The Customs Act, 1962 serves as India’s principal legislation governing customs duties on goods imported into or exported from the country. Enacted to consolidate and modernize the fragmented pre-independence customs laws, it comprehensively regulates the levy, assessment, calculation, collection, and recovery of import and export duties.

The Act empowers customs authorities to prevent smuggling, protect domestic industries from unfair competition, regulate international trade flows, and safeguard national revenue. It operates in harmony with allied statutes, including the Customs Tariff Act, 1975 (for tariff schedules), the Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992 (for trade policy control), and the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (for forex-related aspects of trade).

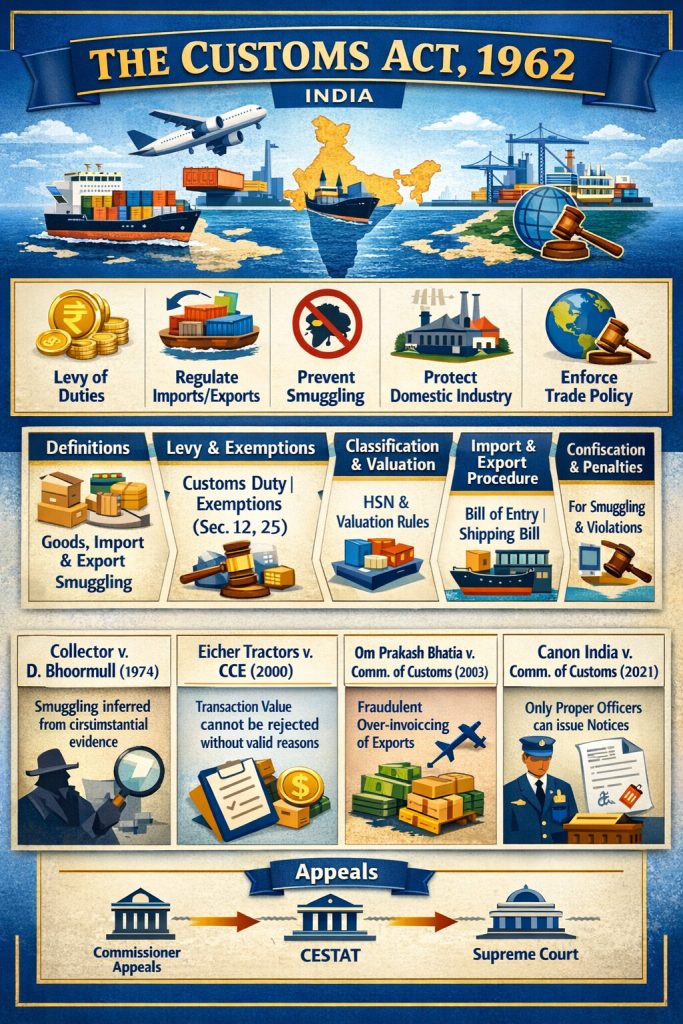

Objectives of the Customs Act, 1962

The Customs Act, 1962 is a comprehensive legislation in India whose primary objectives are to levy and collect customs duties on imports and exports, regulate the lawful flow of international trade, prevent smuggling and other economic offences, protect domestic industries from unfair foreign competition, and ensure effective enforcement of India’s trade policies as well as compliance with international trade obligations and commitments.

Important Definitions (Section 2)

The Act defines key terms to delineate its scope and application. “Goods” under Section 2(22) broadly includes vessels, aircraft, vehicles, currency, baggage, and stores. “Import” (Section 2(23)) means bringing goods into India from outside, while “export” (Section 2(18)) refers to taking goods out of India. “Dutiable goods” (Section 2(14)) are those chargeable to customs duty, and “smuggling” (Section 2(39)) covers any import or export in contravention of the Act. In Collector of Customs v. D. Bhoormull (1974), the Supreme Court ruled that smuggling, being clandestine, can be validly inferred from circumstantial evidence even without direct proof.

Levy and Exemption from Customs Duty

Under Section 12, customs duty is levied on all goods imported into or exported from India, with rates specified in the Customs Tariff Act, 1975. Section 25 empowers the Central Government to grant exemptions—absolute or conditional—from such duty in the public interest, through notifications.

In Union of India v. Indian Aluminium Co. (1996), the Supreme Court held that exemption notifications must be strictly construed, and any ambiguity in their interpretation should be resolved in favour of the Revenue (government).

Classification and Valuation of Goods

Goods are classified for customs duty purposes using the Harmonised System of Nomenclature (HSN), which ensures uniformity in international trade. In Dunlop India Ltd. v. Union of India (1976), the Supreme Court held that classification must be determined by the common trade parlance or commercial understanding rather than technical or scientific meanings. Under Section 14, the customs value is primarily the transaction value—the price actually paid or payable for the goods when sold for export to India—subject to adjustments as per the Customs Valuation (Determination of Value of Imported Goods) Rules, 2007.

Import and Export Procedures

For imports, the procedure involves filing a Bill of Entry, assessment of duty by customs authorities, payment of assessed duty, and eventual clearance of goods. For exports, an exporter files a Shipping Bill, followed by customs examination of goods, and issuance of the Let Export Order (LEO) to permit shipment. Misdeclaration, such as an importer understating invoice value to evade duty, attracts confiscation liability under Section 111 as improper importation.

Baggage, Warehousing, and Transshipment

Under Sections 77–81, passengers must declare dutiable articles in their baggage; failure to do so attracts confiscation and penalties. In Kailash Chand Jain v. Union of India (2003), the Supreme Court upheld confiscation of undeclared gold in passenger baggage. Sections 57–73 provide for warehousing, allowing importers to store goods in customs-bonded warehouses with deferred duty payment until clearance. Section 54 permits transshipment of goods from one customs station to another within India without payment of duty, subject to prescribed safeguards and supervision.

Under Section 11, the Central Government is empowered to prohibit the import or export of certain goods wholly or conditionally in the interests of public order, morality, security of India, public health, conservation of flora and fauna, prevention of depletion of exhaustible resources, or regulation of foreign exchange. Violation of such prohibitions constitutes smuggling. In Sheikh Mohd. Omer v. Collector of Customs (1970), the Supreme Court held that importing goods in contravention of a prohibition notification amounts to smuggling, attracting confiscation and penalties.

Confiscation of Goods and Conveyances

Under Sections 111 and 113 of the Customs Act, 1962, goods are liable to confiscation for misdeclaration, prohibited import or export, and undervaluation, while Section 115 extends confiscation to conveyances used in smuggling; in Gian Chand v. State of Punjab (1962), the Supreme Court held that confiscation proceedings are civil in nature.

Penalties and Prosecution

Under the Customs Act, 1962, Sections 112, 114, and 114A provide for monetary penalties on persons involved in improper import or export of goods, including acts such as misdeclaration, evasion of duty, or fraudulent practices, and these penalties may be imposed in addition to confiscation and prosecution as prescribed under the Act.

Prosecution (Section 135)

Under Section 135 of the Customs Act, 1962, offences involving high-value goods, fraud, or mens rea (intent to evade duty or wrongfully claim benefits) attract criminal prosecution, punishable with imprisonment (up to 7 years in aggravated cases) and fine.

In Om Prakash Bhatia v. Commissioner of Customs (2003), the Supreme Court held that over-invoicing exports to fraudulently claim export incentives constitutes a serious offence involving mens rea and fraud.

Search, Seizure, and Arrest Powers

Under Sections 100–110, empowered customs officers may search suspected persons/premises (e.g., Sec. 100: persons entering/leaving India; Sec. 105: premises), seize goods/documents liable to confiscation (Sec. 110), and detain relevant items upon reasonable belief.

Under Section 104, officers can arrest persons believed to have committed specified offences (e.g., under Sec. 135), inform grounds of arrest, and produce before a magistrate without delay. Customs officers are not “police officers” (as held in Poolpandi v. Superintendent, Central Excise, 1992 SC), making confessions/statements recorded by them admissible in evidence.

Adjudication and Appeals

Under Section 122 of the Customs Act, 1962, adjudication of customs disputes is a quasi-judicial function exercised by designated customs authorities. The appellate hierarchy extends from the Commissioner (Appeals) to CESTAT, the High Court, and finally the Supreme Court.

In Canon India Pvt. Ltd. v. Commissioner of Customs (2021), the Supreme Court initially held that only duly appointed “proper officers” could issue demand notices under Section 28. However, this was overruled in the November 2024 review judgment, affirming DRI officers as proper officers. On arrest safeguards, the 2025 ruling in Radhika Agarwal v. Union of India clarified that BNSS 2023 provisions (e.g., informing relatives, access to counsel) apply to customs arrests under Section 104, reinforcing constitutional protections.

“To issue demand notices” means to formally require a person (such as an importer or exporter) to pay customs duty, interest, or penalty that the authorities claim is due, by serving an official written notice under the Customs Act (typically under Sections 28 or 124), calling upon the person to explain or pay the alleged dues within a specified time.

Settlement and Compounding

Chapter XIV-A of the Customs Act, 1962 (Section 127; 127A-127N) provides for settlement of disputes through the Settlement Commission, enabling assessees to make a voluntary disclosure of duty liability for expeditious resolution. Separately, compounding of offences permits prescribed customs violations to be settled by payment of a compounding amount, avoiding prolonged prosecution.

Offences by Companies (Section 140)

Section 140 of the Customs Act, 1962 deals with offences by companies and provides that where an offence under the Act is committed by a company, every person who, at the time of commission of the offence, was in charge of and responsible for the conduct of the business of the company shall be deemed to be guilty, if the offence was committed with his consent, connivance, or attributable to his neglect; such liability extends to directors, managers, secretaries, or other officers of the company.

The Supreme Court in Standard Chartered Bank v. Directorate of Enforcement (2005) authoritatively held that companies can be prosecuted for economic offences, even where the prescribed punishment includes mandatory imprisonment, and that prosecution of a company does not fail merely because imprisonment cannot be imposed, thereby reinforcing the principle of corporate criminal liability under economic and fiscal laws.

International Trade and WTO Compatibility

The Act aligns with WTO Valuation Agreement, Trade Facilitation Agreement, and international customs conventions

Police Powers to Investigate and Arrest

Under the Customs Act, 1962, the primary authority to investigate customs offences—such as smuggling, duty evasion, and offences punishable under Section 132 or Section 133 or Section 135 or Section 135A or Section 136 and to arrest without warrant in cognizable cases vests in duly empowered customs officers under Section 104, and not in the regular police. Although customs officers are not ‘police officers’ in the strict sense, they exercise analogous powers of search, seizure, interrogation, and arrest, subject to constitutional and Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, (BNSS) 2023 safeguards, including the requirement of ‘reasons to believe,’ communication of grounds of arrest, and production before a magistrate without unnecessary delay.

The police may, however, intervene in a limited or ancillary capacity—such as where distinct cognizable offences under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, (BNS) 2023 are disclosed, an FIR is registered, or in joint or coordinated operations with customs authorities—since BNSS provisions apply supplementarily to arrests under revenue laws, as clarified by the Supreme Court (including recent jurisprudence such as Radhika Agarwal v. Union of India). Nevertheless, the core responsibility for investigation and prosecution of Customs Act offences continues to rest with the customs authorities, and not with the police undertaking an independent, full-fledged investigation under the Act.

Loopholes in the Customs Act

The Customs Act, 1962, though a cornerstone of India’s trade regulation, has attracted criticism for loopholes and ambiguities that enable misuse and procedural delays. Persistent issues include prolonged provisional assessments, despite partial correction through the 2025 amendments, ambiguities in valuation and classification leading to disputes, and misuse of duty drawback and over-invoicing schemes for fraudulent gains.

Further concerns arise from frequent regulatory changes that create compliance uncertainty and interpretational challenges in rules of origin under Free Trade Agreements, where vague documentation requirements allow circumvention. These gaps have resulted in increased litigation and inconsistent enforcement, undermining predictability for importers and exporters.

Owing to its age, the Act has also been criticised as outdated in the context of modern, digitalised global trade. While recent reforms under the Finance Act, 2025—such as time-bound assessments, voluntary entry revisions, and abolition of the Settlement Commission—seek to address deficiencies, experts argue that a more comprehensive overhaul is necessary for transparency, reduced litigation, and alignment with contemporary trade practices.

Difference Between India’s Customs Act, 1962 and Customs Laws in Developed Countries

India’s Customs Act, 1962 adopts an enforcement-oriented approach, vesting customs officers with wide discretionary powers for searches, seizures, arrests, and post-clearance audits. This often leads to valuation disputes, prolonged provisional assessments, frequent litigation, manual interventions, and higher compliance costs, reflecting its historical emphasis on revenue protection and anti-smuggling in a developing economy.

In contrast, customs laws in developed countries (e.g., US CBP, EU Union Customs Code, Singapore, Japan) prioritize trade facilitation, predictability, and voluntary compliance. They feature binding advance rulings, risk-based selective inspections, extensive digital platforms (e.g., automated filing and AI-driven clearance), strict time-bound processing, greater transparency, and strong alignment with WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement principles to minimize delays and enhance efficient global trade.

Conclusion

The Customs Act, 1962 remains India’s cornerstone legislation for regulating international trade, levying and collecting customs duties on imports and exports, while ensuring lawful movement of goods, facilitating genuine commerce, and combating smuggling and economic offences. Through evolving judicial interpretations, periodic amendments, adoption of digital clearance systems, and alignment with global trade reforms (including WTO commitments and open-market policies), the Act has adapted to contemporary needs. Effectively implemented, it strengthens India’s economy, promotes fair and transparent trade practices, safeguards national revenue, and upholds international obligations, positioning it as an indispensable pillar of the country’s trade and fiscal framework.