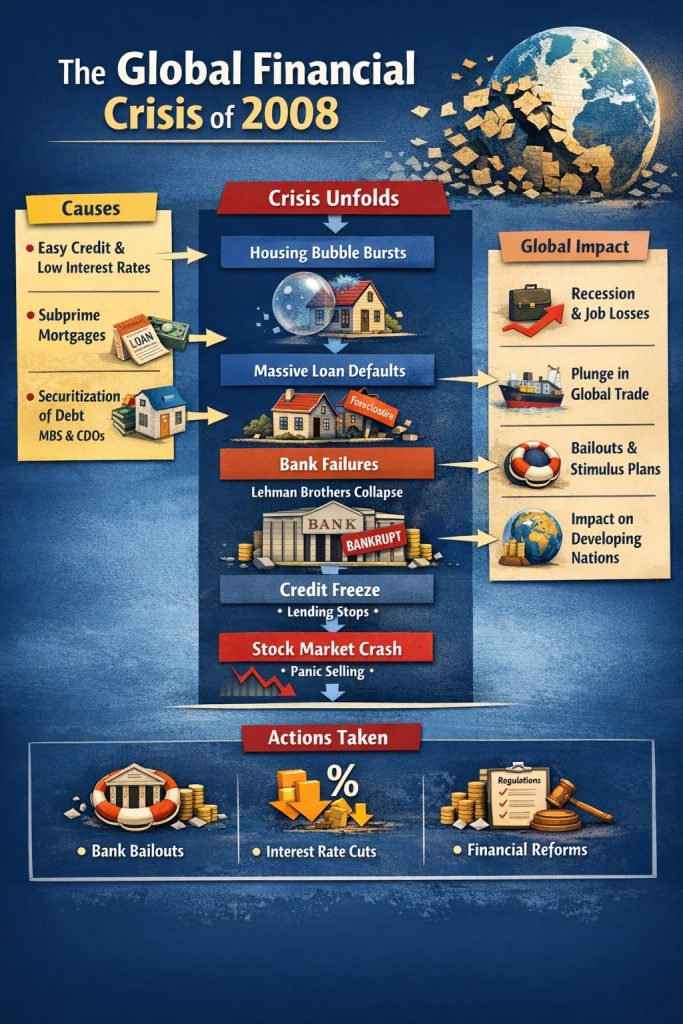

The global financial crisis—widely regarded as the most severe economic downturn since the 1930s Great Depression—triggered profound disruptions across international financial systems and necessitated extensive government intervention (Lu, 2023). It revealed critical vulnerabilities within the financial sector, where inadequate oversight and the widespread use of dangerously complex financial instruments left the economy exposed (Needham & Needham, 2023). Originating in the U.S. housing sector, the crisis quickly spread worldwide through interconnected financial markets and global trading networks (Uçar, 2025). A surge in home prices was fueled by historically low interest rates in the aftermath of the 2000 dot-com collapse, along with easy access to credit, ultimately leading to an unstable housing bubble and a wave of subprime mortgage defaults (Huang, 2025; Uçar, 2025).

These conditions, combined with accommodative monetary policies and minimal regulatory constraints, allowed sophisticated financial tools like credit default swaps to multiply rapidly (Guo, 2024; Su, 2023). As these instruments became concentrated within large financial institutions, they amplified systemic risk, paving the way for widespread insolvencies and institutional failures (Karol, 2020). Murphy (2008) highlights that the unregulated market for credit default swaps ballooned from $900 billion to more than $50 trillion, significantly undermining market stability and intensifying the crisis.

Severity of Impact

High | ██████████████ Banking Sector

| ████████████ Global Trade

Medium | █████████ Employment

Low | █████ Developing Economies (initially)

- The Roots: Low Interest Rates and the Housing Bubble

The genesis of the mid-2000s financial crisis lay in the economic volatility that followed the dot-com collapse and the September 11th attacks. In an effort to stabilize the economy, the Federal Reserve drastically reduced interest rates to historically inexpensive levels. This influx of liquidity pushed investment away from the security of bonds and into the more dynamic real estate sector. Simultaneously, federal policies championing universal homeownership led to a relaxation of lending standards. This environment permitted the widespread issuance of subprime mortgages—high-risk credit extended to individuals with poor financial histories—creating the conditions for the market’s eventual implosion.

- Securitization and Derivatives in Financial Innovation

A sophisticated web of financial schemes amplified the severity of the crisis. At its core, investment banks utilized a process they dubbed “securitization,” aggregating thousands of individual home loans into single, tradable instruments known as Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS). These were then sliced into layers of varying risk, called “tranches,” and marketed to a global audience of investors.

To enhance the appeal of these already hazardous assets, banks engineered even more intricate products called Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). In a critical failure, Credit Rating Agencies—hobbled by significant conflicts of interest—issued their highest “AAA” ratings for these complex constructions, willfully ignoring that they were built on a foundation of high-risk subprime mortgages. Compounding the danger, Credit Default Swaps (CDS) acted as a form of pseudo-insurance against bond failures, creating an immense, hidden lattice of debt across the system. Because these derivatives operated in a regulatory blind spot—what became known as the “shadow banking system”—oversight authorities were completely unaware of the true scale of the mounting risk.

- The Collapse: From Subprime to Systemic

The housing bubble burst in 2006–2007 as the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates, triggering widespread defaults among subprime borrowers facing soaring adjustable mortgage payments. Foreclosures surged, flooding the market and causing home prices to collapse. Once-prized “AAA-rated” mortgage-backed securities and CDOs turned into toxic assets, their value uncertain, sparking a global liquidity crisis. By 2008, banks stopped lending to each other over solvency fears. The crisis peaked in September 2008 with the bankruptcy of 158-year-old Lehman Brothers, shattering confidence and proving even giant institutions were vulnerable. Financial turmoil spread worldwide, intensifying credit freezes and marking the worst economic downturn in decades.

- Global Contagion and the Great Recession

The crisis moved from Wall Street rapidly to “Main Street.” The freezing of credit markets left businesses unable to get loans to pay employees or purchase inventory. Trade on a world scale collapsed, and stock markets plummeted, wiping out trillions of dollars in household wealth. European banks — heavy investors in U.S. toxic assets — encountered the same insolvency. Countries like Iceland had their entire banking systems collapse, while others, such as Greece and Ireland, had sovereign debt crises. Governments found themselves forced to intervene with massive taxpayer-subsidized “bailouts” (e.g., the $700 billion TARP program in the U.S.) to stave off a total collapse of the global capitalist order.

- Conclusion: A Failure of Oversight

The 2008 collapse happened as a result of ignored warning signs — rising consumer indebtedness, exploitative lending, and unregulated financial instruments — while “market fundamentalism” took as given the idea that it was able to self-regulate, risk take with impunity. The crisis was a massive failure of ethics and oversight, an example of how the instability of one market (that was, American housing) could destabilize the global economy, under the burden of excessive debt, and under the gaze of opaque systems. Regulatory reforms, such as the Dodd-Frank Act, were designed to avoid that kind of systemic risk by ensuring new oversight that would safeguard against recurrence.