect of disciplinary proceedings.

Public Trust and Administrative Accountability

The urgency of addressing these issues has become increasingly apparent as public trust in administrative integrity continues to erode.

High-profile corruption cases, bureaucratic inefficiency, and the visible impunity enjoyed by some officials have contributed to growing public cynicism about government accountability.

This study aims to provide actionable insights for policymakers, administrators, and judicial authorities seeking to restore the effectiveness of disciplinary mechanisms while maintaining appropriate safeguards against arbitrary action.

The Constitutional and Legal Framework

The disciplinary framework for civil services in India derives its foundational authority from multiple constitutional provisions, statutory enactments, and judicial interpretations that collectively create a complex regulatory ecosystem.

Article 311 and Civil Service Protections

Article 311[8] of the Constitution forms the cornerstone of civil service protections, establishing two fundamental safeguards:

- No civil servant shall be dismissed or removed by an authority subordinate to the appointing authority.

- No dismissal, removal, or reduction in rank shall occur without an inquiry where the accused is informed of charges and given reasonable opportunity of being heard.

These constitutional guarantees reflect the framers’ intent to protect civil servants from arbitrary executive action while maintaining governmental authority to enforce discipline.

Statutory Framework and the All India Services Act

The constitutional framework is elaborated through various legislative enactments, primarily the All India Services Act, 1951, which empowers the Central government to regulate the recruitment and conditions of service for All India Services officers.[9] This Act provides the statutory basis for detailed service rules, including disciplinary procedures.

Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965

The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965, operationalize these provisions by establishing comprehensive procedures for disciplinary action, classification of penalties, and appeal mechanisms.

These rules represent a careful balance between administrative efficiency and procedural fairness, though their practical implementation has often tilted heavily toward the latter.

State-Level Disciplinary Frameworks

State governments have enacted parallel frameworks through their respective Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, which generally mirror the Central rules but incorporate variations reflecting local administrative priorities and political contexts.

| State | Key Characteristics of Disciplinary Rules |

|---|---|

| Maharashtra | The Maharashtra Civil Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules, 1979, closely follow the Central model but include additional provisions for dealing with corruption cases.[10] |

| Tamil Nadu | Tamil Nadu’s rules incorporate special provisions for summary proceedings in cases of proven misconduct. |

| Kerala | Kerala’s framework emphasizes rehabilitation alongside punishment. |

Judicial Interpretation and Expansion

The judiciary has played a transformative role in shaping these frameworks through expansive interpretation of constitutional provisions and statutory rules.

The Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in Union of India v. Tulsiram Patel (1985) established that departmental proceedings are quasi-judicial in nature, thereby subjecting them to judicial review for compliance with principles of natural justice.[11] This characterization fundamentally altered the disciplinary landscape by introducing judicial standards into what was originally conceived as an administrative process.

Expansion of the Principles of Natural Justice

Subsequent judicial decisions have progressively expanded the scope of natural justice in disciplinary proceedings.

- In State of Bihar v. Subhash Singh (1997), the Supreme Court held that natural justice requires not merely procedural compliance but substantive fairness, mandating that disciplinary authorities consider all relevant factors and exclude irrelevant considerations.[12]

- In Managing Director, ECIL v. B. Karunakar (1993), the Court established the right of accused officials to receive copies of inquiry reports before final decisions, adding another procedural layer to the process.[13]

Doctrine of Proportionality in Disciplinary Action

The doctrine of proportionality, imported from administrative law, has further complicated disciplinary decision-making. Courts now routinely examine whether penalties are commensurate with proven misconduct, often substituting their judgment for that of disciplinary authorities.

In Chairman, LIC v. A. Masilamani (2013), the Supreme Court reduced a dismissal to compulsory retirement, finding the original penalty disproportionate despite proven misconduct.[14]

Procedural Complexity and Implementation Challenges

These judicial interventions have created a complex matrix of procedural requirements that disciplinary authorities must navigate carefully. Any deviation, however minor, risks invalidating entire proceedings. The result is a system where procedural perfectionism often trumps substantive justice, creating opportunities for dilatory tactics and strategic litigation.

Systemic Impact and Reform Efforts

The interaction between constitutional provisions, statutory rules, and judicial interpretations has produced a framework that, while comprehensive on paper, struggles with practical implementation.

Constitutional safeguards intended to prevent arbitrary action have been interpreted so expansively that they often prevent legitimate disciplinary action. Statutory procedures designed for administrative efficiency have been overlaid with judicial requirements that transform simple processes into complex legal proceedings.

The cumulative effect is a system that provides extensive protection to accused officials while often failing to deliver timely justice in cases of proven misconduct.

Recent Amendments and Their Limitations

Recent legislative attempts to streamline procedures have met with limited success. The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Amendment Rules, 2018[15], sought to introduce stricter timelines and limit grounds for review, but implementation remains inconsistent across departments.

Similar state-level initiatives have faced resistance from service associations and judicial scrutiny, highlighting the challenges of reform in this domain.

Central Civil Services Disciplinary Framework

The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965, establish a comprehensive and structured framework for disciplinary action that attempts to balance the competing demands of administrative efficiency, procedural fairness, and employee rights. The framework’s architecture reflects careful consideration of various administrative needs while incorporating safeguards against arbitrary action.

Classification of Penalties Under Rule 11

Under Rule 11[16], penalties are systematically classified into minor and major categories, each with distinct procedural requirements and consequences.

| Category of Penalty | Description |

|---|---|

| Minor Penalties | Censure, withholding of promotions, recovery from pay of pecuniary loss caused to government, and withholding of increments. |

| Major Penalties | Reduction to lower time-scale, grade, post or rank; compulsory retirement; removal from service; and dismissal. |

Procedural Differentiation Between Minor and Major Penalties

The procedural framework differentiates between minor and major penalties, establishing proportionate processes for each category.

Procedure for Minor Penalties

For minor penalties, Rule 16[17] provides relatively streamlined procedures involving issuance of a memorandum specifying charges, consideration of the official’s written representation, and a reasoned decision by the competent authority.

Procedure for Major Penalties

Major penalties, however, require extensive processes under Rule 14[18], beginning with the appointment of an inquiry authority and issuance of detailed charge-sheets accompanied by statements of imputation and lists of witnesses and documents.

Inquiry Process for Major Penalties

The inquiry process for major penalties represents the framework’s most complex component.

- Preliminary hearing to determine admitted facts

- Examination of prosecution witnesses

- Cross-examination by the defending official

- Presentation of defense evidence

- Cross-examination by the presenting officer

- Submission of written briefs by both sides

The inquiry officer must prepare a detailed report containing findings on each charge with reasons, which then forms the basis for the disciplinary authority’s decision.

Systemic Challenges in Implementation

Despite the structured nature of these procedures, practical implementation reveals significant systemic challenges. The average duration of disciplinary proceedings in Central services extends to 4-5 years, far exceeding intended timelines.

Contributing factors include chronic shortage of trained inquiry officers, with many departments relying on ad-hoc appointments of officials who lack proper training in quasi-judicial procedures. This shortage often results in the same officials conducting multiple inquiries simultaneously, leading to scheduling conflicts and delays.

Judicial Intervention and Resulting Delays

Judicial intervention represents perhaps the most significant source of delay. The availability of multiple forums for challenging disciplinary actions – departmental appeals, administrative tribunals, High Courts, and the Supreme Court – creates opportunities for prolonged litigation.

Officials routinely file writ petitions challenging preliminary orders, composition of inquiry committees, procedural decisions, and final penalties. Courts, while emphasizing the need for expeditious disposal, often grant stays that effectively suspend proceedings for extended periods.

Evidentiary Standards and Burden of Proof

The evidentiary standards required in disciplinary proceedings have evolved to mirror criminal trials, despite the intended administrative nature of these processes. Inquiry officers, concerned about potential judicial scrutiny, often insist on strict proof requirements, extensive documentation, and formal procedures that extend timelines significantly.

The burden of proof, while formally remaining at the level of preponderance of probability, practically approaches criminal standards in many cases.

Resource Constraints

Resource constraints further complicate implementation. Many departments lack dedicated infrastructure for conducting inquiries, relying on makeshift arrangements that compromise efficiency.

The absence of specialized legal support for presenting officers often results in poorly drafted charge-sheets and inadequate presentation of evidence, providing grounds for successful challenges by defending officials who frequently engage experienced lawyers.

Recent Reform Initiatives

Recent reform initiatives have attempted to address these challenges through various measures.

- The introduction of e-office systems aims to reduce delays in file movement and documentation.

- Video conferencing facilities enable remote testimony, addressing logistical challenges in witness examination.

- Standard operating procedures for common types of misconduct provide templates for charge-sheets and inquiry processes.

However, these reforms have achieved limited success due to incomplete implementation and continued judicial expansion of procedural requirements.

Statistical Insights and Outcomes

The Central Vigilance Commission[19] has documented that approximately 60% of disciplinary proceedings face legal challenges at various stages, with 35% experiencing stays that extend beyond one year.

Analysis of outcomes reveals that while initial charge-sheets propose major penalties in 70% of cases, only 40% ultimately result in such penalties, with many reduced or overturned due to procedural irregularities.

Core Structural Paradox of the Framework

The framework’s fundamental challenge lies in reconciling its administrative purpose with quasi-judicial character imposed by judicial interpretation. Originally designed for efficient internal management of service discipline, the system now functions as a parallel justice system with all attendant complexities but without commensurate resources or expertise.

This transformation has created a paradox where the most serious cases of misconduct often face the longest delays due to heightened procedural scrutiny.

State Civil Services Disciplinary Framework

State civil services operate under diverse disciplinary frameworks that reflect local administrative traditions, political contexts, and varying interpretations of model Central rules. This diversity creates a complex landscape where similar misconduct may face different procedural requirements and outcomes across state boundaries. While most states have adopted rules broadly similar to the CCS framework, significant variations exist in implementation, interpretation, and effectiveness.

Maharashtra: A Comprehensive but Delayed Framework

Maharashtra’s Civil Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules represent one of the more comprehensive state frameworks. The rules closely mirror CCS provisions but incorporate specific amendments addressing local challenges. The state has introduced specialized procedures for corruption cases through the Maharashtra Civil Services (Discipline and Appeal) (Amendment) Rules, 2015[20], which mandate completion of inquiries within 180 days for cases involving financial misconduct.

However, practical implementation reveals that these timelines are rarely met, with average corruption-related proceedings extending to 3–4 years.

Karnataka: Procedural Streamlining with Mixed Results

Karnataka attempted significant streamlining through the Karnataka Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) (Amendment) Rules, 2014.[21] These amendments reduced documentation requirements, simplified inquiry procedures for minor penalties, and introduced deemed approval provisions for cases where higher authorities fail to act within specified timeframes.

Despite these progressive reforms, implementation remains inconsistent across departments. The state’s e-governance initiatives have partially improved process efficiency, but judicial interventions continue to cause substantial delays.

Tamil Nadu: Expedited Provisions Rarely Invoked

Tamil Nadu’s framework includes unique provisions for summary proceedings under Rule 19A of the Tamil Nadu Civil Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules[22], allowing expedited action in cases where misconduct is admitted or conclusively proven through documentary evidence. However, these provisions are rarely invoked due to concerns about potential legal challenges.

The state has also established dedicated vigilance cells in major departments, but resource constraints limit their effectiveness. Analysis of outcomes shows that while Tamil Nadu achieves slightly better completion rates than other states, the average duration still exceeds 5 years.

West Bengal: Limited Modernization and Prolonged Delays

West Bengal presents a contrasting approach with its more traditional framework that has seen limited modernization. The state continues to rely heavily on manual processes and conventional inquiry methods. The West Bengal Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules[23] maintain older procedural requirements that often conflict with contemporary administrative needs.

This has resulted in some of the longest average proceedings in the country, with complex cases routinely extending beyond 8 years.

Uttar Pradesh: Structural and Resource Limitations

Uttar Pradesh, despite being India’s most populous state, struggles with severe resource constraints in implementing disciplinary procedures. The state’s framework, while statutorily similar to CCS rules, suffers from acute shortage of trained personnel, inadequate infrastructure, and overwhelming caseloads.

The Uttar Pradesh Government Servants (Discipline and Appeal) Rules have undergone minimal amendments since their enactment, failing to address contemporary challenges. Consequently, the state reports among the lowest rates of successful penalty implementation.

Common Challenges Across States

Analysis of state-level variations reveals several common challenges:

- Inadequate training infrastructure for inquiry officers, with most states lacking dedicated academies or regular training programs.

- Inconsistent interpretation of procedural requirements across departments and districts.

- Limited coordination between vigilance agencies and regular administrative departments.

- Absence of standardized documentation systems leading to frequent record-keeping errors.

- Varying levels of political interference in disciplinary decisions.

Impact of Decentralization and Administrative Inequities

The decentralized nature of state administrations exacerbates these challenges. District-level authorities often operate with significant autonomy in disciplinary matters, leading to inconsistent application of rules within the same state. Resource disparities between urban and rural administrations create additional inequities, with remote districts facing particular difficulties in conducting proper inquiries.

Financial constraints significantly impact state-level disciplinary mechanisms. Unlike Central services, which benefit from relatively better resource allocation, many states struggle to maintain dedicated disciplinary units. This results in additional responsibilities being assigned to regular administrative staff, who often lack the specialized skills required for conducting quasi-judicial proceedings. The absence of dedicated legal support further handicaps state departments in handling complex cases.

Emerging Reform Models in Progressive States

Recent initiatives by some progressive states offer potential models for reform. Kerala’s experiment with regional disciplinary tribunals has shown promise in standardizing procedures and reducing delays. Telangana’s digital case management system provides real-time tracking of disciplinary proceedings, enhancing transparency and accountability. Gujarat’s mandatory training certification for inquiry officers has improved the quality of proceedings, though implementation challenges persist.

Absence of Inter-State Coordination

Inter-state coordination remains notably absent in disciplinary matters. Officials transferred between states often exploit procedural differences to delay or complicate ongoing proceedings. The lack of information sharing between state vigilance agencies allows some officials to evade accountability by securing transfers to different jurisdictions.

Outcomes and Statistical Impact

| Category of States | Major Penalty Implementation Rate | Average Duration of Proceedings |

|---|---|---|

| Modernized Frameworks with Better Resources | 35–40% | 4–5 Years |

| Traditional Frameworks with Resource Constraints | Below 20% | 7–9 Years (Often Exceeding a Decade) |

Need for Harmonization and Reform

These disparities highlight the need for greater standardization and resource allocation in state services. While respecting federal principles and local autonomy, a degree of harmonization in core procedural requirements could significantly improve efficiency and fairness across jurisdictions.

The current system, with its wide variations and inconsistencies, undermines the fundamental principle of equality before law and creates opportunities for forum shopping and procedural manipulation. State civil services collectively employ over 80% of India’s government workforce, making their disciplinary frameworks crucial for overall administrative accountability.

The persistent challenges in state-level mechanisms therefore represent a significant obstacle to effective governance and public trust in administrative institutions.

Legal Loopholes Undermining Accountability

The disciplinary framework for civil services suffers from numerous legal loopholes that errant officials systematically exploit to evade accountability, creating what has been termed a “culture of impunity” within certain sections of bureaucracy. These loopholes emerge from statutory ambiguities, procedural complexities, conflicting judicial interpretations, and gaps between different regulatory regimes. Their cumulative effect significantly undermines the deterrent value of disciplinary proceedings and erodes public confidence in administrative accountability.

Judicial Review And Constitutional Remedies

The most prominent loophole involves the expansive scope of judicial review available through constitutional remedies under Articles 226 and 32. While these provisions serve the crucial function of preventing administrative excess, their liberal interpretation has enabled civil servants to approach High Courts and the Supreme Court at virtually any stage of disciplinary proceedings.

Quasi-Judicial Character Of Disciplinary Proceedings

The landmark case of Union of India v. Tulsiram Patel (1985) established that departmental proceedings are quasi-judicial, thereby subjecting them to judicial scrutiny for compliance with natural justice principles. While protecting employee rights, this characterization opened floodgates for challenging disciplinary actions on numerous technical grounds.

Expansion Of Natural Justice Requirements

In State of Bihar v. Subhash Singh (1997),[24] the Supreme Court expanded natural justice requirements in disciplinary proceedings, mandating strict procedural compliance. The Court held that even minor deviations could invalidate entire proceedings, regardless of the accused official’s guilt or the misconduct’s severity. This precedent created a framework where technical objections routinely defeat substantive justice, encouraging officials to focus on finding procedural flaws rather than addressing substantive charges.

Intermediate Writ Petitions And Delays

High Court of Judicature at Allahabad v. Rajan Vashisht (2024)[25] represents the most recent judicial attempt to address interminable delays caused by multiple writ petitions. The Supreme Court observed that disciplinary proceedings extending beyond a decade rendered accountability meaningless and directed High Courts to exercise restraint in entertaining petitions against intermediate orders. Despite this clear directive, lower courts continue entertaining such petitions, citing the fundamental right to judicial remedies. The judgment noted that in the Vashisht case, 14 separate writ petitions were filed over eight years, each resulting in stay orders that cumulatively paralyzed the disciplinary process.

Bias Allegations As A Strategic Tool

The exploitation of bias allegations represents another significant loophole.

Challenges To Inquiry Committee Composition

K.R. Deb v. The Collector of Central Excise (2020)[26] highlighted how officials challenge inquiry committee compositions based on alleged bias. The Calcutta High Court quashed seven-year-old proceedings due to perceived bias in selecting inquiry officers, despite no evidence of actual prejudice. The judgment established that mere possibility of bias, however remote, could invalidate proceedings, creating opportunities for strategic challenges to inquiry officer appointments.

Delay-Based Immunity From Accountability

Belated Initiation Of Disciplinary Action

State of Maharashtra v. Sanjay Kumar Gupta (2019)[27] addressed the issue of delayed proceedings, with the Bombay High Court holding that initiating disciplinary action after unreasonable delay violated natural justice principles. The Court set aside proceedings initiated eight years after alleged misconduct, effectively establishing that procedural delays could provide immunity from accountability. This precedent incentivizes officials to create delays through various tactics, knowing that excessive duration might ultimately void the proceedings.

Jurisdictional Conflicts And Inter-Governmental Disputes

T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad v. Union of India (2018)[28] demonstrated how jurisdictional challenges create additional delays. The Supreme Court spent three years determining whether disciplinary proceedings against forest officers fell under state or Central jurisdiction. During this period, no action could proceed against accused officials, highlighting how inter-governmental disputes can be exploited to suspend accountability mechanisms indefinitely.

Evidentiary And Documentary Loopholes

Documentary requirements present another exploitable loophole. The insistence on strict proof standards, approaching those in criminal trials, often proves impossible to meet in administrative contexts. Officials routinely challenge the authenticity, admissibility, or sufficiency of evidence, forcing departments to meet evidentiary standards that were never contemplated for administrative proceedings. The absence of clear guidelines on electronic evidence further complicates matters in an increasingly digital workplace.

Multiplicity Of Forums And Forum Shopping

The multiplicity of forums for appeal and review creates a complex maze that officials navigate strategically. Beyond departmental appeals, officials can approach Administrative Tribunals, High Courts, and the Supreme Court, often simultaneously. This parallel processing not only delays resolution but creates conflicting orders that further complicate proceedings. The lack of clear demarcation between these forums’ jurisdictions enables forum shopping and duplicative litigation.

Technical Defects In Charge-Sheets

Procedural requirements regarding charge-sheet drafting have become increasingly technical, with courts quashing proceedings for minor drafting defects. The Supreme Court’s insistence that charge-sheets must be precise, specific, and comprehensive has led to a situation where drafting errors, however inconsequential, can invalidate entire proceedings. This technicality is frequently exploited by officials who engage experienced lawyers to identify drafting deficiencies.

Misuse Of Parity In Punishment

The principle of parity in punishment, while ensuring fairness, has been misused to challenge penalties. Officials argue that similar misconduct by others received lighter punishment, forcing disciplinary authorities to maintain detailed databases of past penalties and justify any variations. This requirement not only complicates decision-making but provides another ground for challenging otherwise justified penalties.

Transfer And Hearing-Related Loopholes

- Transfer-related loopholes allow officials to evade proceedings by securing postings to different departments or states. Once transferred, questions arise about which authority should continue proceedings, what rules apply, and how evidence should be collected across jurisdictions. These administrative complications often result in proceedings being dropped or restarted, causing further delays.

- The requirement for personal hearings at multiple stages creates logistical challenges that officials exploit through repeated adjournment requests. Combined with liberal court attitudes toward granting time, this procedural requirement transforms into a delay tactic that can extend proceedings indefinitely.

Cumulative Impact On Accountability

These loopholes operate synergistically, creating a system where determined officials can delay proceedings almost indefinitely through strategic litigation and procedural challenges. The cumulative effect undermines the fundamental purpose of disciplinary mechanisms, transforming them from tools of accountability into procedural labyrinths that protect the very misconduct they were designed to prevent.

Procedural Delays and Their Impact

Procedural delays constitute the most pervasive challenge in civil service disciplinary proceedings, creating a cascade effect that undermines administrative efficiency, employee morale, and public trust. These delays originate from multiple sources and compound throughout the process, often extending proceedings far beyond reasonable timeframes.

Delays at the Preliminary Inquiry Stage

The initial delay typically occurs during preliminary inquiry, where departments take months or years to determine whether formal proceedings should begin. This stage suffers from unclear guidelines, lack of dedicated personnel, and bureaucratic inertia.

- Absence of clear timelines for preliminary inquiries

- Inadequate staffing and lack of specialized officers

- Administrative hesitation and bureaucratic inertia

Delays During Formal Proceedings

Once formal proceedings commence, the issuance and service of charge-sheets encounter further delays as officials claim non-receipt or request additional time to respond.

The appointment of inquiry officers presents another significant bottleneck. Senior officials are reluctant to accept these assignments, viewing them as additional burdens with limited rewards. When appointed, inquiry officers must balance these responsibilities with regular duties, resulting in irregular hearing schedules and protracted proceedings.

The inquiry stage is particularly susceptible to delays due to:

- Witness unavailability

- Document retrieval issues

- Strategic adjournment requests by defending officials

Post-Inquiry and Decision-Making Delays

Post-inquiry delays are equally problematic, with inquiry reports taking months to prepare and submit. The disciplinary authority must then provide another opportunity for the charged official to respond, followed by multi-level consultations before issuing final orders.

The average duration from initiation to conclusion now exceeds 4–5 years in Central services and 6–8 years in state services.

Institutional and Public Impact of Delays

These delays exact a heavy toll on institutional effectiveness.

- Departmental morale suffers when honest officials witness colleagues escaping timely punishment for misconduct.

- Public confidence erodes as high-profile cases drag on without resolution.

- The deterrent effect of disciplinary action diminishes when potential wrongdoers perceive that procedural complexities offer effective immunity from consequences.

Comparative Analysis of the Outcomes

Comparative analysis reveals striking disparities between Central and State services in disciplinary outcomes.

Central Services Outcomes

- Approximately 40% of initiated proceedings result in major penalties

- 30% result in minor penalties

- 30% are dropped or result in exoneration

- Average time from initiation to final order: 4.2 years

State Services Outcomes

State services present more varied outcomes.

| State Category | Major Penalty Rate | Average Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu | Around 35% | Approximately 5.8 years |

| States with weaker infrastructure | As low as 20% | 7+ years |

The quality of inquiry proceedings varies significantly, with Central services benefiting from trained inquiry officers and standardized procedures, resulting in fewer successful legal challenges.

Appeal Outcomes and Procedural Quality

Appeal outcomes further illustrate these disparities.

- In Central services, 25% of penalties are reduced or overturned on appeal, primarily due to procedural irregularities.

- In state services, this figure rises to 40%, reflecting greater procedural inconsistencies and variable quality of initial decisions.

Judicial Intervention and Administrative Autonomy

The relationship between judicial oversight and administrative autonomy presents a fundamental tension in disciplinary matters. While judicial review ensures fairness and prevents arbitrary action, excessive intervention has created a system where administrative efficiency is frequently sacrificed at the altar of procedural perfectionism.

Courts have progressively expanded review scope from examining jurisdictional errors to scrutinizing procedural minutiae. This expansion reflects broader judicial activism but creates practical challenges for administrative authorities navigating increasingly complex procedural requirements.

The doctrine of proportionality has further complicated decision-making, with courts routinely substituting their judgment for that of disciplinary authorities.

Recent Judicial Trends and Challenges

Recent judicial pronouncements have attempted to restore balance, emphasizing the need for judicial restraint in administrative matters. However, implementation remains inconsistent, with many High Courts continuing to entertain petitions on minor procedural grounds.

Recommendation for Reforms

Comprehensive reform of the disciplinary framework requires a multi-dimensional approach addressing systemic weaknesses at various levels.

Binding Timelines and Accountability

- First and foremost, binding timelines must be established for each procedural stage with meaningful consequences for non-compliance.

- These timelines should be realistic but strictly enforced, allowing limited extensions only in demonstrably exceptional circumstances.

- The failure to adhere to these timelines should result in automatic consequences, such as deemed approvals or adverse findings against the party responsible for delay, creating strong incentives for expeditious processing.

Dedicated Disciplinary Tribunals

The creation of dedicated disciplinary tribunals with specialized expertise would significantly improve the quality and efficiency of proceedings.

- These tribunals, staffed by members with administrative and legal experience, would handle all service matters.

- This would reduce the burden on regular courts and ensure consistent application of principles.

- Their specialized nature would allow for the development of jurisprudence specific to service matters, reducing uncertainties that currently plague the system.

- These tribunals should have clearly defined jurisdiction and limited grounds for appeal to prevent the current proliferation of litigation across multiple forums.

Streamlining Charge-Sheet Processes

Streamlining charge-sheet processes through standardized templates for common types of misconduct would eliminate a major source of procedural delays and technical challenges.

- Clear guidelines on evidence requirements, combined with pre-inquiry conferences to narrow issues and agree on procedural matters, would focus proceedings on substantive issues rather than technical compliance.

- This reform would reduce the incidence of proceedings being quashed on technical grounds while ensuring adequate notice to accused officials.

Technology Integration in Disciplinary Proceedings

Technology integration offers substantial potential for improving efficiency across all stages of disciplinary proceedings.

| Area | Proposed Technological Measure | Intended Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Case Tracking | Digital case management systems | Tracking proceedings, flagging delays, automating routine communications |

| Witness Testimony | Video conferencing facilities | Address logistical challenges, especially in multi-location cases |

| Documentation | Electronic documentation and digital signatures | Streamlined record-keeping and reduced disputes over authenticity |

Addressing Resource Constraints

Finally, addressing resource constraints through dedicated budgetary allocations is essential for any reform to succeed.

- Disciplinary departments require adequate personnel, infrastructure, training facilities, and technological upgrades to function effectively.

- This investment should be viewed not as administrative overhead but as crucial for maintaining institutional integrity and public trust.

- Proper resourcing would enable departments to maintain dedicated inquiry officers, provide continuous training, and ensure timely completion of proceedings.

- Without addressing these fundamental resource issues, even the best-designed reforms will fail to achieve their intended objectives.

Conclusion

The comparative study reveals a disciplinary system struggling to balance fairness and efficiency. Legal loopholes and systemic delays create an environment where accountability is frequently compromised.

- While Central services maintain relatively effective mechanisms despite challenges, state services face greater difficulties due to resource constraints and procedural variations.

- Reform efforts must focus on standardizing procedures, enforcing timelines, limiting judicial intervention, enhancing administrative capacity, and leveraging technology.

- These reforms should be guided by the principle that procedural fairness and administrative efficiency are complementary rather than competing objectives.

The path forward requires commitment from all stakeholders – legislature, judiciary, and executive – to prioritize administrative accountability while protecting legitimate employee rights.

Only through coordinated effort can the disciplinary framework fulfill its essential role in maintaining integrity and effectiveness in India’s civil services. End Notes:

- Mishra, P. and Kumar, S., “Efficiency Analysis of Disciplinary Proceedings in Central Civil Services,” 43 Administrative Law Review 234-256 (2019).

- Sharma, M., “State-level Variations in Civil Service Disciplinary Proceedings,” 28 Journal of Governance Studies 89-112 (2020).

- Rao, K.V., Administrative Accountability in Civil Services (Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Law Commission of India, 275th Report on Implementation of Disciplinary Proceedings in Civil Services (Government of India, 2017).

- Gupta, A. and Verma, R., “Implementation of Disciplinary Reforms in Civil Services,” Indian Journal of Public Administration, 67(2), 156-175 (2021).

- Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965, Gazette of India, Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions.

- Constitution of India, 1950, art. 311.

- Ibid.

- All India Services Act, 1951, No. 61 of 1951.

- Maharashtra Civil Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules, 1979.

- Union of India v. Tulsiram Patel, (1985) 3 SCC 398.

- Bihar v. Subhash Singh, (1997) 2 SCC 217.

- ECIL v. B. Karunakar, (1993) 4 SCC 727.

- Chairman, LIC v. A. Masilamani, (2013) 12 SCC 1.

- The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Amendment Rules, 2018, Notification No. GSR 456(E), Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, Government of India.

- The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965, Rule 11, Notification No. 11012/4/58-Estt.(A), Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, Government of India.

- The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965, Rule 16, Notification No. 11012/4/58-Estt.(A), Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, Government of India.

- The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965, Rule 14, Notification No. 11012/4/58-Estt.(A), Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, Government of India.

- The Central Vigilance Commission Act, 2003, Act No. 45 of 2003, Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India.

- The Maharashtra Civil Services (Discipline and Appeal) (Amendment) Rules, 2015, Government of Maharashtra.

- Karnataka Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) (Amendment) Rules, 2014, Government of Karnataka.

- Rule 19A, Tamil Nadu Civil Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules, Government of Tamil Nadu.

- West Bengal Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules, Government of West Bengal.

- State of Bihar v. Subhash Singh, (1997) 6 SCC 323.

- Allahabad v. Rajan Vashisht, (2024) 3 SCC 112.

- K.R. Deb v. The Collector of Central Excise, (2020) 2 SCC 134.

- State of Maharashtra v. Sanjay Kumar Gupta, (2019) 6 SCC 788.

- T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad v. Union of India, (2018) 10 SCC 1.