Introduction

Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) remain one of the most lethal and adaptable weapons used by insurgents, terrorists, and non-state armed groups across the world. From conflict zones in West Asia and Africa to insurgency-affected regions of South Asia, IEDs have evolved in form, concealment, and triggering mechanisms. Despite advancements in counter-IED (C-IED) strategies, detection remains a persistent challenge.

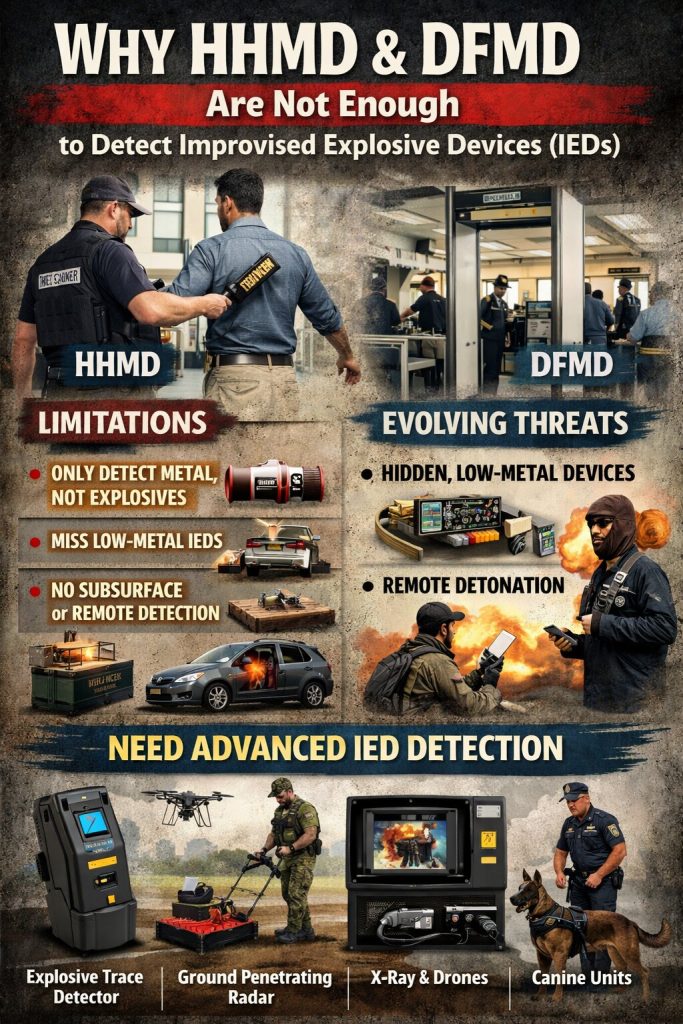

Hand-Held Metal Detectors (HHMDs) and Door-Frame Metal Detectors (DFMDs) are among the most commonly deployed detection tools at checkpoints, public venues, and security installations. While they are valuable components of layered security, reliance on HHMDs and DFMDs alone is insufficient and increasingly ineffective against modern IED threats.

This chapter critically examines the limitations of HHMDs and DFMDs, the changing nature of IED design, and the need for a multi-layered, intelligence-driven, and technology-integrated detection framework.

Understanding HHMD and DFMD

HHMDs and DFMDs function by detecting disturbances in electromagnetic fields caused by metallic objects. Their primary utility lies in identifying firearms, knives, and conventional metallic weapons.

Strengths include:

- Ease of deployment

- Low cost

- Minimal training requirements

- Quick screening capability

However, these advantages mask deeper structural weaknesses when applied to IED detection.

The Evolving Nature of IEDs

IEDs are not standardized weapons. Their strength lies in adaptability, innovation, and context-specific design.

- Declining Metal Content in IEDs

Modern IEDs increasingly use:

- Plastic casings

- Wooden containers

- Fertilizer-based explosives

- Low-metal detonators

- Carbon-based pressure plates

Such devices may contain little to no metal, rendering HHMDs and DFMDs ineffective.

- Non-Person-Borne IEDs

HHMDs and DFMDs are designed primarily for screening individuals, but a significant proportion of IEDs are:

- Roadside IEDs

- Vehicle-borne IEDs (VBIEDs)

- Under-floor or buried IEDs

- Wall-mounted or concealed devices

These threats lie outside the detection envelope of metal detectors.

Key Limitations of HHMD and DFMD in IED Detection

- Metal Detection ≠ Explosive Detection

HHMDs and DFMDs detect metal, not explosives. An IED can be fully functional without significant metal content. Conversely, benign metal objects (keys, belts, mobile phones) cause frequent alarms, leading to:

- Alarm fatigue

- Desensitization of security personnel

- Reduced operational vigilance

- Inability to Detect Triggering Mechanisms

IEDs may be triggered by:

- Chemical fuses

- Pressure plates

- Infrared beams

- Remote signals

- Timers made of plastic and silicon

Many such mechanisms escape metal-based detection.

- Limited Coverage Area

DFMDs are static and limited to specific choke points. HHMDs require close proximity and manual scanning, which:

- Slows throughput

- Increases human error

- Exposes personnel to blast risk

In high-footfall or conflict-prone areas, these constraints are operationally dangerous.

- No Subsurface or Stand-Off Capability

IEDs buried underground or concealed within structures cannot be detected by HHMDs or DFMDs. This is a critical shortcoming in counter-insurgency environments where:

- Roadside ambushes are common

- Pressure-plate IEDs dominate

Tactical Adaptation by Adversaries

Insurgent and terrorist groups continuously study security protocols. The predictable use of HHMDs and DFMDs allows adversaries to:

- Design low-metal or zero-metal IEDs

- Shift from person-borne to remote-detonated devices

- Exploit gaps in static security architecture

This asymmetric adaptation renders single-technology solutions obsolete.

Psychological and Operational Risks

- False Sense of Security

The visible presence of metal detectors creates security theatre, reassuring civilians while masking vulnerabilities. This false confidence:

- Reduces investment in advanced detection

- Encourages complacency

- Increased Risk to Security Personnel

Manual scanning with HHMDs places personnel within lethal blast radius if an IED is triggered. Numerous incidents globally demonstrate that first responders and search teams are primary victims of IED attacks.

Case Studies and Field Experience

Counter-IED experiences from regions affected by insurgency reveal that:

- Most successful IED interdictions result from intelligence leads, not metal detection

- HHMDs primarily intercept small arms, not explosives

- Sophisticated IEDs are often detected through behavioural analysis, technical surveillance, or accidental discovery

Training doctrines used by organizations such as NATO emphasize layered detection rather than single-sensor reliance.

Similarly, research and operational inputs from DRDO highlight the limitations of metal-centric detection in low-metal explosive environments.

What an Effective IED Detection System Requires

- Multi-Sensor Technology Integration

IED detection must combine:

- Explosive Trace Detectors (ETDs)

- Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR)

- X-ray imaging systems

- Chemical vapour sensors

- Canine detection units

Each tool compensates for the limitations of others. Despite the growing threat of IEDs, most districts and police commissionerates continue to operate without these essential detection and counter-IED systems.

- Intelligence-Led Operations

Human intelligence (HUMINT), signal intelligence (SIGINT), and community engagement are often decisive. Most IED plots are disrupted before deployment, not at checkpoints.

- Behavioral Detection and Profiling

Trained personnel observing:

- Nervous behavior

- Route reconnaissance

- Suspicious object placement

often outperform technology alone.

- Stand-Off Detection and Robotics

Robotic platforms and unmanned systems allow:

- Remote inspection

- Reduced human exposure

- Neutralization from safe distances

Policy and Institutional Gaps

Many security architectures prioritize visible deterrence over actual detection capability. Budgetary constraints and legacy procurement policies often favour HHMDs and DFMDs due to:

- Lower costs

- Ease of deployment

- Public reassurance value

However, this short-term logic undermines long-term security resilience.

Conclusion

HHMDs and DFMDs are necessary but not sufficient tools in the fight against IEDs. Their utility lies in detecting conventional metallic threats, not in countering the adaptive, low-metal, and remotely triggered IEDs that dominate modern conflict environments.

Over-reliance on these devices creates a dangerous illusion of security, exposes personnel to risk, and allows adversaries to exploit predictable detection patterns. Effective IED detection requires a holistic, layered, intelligence-driven approach that integrates technology, training, and community engagement.

In an era where IEDs continue to evolve faster than static defenses, security systems must move beyond metal detection and toward comprehensive threat detection. Anything less risks repeating the same failures—at a devastating human cost.