An injunction is a court order that either restrains a person from doing a particular act or directs them to perform a specific act. In India, the law relating to injunctions is mainly governed by the Specific Relief Act, 1963 (Sections 36 to 42) and the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (Order XXXIX Rules 1 & 2 for temporary injunctions).

Injunctions are discretionary remedies, granted by courts to prevent irreparable harm where monetary compensation would not be an adequate remedy. Rooted in principles of equity, injunctions play an important role in Indian civil law by preventing wrongful acts and protecting legal rights.

Statutory Framework Governing Injunctions

In India, the law relating to injunctions is mainly governed by Sections 36 to 42 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963 and Order XXXIX Rules 1 and 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. Section 36 states that courts may grant preventive relief through injunctions, either temporary or permanent, at their discretion. These provisions lay down when and how courts can restrain parties or direct them to act in order to prevent injustice.

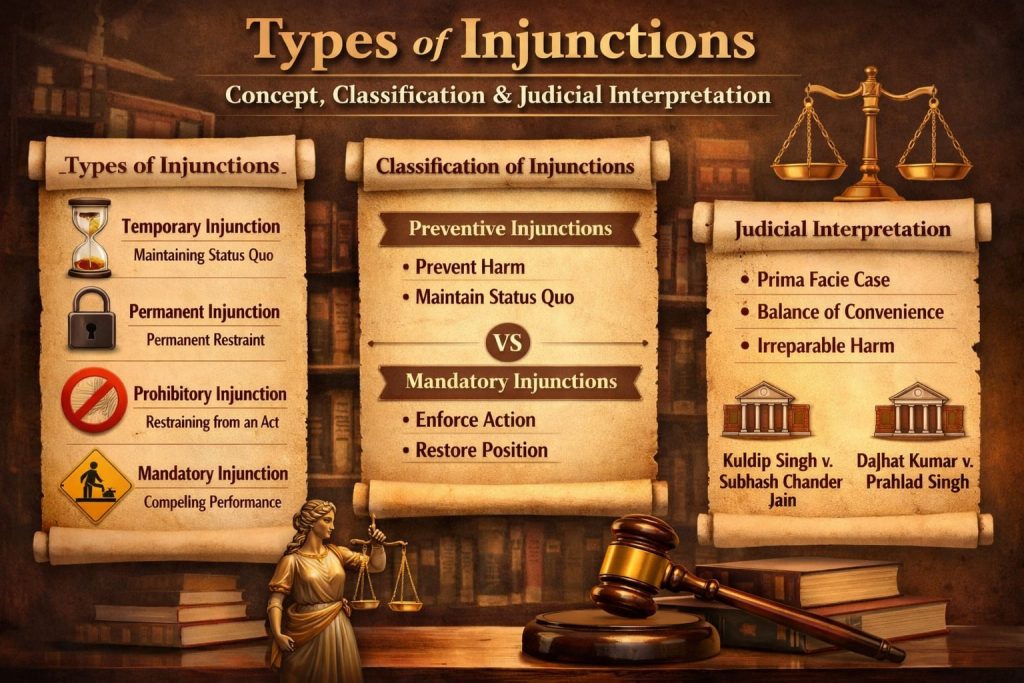

Types of Injunctions in India

Temporary (or interim) Injunction

A temporary (or interim) injunction is a short-term court order granted for a limited period or until the final decision of the case. Its main purpose is to protect the subject matter of the dispute and maintain the existing position between the parties so that no irreparable harm is caused while the case is pending.

Such injunctions are governed by Order XXXIX Rules 1 and 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. For example, a court may restrain a defendant from selling or transferring disputed property during the pendency of a suit.

Courts grant a temporary injunction only when three essential conditions are satisfied: the plaintiff must show a prima facie case, the balance of convenience must favour the plaintiff, and there must be a likelihood of irreparable injury if the injunction is not granted.

Three Conditions for Granting an Injunction

|

Step |

Condition |

Key Question to Ask |

Leading Case Reference |

If Not Satisfied |

|

1 |

Prima Facie Case |

Does the plaintiff have a strong initial case on merits? |

Dalpat Kumar (1992), Wander Ltd. (1990) |

Application fails immediately |

|

2 |

Balance of Convenience |

Will refusing injunction cause greater harm to plaintiff than granting it would to defendant? |

American Cyanamid (UK influence), Indian cases |

Usually refused |

|

3 |

Irreparable Injury |

Will the plaintiff suffer harm that money alone cannot fix? |

Gujarat Bottling, Dorab Cawasji Warden |

Refused – damages are adequate remedy |

In Dalpat Kumar v. Prahlad Singh (1992) 1 SCC 719, the Supreme Court held that the grant of a temporary injunction is a discretionary relief and must satisfy this three-fold test.

Similarly, in Wander Ltd. v. Antox India Pvt. Ltd. (1990), the Court emphasized that interim injunctions should preserve the status quo when legal rights are disputed. Recent judicial decisions continue to affirm that temporary injunctions cannot be granted mechanically and must be supported by clear legal grounds.

Permanent (Perpetual) Injunction

A permanent injunction is granted by the court through a final decree after full trial and adjudication of the dispute. It permanently restrains the defendant from committing a particular act that would violate the plaintiff’s legal rights. Section 38 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963 empowers courts to grant such injunctions, especially where there is a clear and continuing obligation in favour of the plaintiff. A common example is restraining a person from interfering with another’s peaceful and lawful possession of property.

In Kuldip Singh v. Subhash Chander Jain (2000) 4 SCC 50, the Supreme Court held that a permanent injunction may be granted to prevent the breach of an existing legal obligation owed to the plaintiff. Similarly, in Walter Louis Franklin v. George Singh (1996), the Court granted a perpetual injunction on the basis of settled possession, emphasizing that lawful possession can be protected by injunction even against competing claims of ownership.

Mandatory Injunction

A mandatory injunction is a court order that directs the defendant to perform a specific act in order to restore the earlier position that existed before the wrongful act was committed. It is governed by Section 39 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963, and is commonly granted in situations such as directing the demolition of an illegal or unauthorized construction. Unlike prohibitory injunctions, mandatory injunctions require active compliance by the defendant.

In Dorab Cawasji Warden v. Coomi Sorab Warden (1990) 2 SCC 117, the Supreme Court held that mandatory injunctions should be granted only in exceptional circumstances and require a higher standard of proof. The Court stressed that such relief is discretionary and must be supported by strong pleadings and clear evidence. This position was reaffirmed in a 2025 Supreme Court judgment relating to the allotment of alternative plots, where the Court reiterated that a mandatory injunction under Section 39 can be granted only upon a clear breach of an enforceable legal obligation and when strict legal requirements are fully satisfied.

In Estate Officer, Haryana Urban Development Authority v. Nirmala Devi (July 2025), the Supreme Court clarified that mandatory injunctions are discretionary and require strict compliance with an enforceable legal obligation. It cannot bypass policy conditions (e.g., procedural requirements like earnest money deposits in land acquisition rehabilitation cases). The Court outlined six conditions for granting such relief, reinforcing that it applies only to clear breaches.

Prohibitory Injunction

A prohibitory injunction is a court order that restrains a party from doing an act that would infringe or violate the legal rights of the plaintiff. For example, a court may restrain a company from using another party’s registered trademark. In Gujarat Bottling Co. Ltd. v. Coca Cola Co. (1995) 5 SCC 545, the Supreme Court emphasized that such injunctions are meant to prevent threatened injury and to preserve the existing state of affairs until the dispute is finally resolved.

Preventive Injunction

A preventive injunction is granted to stop a wrongful act before it occurs, rather than providing compensation after the damage has been done. Its statutory basis lies in Section 36 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963, which empowers courts to grant preventive relief. In Union of India v. Era Educational Trust (2000) 5 SCC 57, the Supreme Court affirmed that injunctions are essentially preventive in nature and are intended to restrain an apprehended or threatened injury.

Injunction to Restrain Breach of Contract

Courts may grant an injunction to restrain a party from breaching a negative covenant contained in a contract. This power is recognized under Section 42 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963, which allows enforcement of negative obligations even when the contract itself cannot be specifically enforced. For example, a court may restrain an employee from working for a competing employer during the subsistence of the employment contract.

In Niranjan Shankar Golikari v. Century Spinning & Manufacturing Co. (1967) 2 SCR 378, the Supreme Court upheld a negative covenant that restricted an employee from engaging in competing employment during the term of the service contract, holding that such a restriction during employment is legally valid.

Temporary Mandatory Injunction

A temporary mandatory injunction directs a party, at an interim stage of the case, to reverse or correct a wrongful act already committed, in order to preserve justice until the final decision is made.

In Samir Narain Bhojwani v. Aurora Properties (2018) 17 SCC 203, the Supreme Court held that temporary mandatory injunctions should be granted only in rare and clear cases. The Court emphasized that such injunctions involve serious consequences and therefore require a strong prima facie case and compelling circumstances.

Emerging Types: Dynamic Injunctions (in Digital/IP Context)

In response to digital piracy, Indian courts (particularly the Delhi High Court) have evolved dynamic injunctions (and advanced forms like Dynamic+ or superlative injunctions) to block rogue websites, mirror sites, and future infringing domains without repeated applications.

Recent Developments (2024–2025)

Courts have granted dynamic injunctions in cases involving live sports streaming, such as ICC events and the FIFA Club World Cup 2025, to allow real-time blocking of newly emerging infringing websites. In cases like Star India Pvt. Ltd. v. IPTV Smarter Pro (2025) and Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. v. Moviesmod.bet (2024), courts passed ex-parte orders to effectively protect copyright owners from constantly changing and repeat piracy websites.

Situations Where Injunctions Cannot Be Granted

Under Section 41 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963, injunctions cannot be granted, inter alia:

- To restrain judicial proceedings

- To prevent breach of a contract not specifically enforceable

- Where the plaintiff has no personal interest

- When equally efficacious relief can be obtained by other means (Section 41(h))

Cotton Corporation of India v. United Industrial Bank (1983) 4 SCC 625: In this case, the Supreme Court held that the prohibitions listed under Section 41 of the Specific Relief Act are mandatory. Courts cannot grant injunctions in situations expressly barred by this section, even if other equitable considerations appear to justify relief.

Conclusion

Injunctions are important tools of preventive justice in Indian law. Although courts have wide powers to grant injunctions, these powers are exercised carefully and are guided by basic principles such as the existence of a prima facie case, balance of convenience, and the likelihood of irreparable injury. Court decisions, from landmark cases like Dalpat Kumar to recent developments such as dynamic injunctions in digital piracy cases, show a balanced and practical approach. Courts aim to protect individual rights while also considering public interest and new challenges. With the rise of commercial, property, and digital disputes, injunctions continue to play a crucial role in the Indian legal system.